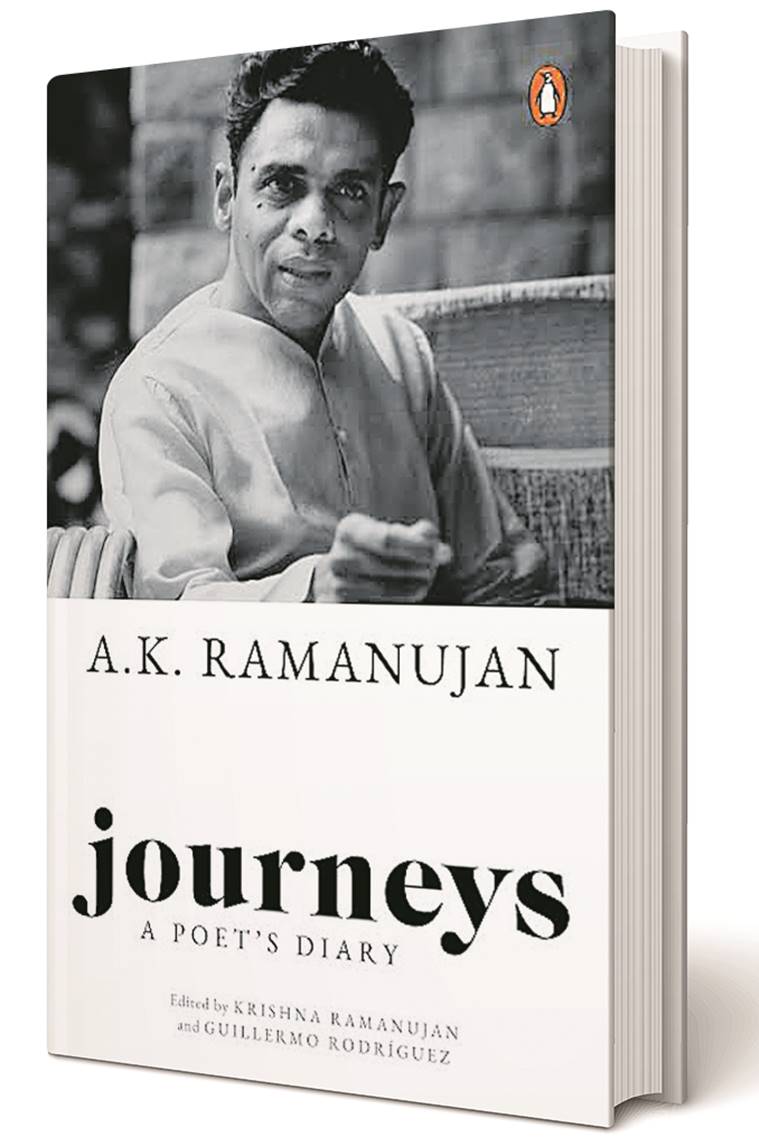

Journeys: A Poet’s diary

A K Ramanujan

Penguin/Hamish Hamilton

384 pages

Rs 599

We met in 1959 at Bloomington, Indiana. It was our first trip to the USA. I was 21, nine years younger than my friend Ramanujan. We were graduate students doing our PhD. Sixty long years have passed. Today we are meeting once again in the pages of his journals. Our most intimate meeting.

This is a reader’s private journey through a poet’s inner self, witnessing a poet’s soul-searching. I feel like an intruder in a private space, peeping into a creator’s innermost self. He is sharing his most private moments, baring his truths, disappointments, surprises, dreams, loves, the process of creation unfolding on every page. Full of self-doubt and self-criticism, and self-improvement routines sincerely planned (but never to be followed!), the journal is also filled with dreams remembered in amazing detail. A poet is honestly searching for his true self, his very soul. Creative? Scholarly? Scared? Confident? He searched for an answer for 50 years in his diaries.

