Written by Shraddha Gome and Harpreet Singh Gupta

On April 15, 2019, a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed in the Supreme Court against Prime Minister Narendra Modi for filing a false affidavit. The petitioner, Saket Gokhale, a former journalist, has alleged irregularities regarding a plot of land, which, as per the land records, still belongs to the PM — but it has been omitted from his recent election affidavits. Recently, Union minister Smriti Irani was accused of falsifying her educational records in her affidavit. Surprisingly, despite the upsurge in the number of complaints of false affidavits, we are yet to see any strict action taken in this regard. Hence, it is important to look into the law governing false affidavits under the under the Representation of People’s Act, 1951 (“RPA”) and examine its effectiveness in curbing this malpractice.

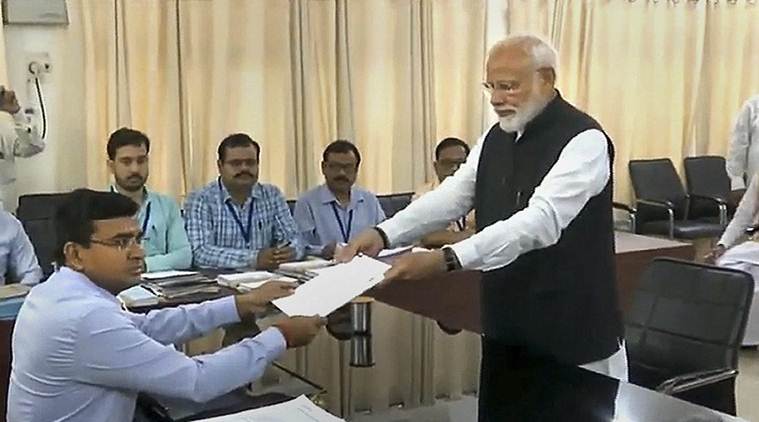

Section 33 of the RPA, read with Rule 4A of the Conduct of the Election Rules, mandates all candidates contesting national/state assembly elections to furnish an affidavit comprising basic information such as their assets, liabilities, educational qualifications and criminal antecedents (if any). Failure to furnish information or filing false information in the affidavit is a penal offence under Section 125A of the RPA which prescribes a penalty of maximum six months or fine or both. However, unlike conviction for offences like bribery, conviction under Section 125A does not result in disqualification of candidate.

Another relevant provision is Section 8A which disqualifies any candidate found guilty of corrupt practice from contesting the election. Section 123 of the RPA defines “Corrupt Practices” to include “bribery”, “undue influence”, appealing to vote or not on grounds of caste, religion etc. What is baffling is that non-disclosure of information has been interpreted as a corrupt practice amounting to disqualification under section 8A, but, the courts’ silent stance in the treatment of filing false information has led to the understanding that filing false information does not amount to corrupt practice. This means that candidates who do not disclose certain information can be disqualified, but those who file false information can only be punished for maximum six months.

In Krishnamoorthy v. Sivakumar & Ors (February 6, 2015), the issue before the SC was whether non-disclosure of criminal antecedents by a candidate in his affidavit amounts to corrupt practice under Section 260 of Tamil Nadu Panchayats Act (which is similar to section 123(2) of RPA). The court ruled that the voter’s right to know the candidate who represents him in Parliament is an integral part of his freedom of speech and expression, guaranteed under the Constitution. Suppressing information about any criminal antecedents creates an impediment to the free exercise of the right to freedom of speech and expression. Therefore, non-disclosure amounts to an undue influence and corrupt practice under Section 123(2) of RPA.

A similar question came up before the SC in Lok Prahari v. Union of India & Ors (February 16, 2018), wherein the court followed the Krishnamoorthy judgment. It held that non-disclosure of information relating to source of income and assets by candidates and their associates, is a corrupt practice. The court laid emphasis on the following paragraph from Krishnamoorthy: “While filing the nomination form, if the requisite information, as has been highlighted by us, relating to criminal antecedents, is not given, indubitably, there is an attempt to suppress, effort to misguide and keep the people in dark. This attempt undeniably and undisputedly is undue influence and, therefore, amounts to corrupt practice.”

Evidently then, furnishing false information which misguides and violates the voters’ right to know their representative is a corrupt practice under the RPA. To reaffirm the same, a petition was filed in the SC in September 2018, seeking directions from the court to declare the filing of false affidavits a corrupt practice, and to direct the legislature towards implementing the recommendations of the 244th Law Commission Report. While the SC agreed in principle that filing a false affidavit for elections is a corrupt practice, it expressed its inability to direct a relevant legislation. It failed to realise that the mere absence of a separate clause declaring the filing of false information as a corrupt practice, does not stop the court from interpreting “undue influence” to include filing of false information. The court should have relied on its earlier judgments in Lok Prahari and Krishnamoorthy to rule that similar to non-disclosure of information, false affidavits will also constitute “undue influence” as they also try to misguide people.

Thus, the SC missed a golden opportunity to prevent the abuse of process and cure a gross error — of treating non-disclosure and filing false information differently. If at all, deliberately filing false information should be dealt with more strictly. In the absence of any specific direction from the SC, there is no clarity on the filing of false affidavits. Candidates are incentivised to file false information since the risk of disqualification exists only in cases of non-disclosure.

The lack of legal clarity relating to false affidavits has led to multiple candidates, including prominent leaders, getting away by filing false information in their election affidavits. It is high time the SC clarifies that filing false affidavits (similar to non-disclosure of certain information) constitutes “undue influence”, which is a “corrupt practice”. Further, to add clarity and discourage false affidavits, the legislature must incorporate threefold changes suggested by the Law Commission in the RPA. First, increase the punishment under Section 125-A to a minimum of two years; second, conviction under this provision should be a ground for disqualification of candidates under Section 8(1) of the RPA; and, third, falsification of affidavits by candidates must also be separately included in section 123 of the RPA as a corrupt practice. These changes are needed to ensure that the voter’s right to information remains paramount, and the candidate’s constitutional right to contest is subservient to it.

The writers are Mumbai-based lawyers and alumni of National Law School of India University, Bengaluru