“I just looked at some data … out of all the ODI countries, the England pitches have got the least swing over the past 20 years or something. So bouncers — we’re going to have to use well. That’s a real wicket-taking ball.”

Pat Cummins

Before Australia’s World Cup opener against Afghanistan

Twenty years was perhaps an exaggeration, but Australia’s pace spearhead Pat Cummins was stating a perceptible trend. The limited-over pitches in England have long been defanged. There’s data validating his claims — in the last four years, the surfaces in the UK have offered the least movement, swing or seam. Cardiff has been the most conducive, but even there, the average degree of movement is .60, which doesn’t quite connote to a swinging beauty (the bowl then should be deviating around 1 to 1.10 degree). So, it’s no coincidence that Cardiff has been the only venue that has seen fuller-length deliveries.

But new-ball bowlers still commit the folly of striving for fuller-length balls, so that they could extract sideways movements, only to gift-wrap boundary balls. As had the Australian seamers during the whistle-stop limited-over series against England last year, where only Billy Stanlake conceded less than 6 runs an over (5.75). Australia ended up conceding 300-plus totals thrice (once almost 500, as England blasted 481). So has been the story of most limiter-over series games in the country, since the last World Cup.

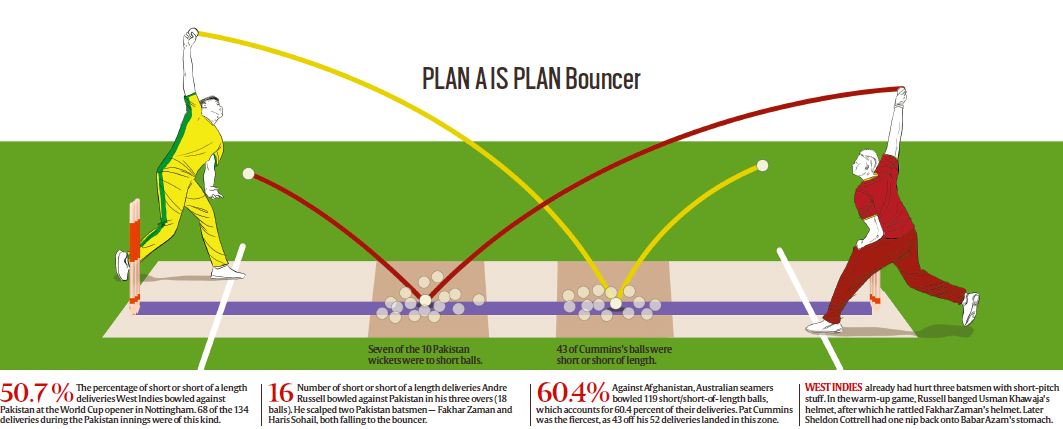

So when there isn’t swing, bounce becomes the deadliest weapon, at once testing the batsmen’s back-foot technique as well as bringing into play the two most risk-implied strokes in the game, pull and cut. Cummins himself walked the talk with a hostile first spell against Afghanistan wherein he made the ball leap awkwardly at them, from short as well as short-of-length areas. Needless to say the batsmen were fending to save their body from blows than getting their wickets battered. Short-pitch bowling, as a default weapon, thus stemmed from necessity.

***

“No one likes a ball, 140, 145km/h at your head, so that’s why the bouncer has been a favourite tactic thus far. But you can only bowl two an over and the other four need to be spot on.”

Carlos Brathwaite

After the Pakistan match

Pakistan batsmen would vouch for Brathwaite’s word. For 21.4 overs, they were made to endure vintage Carribean hostility—balls whizzing past their noses, blasting their helmets and rattling their torsos. Andre Russell struck Fakhar Zaman’s helmet and the ball trickled onto his stumps, while Sheldon Cottrell struck Babar Azam on his tummy. The Pakistan batsmen tried to weave and sway away from the line, but the Caribbean bowlers were relentlessly precise in targetting their bodies, often landing the ball a yard outside the off-stump and pinging it back into their bodies.

As pertinently, like Brathwaite implied, they neither over-did it nor followed up those brutish rip-snorters with boundary balls. If they were not bowling short, they kept it short-of-length, compressing the batsmen for both width and length, choking them for run and for once shredding their characteristic inconsistency. That seven of the 10 wickets were wrought with short or short-of-length deliveries captured the full story.

Moreover, they were so clear of their strategy that they dropped their most experienced bowler, Jerome Taylor, so that they could go full pelt with a quartet of fearsome hit-the-deck bowlers. Taylor, on the other hand, is more of a full-length probing medium-pacer. In a sense, they have unwittingly demonstrated the template to bowl on the excessively batting-friendly English conditions. An irony that talks of 500-plus totals have been blown away by the bouncers.

***

“With our pace and bounce, I feel like that [bumper] is a really good wicket-taking ball or a dot ball. It is going to be a risk if a batter is trying to play that every time.”

Pat Cummins

Before the West Indies match

If the West Indies believe that they can bounce out any side with their the battery of young pacers, so can the Australians, Cummins is certain. Besides Cummins, the most potent practitioner of the short-stuff, they have Mitchell Starc and Nathan Coulter-Nile besides reserves Jason Behrendorff and Kane Williamson, all capable of sustainted short-pitch cannonade. Among them, Starc is perhaps the only one who preys on the fullish length, what with his ability to bend the ball back into the right-hander. But even he alternated between the fullish and short-of-good length against Afghanistan.

This particular ability—to seam the ball into the right-hander—makes him deadlier, for batsmen can’t line up for just the short ball. He can’t just hang on the back-foot waiting for a short-ball. Several Afghanistan batsmen committed this mistake, and when the balls were pitched up they were no position to drive or flick. The short-ball danger kept swirling in their head, cluttering their judgment, and survival than run-scoring became their priority. Even trying to defend carries risk, and no delivery prompts the whether-to duck-under-or-play-it dilemma like the short ball.

Another reasoning is that the square boundaries being longer than straight ones in most of the English ground, the horizontal-batted shots do carry risks. The top-edges and aerial cuts could end up safely in the fielders palms. Trent Bridge fits the description perfectly.

***

“I’m not going to change anything, I’m going to be aggressive but be smart about it.”

Andre Russell

After the Pakistan match

The Australians might be the most proficient horizontal-bat purveyors around, but that wouldn’t deter the West Indies bowlers from tearing up their Plan A when they meet the world champions on Thursday. If any, Russell says they will only ratchet up the tempo. Fluent though the Australians might be in unleashing the cut and pull, but aggressive short-pitch bowling can harass the best of them. They needn’t look beyond Jofra Archer cutting the Proteas batsmen into halves in the opening match. Or in the practice match, when Andre Russell struck Usman Khawaja on the helmet with a nasty bouncer.

It’s not just plain hope but the conviction in their collective ability. All of them—Cottrell, Russell and Oshane Thomas—can clock around 90mph, are sharp, on-their-face and explosive. Pace is a crucial ingredient, as bounce without speed doesn’t drill a visceral fear into the batsmen. For instance, teams like Sri Lanka, Afghanistan or Bangladesh couldn’t be as effective with the short ball as the West Indies, Australia, or England’s Jofra Archer. And they do it smartly.

Not once did the bouncer drift down the legs or bang high over the batsman’s head. Often the interception point was just below the batsman’s chest, that blindspot.