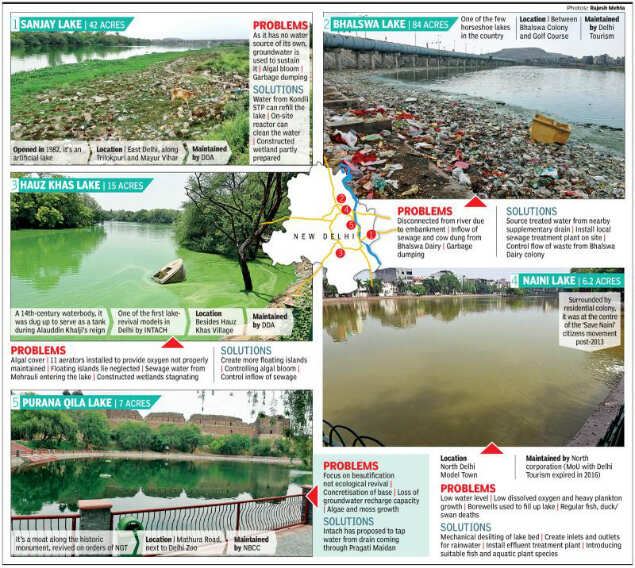

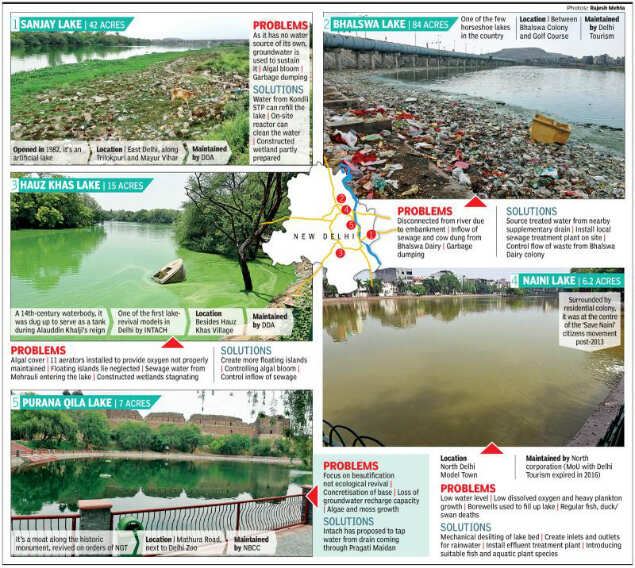

At a time when the Delhi government is planning to spend hundreds of crores to revive more than 200 waterbodies, the city’s existing lakes — some as large as the Nainital lake — are dying a slow death. Paras Singh and Jasjeev Gandhiok profile their plight.

Naini Lake: Model Town’s little lake is on life support. Turn off the three municipal borewells that steadily pump water into it, and it might turn into a dry bowl. The groundwater keeping it alive is a cure worse than the disease — experts say it is making the lake salty and unlivable for aquatic plants and animals.

The lake looked uninviting when TOI saw it last week. The water was muddy and rich with plankton, the air rank with decay. “It smells, and as summer peaks, more fish will die,” said Juhi Chaudhary from the ‘Save Naini Lake’ campaign that has been fighting for the lake’s revival since 2015. She said nothing has been done about the algae in the lake, nor about improving the water quality and enriching its biodiversity.

This is despite the attention the lake gets. Politicians have visited it and made assurances about reviving it. Bureaucrats have released plans for public consultation. But the lake changes only for the worse. TOI found the surrounding walks and benches broken. A waterfall didn’t work. Some trees planted along the boundary had been uprooted. One corner was infested with rats.

Boating used to be one of the lake’s attractions, especially for DU students, but a tussle between the AAP-led tourism department and the BJP-led North Delhi Municipal Corporation put an end to it about three years ago, said corporation officials. Most of the ducks and swans have also died.

Can it be saved? C R Babu, an ecologist working on the revival of several waterbodies in Delhi, said the lake is spring-fed and it will revive naturally if its bed is de-silted and storm water used to augment its fresh water supply. The water in the lake will need to be cleaned up and aerated with aeration fountains and jets. Growing water-cleaning fish and aquatic plants will also help.

