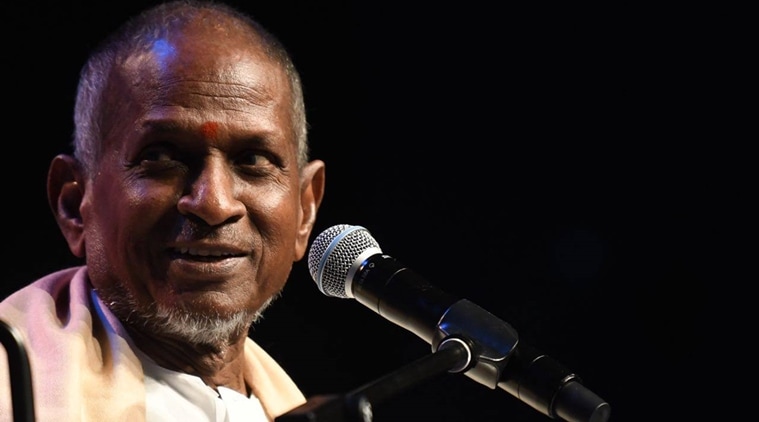

Music maestro Ilaiyaraaja has been very protective about his work. When he sued SP Balasubrahmanyam over royalty issues, the industry was divided on the matter. But one could see a point in Ilaiyaraaja’s concerns about others making a fortune off his creations without giving him his rightful share. His latest outburst, however, is slightly on the harsher side. In a recent interview, Ilaiyaraaja took exception to the usage of his classic songs in last year’s hit romantic drama 96. While describing the practice as “very wrong”, he said it showed the “impotence” of the composers to come up with something as good as his 80s songs.

I think this topic alone warrants another 30 minutes of discussion with Ilaiyaraaja to clearly understand his stance on the subject matter. Were his comments poorly worded? Of course, yes. But, at the same time, I believe he was overzealous while making a statement.

By his own admission, Ilaiyaraaja has not seen 96. Let’s assume that he was oblivious to the extent and the method in which his old classic songs were used to enhance the nostalgic theme of the movie. Say, he was also unaware that filmmakers of 96 had followed all due procedures to use the songs. And still, Ilaiyaraaja’s argument holds against using already established popular songs in a film’s soundtrack to strike an immediate connection with the audience.

Of late, Hollywood filmmakers have been accused of becoming lazy by heavily depending on retro to make up for their incompetent writing. Suicide Squad, for example, was criticized for overusing preexisting soundtracks to emphasise something very obvious. You hear vintage “Spirit in the Sky” in the backdrop when Suicide Squad is flown into the city. The song is played for a very banal reason to say the Suicide Squad in the sky.

Sample this: In the entire run time of Race 3, the theme music of Race franchise is the only thing that means something for the audience. It is because the music has a recall value to something far better in the past. Here the specific music is not used to convey some deeper meaning or growing conflict in the narration. Instead, it is used to evoke a sense of nostalgia so the audience could tolerate a tiresome narration.

Take the example of the bar scene in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, we see Terminator for the first time in his full leather costume to “Bad to the Bone” playing in the backdrop. We now know that he is “bad to the bone” but we are yet to find out whether he is the villain of the film. The practice of embedding pop culture hits in mainstream films to play up the nuances of specific scenes have been in practice for many years now in Hollywood. And this narrative technique is colloquially referred to as “needle drops.”

Acclaimed filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino are considered masters of “needle-drops” for their clever use of pop culture songs in their films.

In India, however, we don’t get to see a lot of needle drop films. In recent time, we had two Tamil films, 96 and Super Deluxe which extensively used this technique in an effective way. Before we dwell on the subject, just let’s also look at a few examples of needle drops in Tamil cinema.

Needle drops could be used for various reasons in the film: to highlight the period of the film, underline irony, comedy, or other terrifying emotions and growing conflict. It was while watching Subramaniapuram (2008), the first time I realized the impact of using old songs in modern Tamil films.

The scene is set at the regular hangout place of the protagonists, Azhagar (Jai) and Paraman (M. Sasikumar). Azhagar promises Paraman that he will prove to him that their boss’ daughter Thulasi (Swathi) is interested in him romantically. As she passes by them, “Siru Ponmani” song from Kallukkul Eeram (1980) plays on the radio as Azhagar and Thulasi exchange romantic glances. The old Ilaiyaraaja song complements the scene in two ways. One, it establishes the period of the film, which is set in the 1980s Madurai. Two, it fits the scene so flawlessly, while kindling the old memories of the audience.

Another great service of the film is it helped Ilaiyaraaja’s old song stay fresh in the memory of the young audience. If not for this song, the chances of me typing “Siru Ponmani” in the search bar of my music app would have been slim to none.

The retro songs also help the filmmakers to achieve a higher degree of humor or as simple as put a smile on the face of the viewers. You can’t help but smile when Karthi in Paruthiveeran (2007) glams up a bit while “Kaadhalin Deepam Ondru” (another Ilaiyaraaja classic) is playing on the radio. You can’t say you didn’t laugh when Shiva slips into a duet number of “Poththi Vachcha” (Ilaiyaraaja, again) originally from Mann Vasanai (1983) when he sees his love interest in Chennai 600028, which was directed by Ilaiyaraaja’s nephew Venkat Prabhu. And Ilaiyaraaja’s son Yuvan Shankar Raja had scored for the film.

C. Prem Kumar’s 96 and Thiagarajan Kumararaja’s Super Deluxe, however, doubled down on Ilaiyaraaja needle drops. Not like director Todd Phillips of War Dogs but in a way that would be favoured by Quentin Tarantino.

Composer Govind Vasantha scored a terrific original soundscape that matched the film’s meditating theme of nostalgia. And the director-composer’s collections of curated vintage songs only made certain scenes more appealing than they already were. Didn’t you find young Janu adorable when she sang “Chinna Ponnu” from Aayusu Nooru (music by T. Rajendar) to keep her classmates from indulging in jibber-jabber? Or every time she handpicked a song to send a message to her school crush?

An original score may not have achieved what “Evarum Sollamale” did when the grown-up Janu sings it at the school reunion. It serves like a dog-whistle sending a coded message about her emotional state to only to some among the crowd. So is “Yamunai Aatrile” which brings out Radha’s, in this case Janu’s, predicament, longing and pain over her love interest.

We can write a sperate essay on the curation of Thiagarajan Kumararaja and Yuvan Shankar Raja for Super Deluxe. Each needle drop brings out irony, comedy, and thoughts of the characters in specific scenes. For example, Mugil is listening to “Ennadi Meenatchi” (a song about betrayal) while he walks up the stairs to his house when his wife Vaembu struggles to hide the dead body of her lover. Isn’t it ironic when you see Shilpa drape the saree and wear makeup with sultry “Maasi Maasam Alana Ponnu” playing in the backdrop?

Unlike the west, the Tamil filmmakers employ needle drops to pay ode to the classic work of their predecessor as opposed to make up for a lazy storytelling technique. Films like 96 have given us beautiful original songs to cherish (like “Kaathalae Kaathalae”) in addition to refreshing our memories about forgotten old songs. And that needs to be encouraged.