The ANC used to pride itself on being a "broad church", a place where people of different persuasions, convictions and orientations could come together and thrash out unity and compromise. But Ace Magashule's statement this week about the SA Reserve Bank shows that has changed, writes Pieter du Toit.

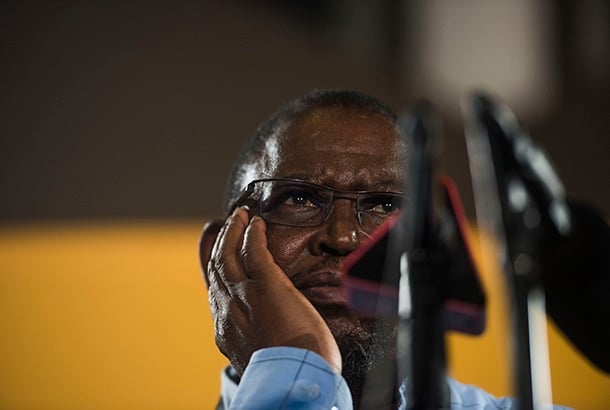

There was a grin on Enoch Godongwana's face when he sat on stage in the cold media centre at Nasrec in the south of Johannesburg during the ANC's policy conference in early July 2017, six months before the party's elective conference at the same venue.

Godongwana, facing the sharp glare of television spotlights, had been appointed as rapporteur of the economic transformation commission and went to the media centre to explain some of the policy proposals that were being forwarded to the elective conference. As chairperson of the economic transformation committee, a sub-structure of the party's all-powerful national executive committee, he is anything but a populist, and he helps direct the ANC's economic theories alongside the finance minister and the president. He understands the need for measured, responsible policymaking.

But as he started reading out his commission's decisions it seemed like he couldn't quite believe what he was doing. The ANC, he said, will start to formulate policy and implement plans to expropriate land without compensation. This might necessitate changes to the Constitution, Godongwana (every bit the unwilling participant as he is a loyal cadre of the party) told the gathered press pack in the icy hall.

And what's more, the party will also embark on a process to nationalise the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) because it remains an anomaly that the central bank has private shareholders.

It was clear that Godongwana, uncomfortable and periodically taking deep breaths, did not agree with his comrades' newest plans. When he finished his statement and took a series of questions, he decamped to outside the hall, where he made it clear what he thought of the plans. That he did not agree with it is to put it mildly.

But six months later, while the reformists managed to narrowly take the ANC's presidency and marginal control of the NEC, those exact policy proposals were adopted as official party positions. Efforts to defeat them came to naught and President Cyril Ramaphosa, although he has tried to eschew the sharper edges of expropriation without compensation as far as he could, is now bound to them.

It's that divide and unease among many reformists about policy that Ace Magashule, the ANC's secretary-general, sought to exploit this week when he announced on Tuesday that the party will seek to "expand" the SARB's mandate while investigating the implementation by the central bank of quantitative easing measures – printing money.

Magashule's statement wasn't about economic policy or about embarking on a considered debate on the SARB's role, it was belligerence and a purely political move to challenge Ramaphosa and signal that the resistance is only to get firmer from here on end.

As always, the tectonic plates inside the governing party split along economic lines. And access to resources. Magashule, and the Zuma-Gupta faction, know this.

The broad church

One of the ANC's defining characteristics has been its tradition as a so-called "broad church", an organisation that was a home for members of all ideological, racial, gender and other orientations and persuasions. The party was a home for those who believed in the free market and those who were convinced by an interventionist or socialist state. It became a political vehicle for black, white, Indian and coloured and it effected laws which gave gay marriages the same status as straight marriages, a first in Africa.

But that "broad church", the idea that the party can house both free marketeers and statists is increasingly under pressure, with policy uncertainty and ideological drift a hallmark of the ANC over the last decade.

When the party was unbanned in the 1990s the hegemonic slant was towards socialism, although it was tempered by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin wall. And although the ANC's socialism – which, according to Jeremy Cronin wasn't a Soviet Union-style socialism – was the prevailing ideology, leading party lights like Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma had already exited the South African Communist Party (SACP).

Between 1990 and 1994 the ANC started leaning towards neo-liberalism, and when the party took power in 1994 it also adopted many of the policies espoused by Bill Clinton's America and Tony Blair's New Labour. It culminated in the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) macro-economic strategy, rejected and vilified by the left as the "Class of 1996 Project".

Conflict and division about economic policy served as the backdrop to the assault on Mbeki's presidency and was used as pretext by the broad coalition of Zuma-ites, Cosatu, the SACP and the ANC Youth League to oust Mbeki.

It did lead to a change of tack, and GEAR was ditched in favour of a myriad of new policy frameworks, directives and directions, including the National Development Plan, the New Growth Path and many others. But gradually broad government policy – and specifically economic policy – was shunted aside as the state capture and rent seeking era broke after 2013.

With the country missing the great commodities boom and the effects of the economic crisis of 2008 lingering, South Africa's economy – growing steadily after 1994 thanks to, among other things, the post-apartheid dividend – started grinding to a halt. And the Zuma network, busy constructing a system of extraction and looting, was too busy to concern itself about policy development and direction.

The ANC's broad church, a place where ideas were contested, became a clearing house for patronage networks.

Magashule's ruse

Gordongwana was anything but mildly perturbed as he had been at Nasrec when Magashule, who presided over a "network of corruption", according to investigative journalist Pieter-Louis Myburgh, made his announcement about the SARB on Tuesday.

Magashule's account of events at the NEC meeting are simply not true, he said in a statement. Finance Minister Tito Mboweni reacted saying the SARB must be left alone. And the SARB's governor, Lesetja Kganyago, said there are "barbarians at the gate" of the central bank.

Two senior ANC leaders, one a member and one an immediate former member of the NEC, say it's clear that the Magashule faction – the anti-reformists – are under pressure, desperate and increasingly antagonistic. These statements (like Magashule's about the SARB) aren't motivated by policy development or responsible dialogue, but with more nefarious motives in mind.

Just like the "debate" in 2009 around the nationalisation of mines weren't done with the redistribution of wealth or justice for mining communities as driver, but rather about securing compensation for collapsed BEE deals and wanting the state to pick up the bill.

The secretary-general's statement about the SARB is a ruse. His comments were political, not economic.

The ANC used to characterise itself as a broad church of ideas. But it has now become a broad church of those seeking to uphold the rule of law, and those who want to dismantle it.

Policy – economic or otherwise – is a sideshow.