But municipal officials say they don’t have the funds to take up these works. Their master plan for the lake has been in limbo for a year due to shortage of funds. Chaudhary disagreed: “The problem is of intent and vested interests. They had the funds. The Centre announced the funding, but nobody knows where the funds went, if they were sanctioned.”

Bhalswa Lake: The last time this lake beside Bhalswa golf course filled up to the brim was in 1964. That year, an embankment cut off the inflow of water from the Yamuna. Then, a landfill swallowed one arm of its horseshoe shape, reducing it to a half-kilometre-long pond. Finally, human and animal excrement from nearby settlements fouled up its waters so badly that Bhalswa Lake — once comparable in size to the lake in Nainital — is now a sorry sight.

Last week, TOI saw sewage from punctured drains around Bhalswa dairies flowing directly into the lake’s western bank. So much waste has been dumped into it that islands of mud and garbage take up half of its width along Outer Ring Road. Yet, Delhi government, somehow, still imagines it is a site for adventure sports like kayaking.

Even the eastern bank, where DTIIDC offers boating, is lined with garbage and leftovers from Chhath Puja. Manu Bhatnagar, principal director of conservation body Intach’s natural heritage division, said, “In summer, the water level goes down so much that you cannot even boat in it.”

Can it be saved? Bhatnagar said aquatic life in the lake will revive if dumping of waste from the dairies stops. Intach had recommended building a sewage treatment plant for the dairy drains, and using treated water from the nearby supplementary drain to recharge the lake. Its management plan for the lake lies forgotten. A recent joint survey by DDA, PWD and Delhi Jal Board has not translated into action either.

North corporation’s proposed biogas plant for the dairies might save the lake, though. The corporation will buy animal dung from the dairies and use it to generate electricity from biogas.

Purana Qila Lake: The lake outside Purana Qila was once part of a moat that kept enemies at bay. Now, after a Rs 30-crore make-over last year, it stops water from seeping into the soil.

As Delhi’s groundwater level has plunged, open grounds and waterbodies are needed to recharge it. Yet, the lake bed has been lined with an impervious geo-textile disregarding objections from environmentalists. Ironically, the renovation was done under orders from the National Green Tribunal, the country’s top environment court.

Skirting the fort’s 500-year-old walls between Talaqi (forbidden) and Humayun gates, the renovated lake is no better than a tar road. Bhatnagar said it is now dependent on tankers and other artificial sources because a lot of water is lost to evaporation.

The lake could have been restored without making it less useful to the environment, Bhatnagar said. Intach had recommended using water from the NDMC drain that crosses Bhairon Marg near the fort. “You would not have needed to concretise the lake. This would have been a much cheaper option too.”

Left to nature, it might have been easier to maintain as well. Although the lake was inaugurated only last October, TOI found algae and moss spreading in its stagnant water.

Sanjay Lake: At first glance, the green waters of Sanjay Lake look like a thriving ecosystem with trees and resident birds. All is not well, though, as this 17-hectare waterbody — about as large as 24 football fields — in east Delhi’s Trilokpuri is dependent on groundwater.

“A lake needs to sustain itself naturally and not deplete groundwater,” said Bhatnagar. The conservation body had recommended feeding the lake from the Kondli sewage treatment plant. To keep the water moving, it had proposed to supply the lake water to the bus terminus and railway station at Anand Vihar for non-drinking purposes. “This would not only ensure the water keeps moving but also generate revenue,” said Bhatnagar. But their proposal remains on paper.

With adventure activities on offer, the DDA-maintained lake is a popular family hangout. However, TOI found sections of the boundary wall broken and garbage dumped on the periphery.

Locals said large quantities of sewage flow into the lake, and the dense growth of algae and plants on the water — due to a high concentration of nitrates and phosphates from sewage — seemed to confirm this.