AK Ramanujan was a poet, scholar, multilingual translator and teacher. A brilliant mind endlessly searching for the artist’s self, he is open at times, but very private at other moments. He mentions very few names, uses initials for most, even changes names. “Betray yourself totally in your writing,” he writes, and that is precisely what he does here. For example, he lists the people who ill-treated him, and supplies possible reasons for their dislike. He is totally self-centred in these pages. Except his wife Molly, others do not occupy much space in his life and mind. Of course, the material here has been selected by the editors. We cannot really draw conclusions about Raman’s personal choices.

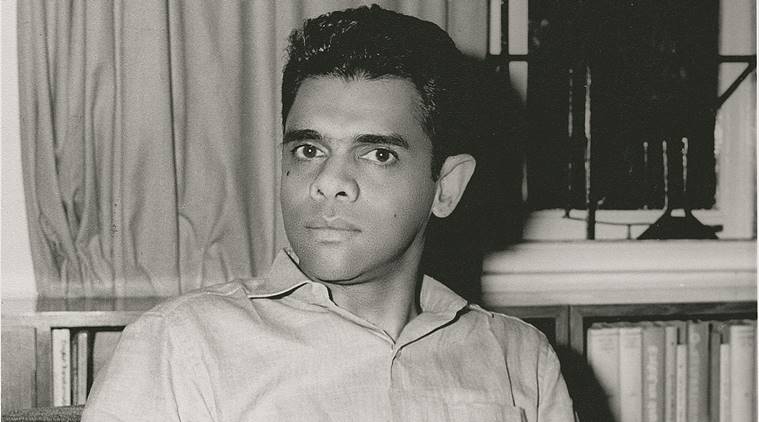

Ramanujan was engrossed in folklore, poetry, translation, language, sex and psychology. How could such an intellectually powerful man be so unsure of himself emotionally? He reasoned that the lack of confidence owed to his thin, high-pitched voice. He even took voice training in the US. A brilliant conversationalist, his thin voice was scarcely noticed when he spoke. The strange diffidence which he expresses in these pages was never visible. The sparkling wit and humour of Raman in conversation could only come from deep self-confidence.

He planned to publish some of these journals, but never did. His son Krishna Ramanujan and the Spanish scholar Guillermo Rodriguez did the job after he was gone. It was possible thanks to the jewel box of AKR papers at the Joseph Regenstein Library in Chicago University. And there’s a fascinating foreword by his old student, close friend and admirer, Girish Karnad.

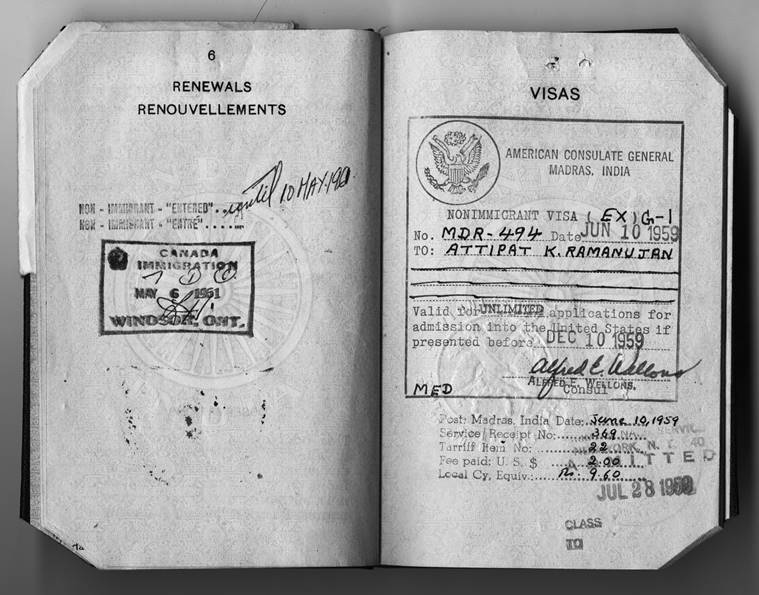

In the first section, ‘Mother India’, Ramanujan is a young man in India discovering himself as a poet. From a Tamil Brahmin background and early literary leanings, his journey has begun towards a meat-eating, whiskey-drinking Western academic life. The second, ‘The Journey’, is an extraordinary travelogue of his first sea voyage to Europe. He uses language like a paintbrush, detailing the sights. With his knowledge of history, art and literature, he is at home everywhere in his journey through several cities. But there are intricately detailed descriptions of intimate public kissing, a sight one does not see in India. Even-handedly, he also mentions strange Indian practices, like men walking the streets holding hands.

