Upheaval

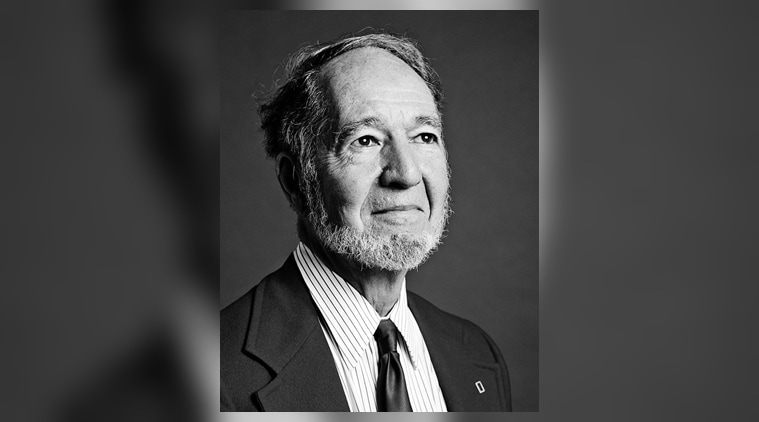

Jared Diamond

Allen Lane

512 pages

Rs 799

Jared Diamond, physiologist and professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles has written his seventh book as an exercise in extrapolation. In Upheaval: How Nations Cope with Crisis and Change, he draws his source material from his personal experience of six countries — the US, Germany, Finland, Chile, Japan, Indonesia and Australia. This is not a formally ordered database, and it is not a random sampling, either, since where an American researcher with specific interests is likely to work constitutes a fairly limited set. But Diamond’s approach is intuitive, and he says that the book is the “first step towards a formal study”, which would move forward from narrative to quantitative analysis.

His intuitive exploration is based on the premise that the manner in which individuals and collectives like nations respond to crisis is somewhat similar, though he readily agrees that they are not identical. His starting point is the checklist that crisis therapists recommend to individual patients: “Acknowledgement that one is in crisis, acceptance of one’s personal responsibility to do something, deploying individual core values,” and so on. Extrapolated to nations, these actionable bullet points become: “National consensus that one’s nation is in crisis, acceptance of national responsibility, national core values,” and so on. For seven of the 12 points on the checklist, “the parallels are straightforward.”

None of the six nations which feature in Upheaval are located in South Asia. However, India and Pakistan do make cameo appearances no less compelling than Hitchcock’s. Diamond writes of a hypothetical scenario in which India retaliates against a terrorist attack by invading Pakistani territory. Islamabad uses a tactical nuclear weapon against the invading troops, on the assumption that a limited nuke would not lead to escalation, but misunderstandings follow and escalation to all-out nuclear war becomes inevitable. Diamond expects that an incident of this nature will occur within the next 20 years, and it only remains to be seen if the regional powers manage to back off, as the US and USSR managed to do at the end of the Cuban missile crisis. (This scenario was written before Pulwama and Balakot, of course.)

“That’s the nuclear risk,” he said in the conversation with Indian Express. “For us Americans, an incident involving the USSR has always appeared to be possible — though it’s much less likely now. With Israel, it would be Iran, and there is the India-Pakistan flashpoint, of course. The challenge is the minimisation of risk, and the most important factor would be honest self-appraisal by both parties. In the hypothetical example, if Pakistan thought that it could use a tactical weapon against Indian troops without consequences, it would be deluding itself. And India could not afford to imagine that it could use a nuclear weapon near the border without the danger of escalation. Other negative factors influencing action would be victimhood and the denial of responsibility for one’s actions.”

In the Pulitzer Prize-winning Guns, Germs and Steel, Diamond had written of “the Anna Karenina principle”, by which nations which win the game of history tend to be favoured with similar advantages, but the losers have uniquely crippling disadvantages. Is Anna Karenina at play in this book, too, or can nations deal effectively with crisis by serendipitously hitting some of the right buttons? “Not sure if the right conclusions can always be reached,” said Diamond. “The most reliable way is to learn from history and accept responsibility.”

The 12-point checklist for dealing with crisis is also placed in an ideal world, where leaders are adequately informed and the populace is not disinformed. But politics is conducted in imperfect circumstances, and crises can build up slowly or spill over suddenly. An example of the first case is that of gunboat diplomat Matthew C Perry, who opened up Japanese ports for American trade by force in 1852-53. The Japanese response was to slowly open up to Western models of education, which have given their nation a literacy level of 99 per cent. But where the response is immediate — if the Japanese had chosen to fight Perry, for instance — decisions are often taken in the midst of information asymmetry, or even disinformation.

Does the leadership make a difference, as Carlyle’s Great Man theory suggests, or are events controlled by the tides of history? It is one of the fundamental points of debate in history, and Diamond votes against time-honoured wisdom. “The leader doesn’t always make a difference,” he says. Clement Atlee won a landslide victory for Labour in the 1945 elections in the UK, and used the mandate to institute Keynesian policies and a durable welfare system. “But had he not been there,” points out Diamond, “one of his people would have implemented the very same policies. Look at the present — all parties in the UK are equally short-sighted, and Brexit has become a crisis.”

Two items available to individuals in crisis are not entirely accommodated on Diamond’s checklist. One, while individuals have the option of seeking therapy, nations can only seek financial aid, and it doesn’t really work. “The Bretton Woods formula is a cruel joke,” he says, “because all nations cannot possibly be sustained at the consumption levels of the prosperous nations. However, more equal consumption can be achieved by curtailing waste. In the US, this is resisted on the ground that it would lower its standard of living. That isn’t true, though, because Europe has a higher standard of living than the US with lower consumption. We don’t have to sacrifice your standard of living, only reduce our consumption.”

The fate of individuals in the most extreme crisis is for the neighbours to call the police on them. Nations also have the option of inviting the attention of the globocop, but Diamond is sceptical about its effectiveness: “Recent US attempts at policing have not been happy — Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, and we supported change in Libya. None of them have been able to install a happier government. On the other hand, there have been happier interventions, like the deposition of Idi Amin in Uganda in 1979. There’s also the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971, in which India played a crucial role.”

When he planned this book six years ago, Diamond had wished to include businesses and internet communities, besides nation states. In fact, the forces of globalisation have created several categories of groupings which do not respect national borders, but have taken on some of the attributes of nations. Multinational corporations have footprints far bigger than national territories, and yet retain financial and structural integrity. Diasporas like India’s are large enough to influence opinion back home. Multilateral bodies aggregate nations, and the European Union, while chronically in trouble for a decade, since the sovereign debt crisis in Greece in 2009, is nevertheless a super-nation with its own parliament, central bank and apex court. The US and allies have been engaged in a war for territory with Islamic State, which ironically underscores its pretension to statehood. And internet communities like Facebook have taken the first step on Diamond’s checklist for crisis mitigation — they acknowledge that there is a crisis.

There should be much to probe when Diamond moves to formalise his narrative into quantifiables, including entities and collectives which have been excluded from Upheaval. “It’s 498 pages long already. No one would ever buy it if I’d extended it. Be grateful that I didn’t,” he said.