-: The ‘hauz’ in Hauz Khas has been around for 700-odd years, and for long it was Delhi’s model for reviving dead waterbodies. Not anymore. Today, you can smell the lake before you see it. Near the banks, its water is thick as slime and dark green with algae. Bhatnagar said the stench arises from the algal bloom that thrives on sewage entering the lake from Mehrauli.

Earlier, water from sewage treatment plants was further cleaned with duckweed near Sanjay Van, before being released into the lake, he said. “This is not happening anymore, and it significantly alters the quality of water entering the lake. Worse, sewage from the Mehrauli side is also entering the lake now.”

The lake’s old aerators don’t work and its 10 floating islands that purify water by sucking out nitrates are too few to make a difference. “While 11 aerators were installed for improved oxygen levels, poor maintenance means they are not functioning anymore,” said Bhatnagar. “The lake’s deep end, which is next to the buildings, falls in the shadow area and is the worst affected.”

Naini Lake: Model Town’s little lake is on life support. Turn off the three municipal borewells that steadily pump water into it, and it might turn into a dry bowl. The groundwater keeping it alive is a cure worse than the disease — experts say it is making the lake salty and unlivable for aquatic plants and animals.

The lake looked uninviting when TOI saw it last week. The water was muddy and rich with plankton, the air rank with decay. “It smells, and as summer peaks, more fish will die,” said Juhi Chaudhary from the ‘Save Naini Lake’ campaign that has been fighting for the lake’s revival since 2015. She said nothing has been done about the algae in the lake, nor about improving the water quality and enriching its biodiversity.

This is despite the attention the lake gets. Politicians have visited it and made assurances about reviving it. Bureaucrats have released plans for public consultation. But the lake changes only for the worse. TOI found the surrounding walks and benches broken. A waterfall didn’t work. Some trees planted along the boundary had been uprooted. One corner was infested with rats.

Boating used to be one of the lake’s attractions, especially for DU students, but a tussle between the AAP-led tourism department and the BJP-led North Delhi Municipal Corporation put an end to it about three years ago, said corporation officials. Most of the ducks and swans have also died.

Can it be saved? C R Babu, an ecologist working on the revival of several waterbodies in Delhi, said the lake is spring-fed and it will revive naturally if its bed is de-silted and storm water used to augment its fresh water supply. The water in the lake will need to be cleaned up and aerated with aeration fountains and jets. Growing water-cleaning fish and aquatic plants will also help.

But municipal officials say they don’t have the funds to take up these works. Their master plan for the lake has been in limbo for a year due to shortage of funds. Chaudhary disagreed: “The problem is of intent and vested interests. They had the funds. The Centre announced the funding, but nobody knows where the funds went, if they were sanctioned.”

Bhalswa Lake: The last time this lake beside Bhalswa golf course filled up to the brim was in 1964. That year, an embankment cut off the inflow of water from the Yamuna. Then, a landfill swallowed one arm of its horseshoe shape, reducing it to a half-kilometre-long pond. Finally, human and animal excrement from nearby settlements fouled up its waters so badly that Bhalswa Lake — once comparable in size to the lake in Nainital — is now a sorry sight.

Last week, TOI saw sewage from punctured drains around Bhalswa dairies flowing directly into the lake’s western bank. So much waste has been dumped into it that islands of mud and garbage take up half of its width along Outer Ring Road. Yet, Delhi government, somehow, still imagines it is a site for adventure sports like kayaking.

Even the eastern bank, where DTIIDC offers boating, is lined with garbage and leftovers from Chhath Puja. Manu Bhatnagar, principal director of conservation body Intach’s natural heritage division, said, “In summer, the water level goes down so much that you cannot even boat in it.”

Can it be saved? Bhatnagar said aquatic life in the lake will revive if dumping of waste from the dairies stops. Intach had recommended building a sewage treatment plant for the dairy drains, and using treated water from the nearby supplementary drain to recharge the lake. Its management plan for the lake lies forgotten. A recent joint survey by DDA, PWD and Delhi Jal Board has not translated into action either.

North corporation’s proposed biogas plant for the dairies might save the lake, though. The corporation will buy animal dung from the dairies and use it to generate electricity from biogas.

