On May 23, the people of India delivered their verdict in electing members of Parliament, who would echo their voice in the Lok Sabha. In the biggest democratic exercise of the world, 613 million people, nearly twice the population of the US, exercised their franchise. It was the culmination of a prolonged and acrimonious election campaign, which is expected in a democracy of the scale and complexity of India. Yet, this time around, the political rhetoric dragged even the Election Commission into the battlefield. Players of the game sought to question not only the referee, but also the instruments and the rules of the game. Now that the exercise is over, it is perhaps germane to ponder over some key issues raised during this election.

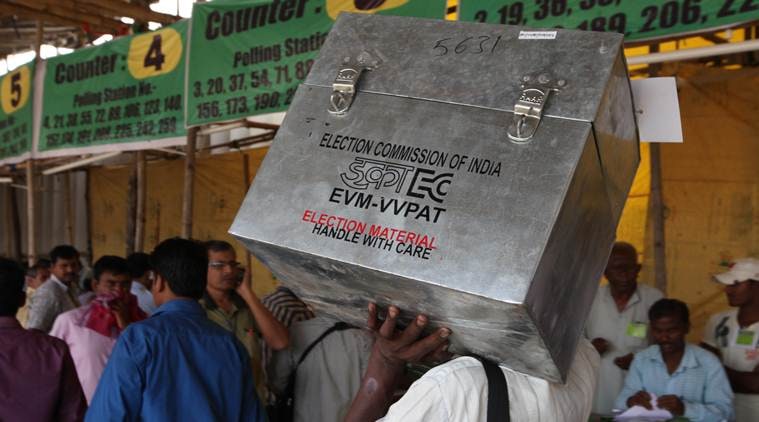

First, let us address the tool of elections — the Electronic Voting Machine (EVM). Aspersions were cast on its integrity, and by implication, on the whole election machinery. Some people even argued for a reversion to the paper ballot, jettisoning decades of reform in the conduct of elections. Questions were raised on the statistically correct sample of Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) machines to be counted for certainty of results. The matter went up to the Supreme Court, which ordered a mandatory count of five randomly selected VVPAT machines per assembly segment. In smaller states like Mizoram, it amounted to nearly a fifth of machines being validated. The results were astounding. In over 20,000 counts, there wasn’t even a single instance of mismatch between the EVM and VVPAT count. This wasn’t just an endorsement of the humble EVM, but also a tribute to the 12 million officials engaged in the conduct of elections. It should be a matter of pride for all Indians that no nation has taken a bold leap of faith in venturing into the use of such machines for elections at such a scale.

Second, let us look at the integrity of electoral rolls, which is the basis of entitlement for franchise. This time around, the EC intensified the use of technology for greater transparency. The ERONET is an integrated national electors database, armed with data analytic tools to throw up cases of data inconsistency, redundancy and duplication, which become red flags for the Electoral Registration Officers, requiring mandatory physical verifications. Acknowledging that there may still be room for error, the Commission passed on the onus of verification to the voters. A Voter Helpline app was launched, empowering all voters to apply online for registration. This was linked with a universal toll-free number (1950), which allowed voters to verify the entries in the rolls. A special emphasis was given to enroll physically challenged voters and a PwD (persons with disabilities) app was launched to enable people to mark themselves on electoral rolls. In order to ensure “accessible elections”, special arrangements were made across the country for voter facilitation, including provision of ramps at polling stations, training of polling parties in sign language, braille ballot papers etc. More than 6 million persons with disabilities (those who had marked themselves on the electoral rolls) cast their ballot across the country.

Last, the “Model Code of Conduct” and its enforcement by the EC. The Model Code draws upon the powers vested in the EC under Article 324 of the Constitution for “superintendence, direction and control” of elections to Parliament and legislature of every state. It lays down the guiding principles for conduct of political parties, especially the party in power, to ensure that there is a level-playing field during elections. However, for most part, since the code is issued by way of an executive order, only certain cases of violation invite action under the Representation of Peoples Act, 1951 and the Indian Penal Code. Perhaps, the debate around enforceability of the code could be a trigger for a wider discussion on according statutory backing to the code, with clearly defined penalties for violation.

However, during this election, as a step towards greater citizen empowerment, the “C-vigil” app was launched. Citizens could geotag pictures and report cases of violation on the portal, with assured action within 100 minutes of reporting. For the first time, there was a decentralisation of reporting, which saw thousands of cases being reported and redressed through this portal.

The degree and nature of electoral reforms will require wider debate and political consensus. The EC can be an enabler of this dialogue, which must embrace not only the processes required for ensuring greater fairness in the conduct of elections but also transparency in electoral funding, measures to curb the use of money power. In the meantime, let us not sully the reputation of institutions or question the hard work of millions of officials who work tirelessly for their national duty. For all the doubting Thomases, let us lean on the words of Charles Dickens: “Men who look on nature, and their fellow-men, and cry that all is dark and gloomy, are in the right; but the sombre colours are reflections from their own jaundiced eyes and hearts.”

The writer is an IAS officer. Views are personal