Dharti kahe pukaar ke, geet bichha le pyar ke

Mausam beeta jaaye, mausam beeta jaaye

Apni kahani chhod ja, kuch toh nishaani chhod ja

Mausam beeta jaaye…

This sublime and evocative ditty from Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen (1953), the story of a farmer trying to save his two acres of land, is also the leitmotif for the opening scene of the recent Netflix series, Sacred Games. Someone throws a dog from the topmost floor of a building along the dialogue ‘Bhagwan ko maante ho?’ The dog falls and dies. Salil Chaudhry’s simple yet inventive, “folkish composition with the rigour of a classical song”, rendered by playback singer Manna Dey, enters the frame like a person and hangs in there. Writer Varun Grover wanted only this piece to be where it is. “We wanted to use the song as the protagonist’s (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) last call before his suicide. In my opinion, this is the most haunting song of that era. Dey’s rendition adds that level of seriousness the theme requires while retaining the folk ballad of the soul,” says Grover.

A unique voice and singing style, the genius of Dey occupies a distant place not just in the annals of Indian cinema, but also in the world of Indian classical music. Dey, who would have turned 100 this month, gave us a repertoire so varied that at times it was difficult to understand as to how someone was able to understand and deliver the range between a soul-stirring Puchho na kaise maine rain bitayi (Meri Surat Teri Aankhen, 1963) in the sonorous morning raga raag Ahir Bhairav, to RD Burman’s spunky Aao twist kare (Bhut Bangla, 1965). There is the iconic musical dual (with Kishore Kumar) Ek chatur naar (Padosan, 1968), the delicate Tu pyar ka sagar hai (Seema, 1955), heart-wrenching Aye mere pyare watan (Kabuliwala, 1961), the sensuous Pyar huya iqrar huya (Shri 420, 1955) and the significant Zindagi kaisi hai paheli haaye (Anand, 1971), which remains a soundtrack to our lives. It was a film career that spanned more than half a century, 4,000 songs and delivered classics that were adored by the masses and ardent connoisseurs alike.

Born as Probodh Chandra Dey in Kolkata in an academic and culturally aware family, Dey was the nephew of Bengali composer and director KC Dey. “If it wasn’t for the influence of my uncle and mentor, I would have ended up as a barrister, which my chartered accountant father wanted me to become. Academics was a priority in my home. So till I was not done with college, I was not really allowed to get into a field that was unpredictable,” Dey had told this journalist post the announcement of a Dadasaheb Phalke award for him in 2009.

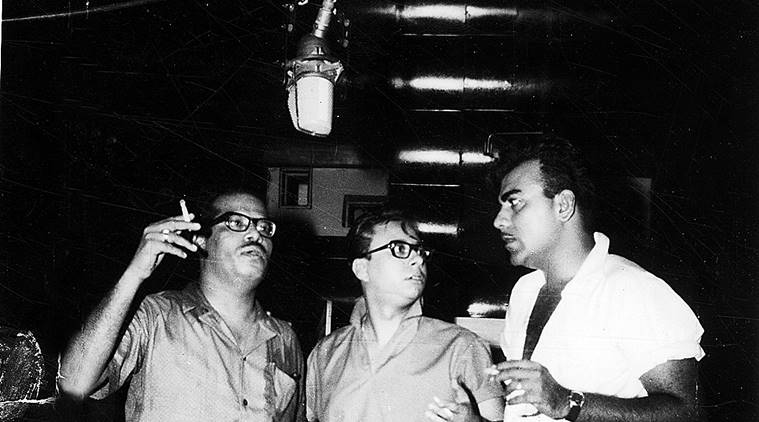

He came to Mumbai to assist his uncle first and later, SD Burman. This is when he began taking classical music lessons from Patiala gharana scions Ustad Amanat Ali Khan and Ustad Abdul Rahman Khan. His playback singing career began with SD Burman’s Tamanna in 1942. A duet with Suraiya, Jaago aayee usha found quite some attention from those cocking their ears to 72RPMs at the time. He sang a slew of songs before hitting bulls eye with Kavi Pradeep’s Upar gagan vishal (Mashal, 1950). This was followed by a long association with composer duo Shankar Jaikishen and Raj Kapoor in Shree 420, Chori Chori, Mera Naam Joker, Parvarish, Dil Hi To Hai and Awara, among others.

“He began singing in an era where the actors used to sing their own songs. So playback singers needed to have very large, big voices. But I think Manna da was the only one who didn’t have a conventional hero’s voice. He was there on the basis of sheer talent and expressiveness of his voice,” says lyricist and singer Swanand Kirkire, who has distinct memory of Aao sawariya from Padosan, “It’s supreme musically and also has that naughty streak. The balance is immaculate,” he adds. “Pancham always convinced me,” Dey had said.

But what made Dey exceptional in the Mohammad Rafi and Kishore Kumar era was his distinct classical voice. There was Laaga chunri mein daag, which is dreaded by male singers even today and the famed musical dual Ketki gulab juhi (Basant Bahar, 1956) with Pt Bhimsen Joshi. Joshi’s voice is used for the court musician who eventually loses the contest to Bharat Bhushan’s character. Dey had sung for Bharat Bhushan, and was reluctant for many days. “I should sing with Bhimsen Joshi, compete with him, and defeat him too? I can’t do this,” he said in the Films Division documentary on Joshi, directed by Gulzar. Joshi convinced him eventually.

“As a young boy learning classical music in the ’70s, I’d listen to Puchho na kaise and other classical songs by Manna da, and sing them in my riyaaz. He understood the bhaav of a raga so beautifully. His singing was refined singing at its best,” says prominent classical vocalist Sanjeev Abhyankar. But Dey wasn’t so happy with his delivery of Puchho na, despite composer SD Burman’s convincing nod. “I could have done better with a few more takes,” he’d said.

Apart from a long and successful Bollywood career, Dey also sang a number of Bengali songs — in Satyajit Ray’s Jalsaghar, Antony Firingee and a slew of songs for Uttam Kumar. Most Bengalis can’t forget the popular pop icon Coffee houser sei adda which makes regular appearance in puja pandals and on reality shows. “He touched a chord with the heart. It was hard to part with that voice in that moment,” says Abhyankar.

Rafi had once said, “You listen to my songs. I listen only to Manna Dey.” The generations of singers coming after Rafi are likely to feel the same.