In the third section, he is an academic in the US, publishing a lot of poetry, exploring and rediscovering himself in a new culture. The fourth is uncomfortable-making as if you are watching the poet’s most private moments through a half-closed window. We are privy to a brilliant creative mind, totally absorbed in but strangely unsure of itself. His humility is astonishing: invited to a poets’ meet in Jerusalem, he hesitates because two Nobel laureates would be there.

To be a poet is to be in control. Raman never let go. He even critically details the effects of mescaline when he tries it in 1971, alone in an apartment in Madison. His delicate, beautiful poetry documents the experience in images, yet hangs on to logic. The scholar and the poet are both at work, both in control. Raman was always self conscious – in his jokes, in his tales, in his writings. He thought of his self as a writer’s self, even in his private diaries.

The book keeps you spellbound with its amazing intellectual humility. His literary brilliance shines through every carefully-crafted line. The book develops with time, but two things remain the same from 1949 to 1993: his dedication to poetry and his self-doubt.

In 1972, Raman looks back at his pages from the Sixties: “Sickening that one’s thoughts, cravings and self-reproaches have remained the same, said in the self-same words, while everything in one’s circumstances have changed — marriage, children, divorce, travel, a career of 20 years, new intimacies, suicides, aging of friends, books written… One’s self-awareness has stayed out of touch with the self itself and its changes.”

Bloomington, September 1959. Our first day at the university. We were in a queue at the dining hall. A small Indian man with a shock of curly black hair and a thin, high-pitched voice was among us. Happy to find a brown face, I smiled at him. A big smile and shining eyes flashed back. He was an Indian poet in English, the kind I was strongly against. Why should anyone create poetry in any language other than her mother tongue? I wrote poetry too and had a book to my credit, but certainly not in English. Ramanujan said that he had written poetry in Kannada and Tamil, but felt happier writing in English. I did not ask why. I thought I knew. English has a worldwide readership. But perhaps his reasons were different?

We soon became friends and went for long evening walks through the woods, admiring the gorgeous red and gold leaves of fall and discussing life and literature. Once, looking at the leafless skeleton of a wintry tree, with its naked branches spread out in the sky, Raman said, “Look, doesn’t it look like the tree is upside down with its head buried in the ground and its roots clawing the sky?” Every time I see a bare tree in winter, I remember Raman’s words.

Years later, during a walk in Harvard Yard, he mentioned women’s oral tales in Telugu about Rama and Sita. I was then working on Chandrabati, a Bengali woman’s Ramayana, and thought of exploring the genre further. This was well before he wrote his fabulous essay, The 300 Ramayanas, which became controversial in 2011 when Delhi University dropped it from its syllabus following right-wing threats.

I last met Raman in June, 1993. We were both staying at Delhi’s India International Centre. Raman had delivered a glittering speech, as always, about the continuity of folktales through generations. The details keep changing, yet the basic story remains the same. He spoke of a woodcutter, who said that his axe was actually his great-grandfather’s. How was it still so bright and sharp? “Oh, the blade has been changed a few times.” And the wooden handle was not worn either! “Yes, the handle, too, has been replaced a few times, but the axe remains the same.” So does the orally transferred story.

Over dinner that night, Raman said he was returning to Chicago for a surgery which he was uneasy about. His family and friends had assured him that it was very simple and safe. I, too, encouraged him to be relaxed about the surgery, since everyone was saying it was necessary. He remained silent, clearly unconvinced. Back in Chicago, he had the operation against his will, and never regained consciousness. There is a reference to our meeting in the last page of his journal, but my name is changed to Gita (Raman called me Nita). The journal ends the same day, strangely — or maybe not so strangely — with a reference to Yaman, the lord of death.

Poet, writer and academic, Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s works include studies of the Ramayana and literary translation