Purana Qila Lake: The lake outside Purana Qila was once part of a moat that kept enemies at bay. Now, after a Rs 30-crore make-over last year, it stops water from seeping into the soil.

As Delhi’s groundwater level has plunged, open grounds and waterbodies are needed to recharge it. Yet, the lake bed has been lined with an impervious geo-textile disregarding objections from environmentalists. Ironically, the renovation was done under orders from the National Green Tribunal, the country’s top environment court.

Skirting the fort’s 500-year-old walls between Talaqi (forbidden) and Humayun gates, the renovated lake is no better than a tar road. Bhatnagar said it is now dependent on tankers and other artificial sources because a lot of water is lost to evaporation.

The lake could have been restored without making it less useful to the environment, Bhatnagar said. Intach had recommended using water from the NDMC drain that crosses Bhairon Marg near the fort. “You would not have needed to concretise the lake. This would have been a much cheaper option too.”

Left to nature, it might have been easier to maintain as well. Although the lake was inaugurated only last October, TOI found algae and moss spreading in its stagnant water.

Sanjay Lake: At first glance, the green waters of Sanjay Lake look like a thriving ecosystem with trees and resident birds. All is not well, though, as this 17-hectare waterbody — about as large as 24 football fields — in east Delhi’s Trilokpuri is dependent on groundwater.

“A lake needs to sustain itself naturally and not deplete groundwater,” said Bhatnagar. The conservation body had recommended feeding the lake from the Kondli sewage treatment plant. To keep the water moving, it had proposed to supply the lake water to the bus terminus and railway station at Anand Vihar for non-drinking purposes. “This would not only ensure the water keeps moving but also generate revenue,” said Bhatnagar. But their proposal remains on paper.

With adventure activities on offer, the DDA-maintained lake is a popular family hangout. However, TOI found sections of the boundary wall broken and garbage dumped on the periphery.

Locals said large quantities of sewage flow into the lake, and the dense growth of algae and plants on the water — due to a high concentration of nitrates and phosphates from sewage — seemed to confirm this.

-: The ‘hauz’ in Hauz Khas has been around for 700-odd years, and for long it was Delhi’s model for reviving dead waterbodies. Not anymore. Today, you can smell the lake before you see it. Near the banks, its water is thick as slime and dark green with algae. Bhatnagar said the stench arises from the algal bloom that thrives on sewage entering the lake from Mehrauli.

Earlier, water from sewage treatment plants was further cleaned with duckweed near Sanjay Van, before being released into the lake, he said. “This is not happening anymore, and it significantly alters the quality of water entering the lake. Worse, sewage from the Mehrauli side is also entering the lake now.”

The lake’s old aerators don’t work and its 10 floating islands that purify water by sucking out nitrates are too few to make a difference. “While 11 aerators were installed for improved oxygen levels, poor maintenance means they are not functioning anymore,” said Bhatnagar. “The lake’s deep end, which is next to the buildings, falls in the shadow area and is the worst affected.”

#ElectionsWithTimes

Quick Links

Lok Sabha Election Schedule 2019Lok Sabha Election NewsDelhi Capitals teamMI team 2019Rajasthan Royals 2019RCB team 2019Maharashtra Lok Sabha ConstituenciesBJP Candidate ListBJP List 2019 TamilnaduShiv Sena List 2019AP BJP List 2019Mamata BanerjeeBJP List 2019 MaharashtraPriyanka GandhiBJP List 2019 KarnatakaAMMK Candidate List 2019BJP List 2019 WBLok Sabha Elections in Tamil NaduBSP List 2019 UPNews in TamilLok Sabha Poll 2019Satta Matka 2018PM ModiMahagathbandhanNagpur BJP Candidate ListChandrababu NaiduTamil Nadu ElectionsUrmila MatondkarNews in TeluguMadras High CourtTejashwi YadavArvind KejriwalTejasvi SuryaPawan KalyanArvind KejriwalYogi AdityanathJaya PradaSatta King 2019Srinagar encounter

Get the app