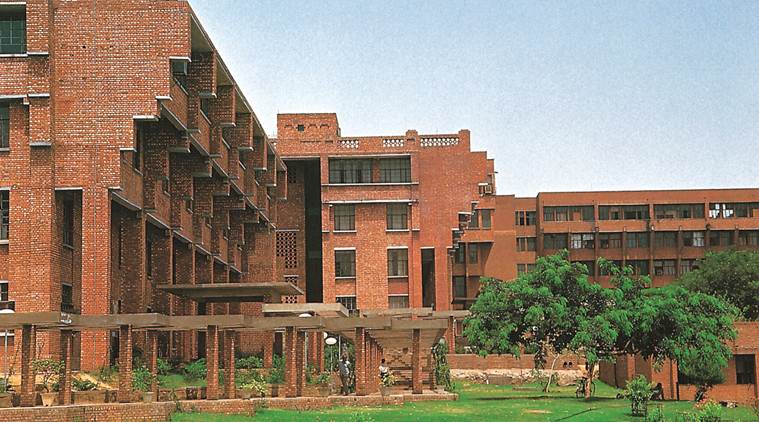

Be the terraces on the Amba Deep Tower at the turn of KG Marg in Delhi, or the brick balconies of Jawaharlal Nehru University, if there one thing architect CP Kukreja knew, it was how to make his buildings climate-sensitive. Founder of the 50-year-old firm CP Kukreja Architects (CPKA), Kukreja passed away last year at the age of 80. A retrospective of his work is on display at the Sushant School of Art and Architecture (SSAA), Ansal University, till May 31. It’s the third in the series of exhibitions on modern Indian architects.

“The aim of these exhibitions is to impart awareness about modern architecture in India as a missing link in Indian architecture history and highlight its significance for our society and future generations. This becomes even more relevant in the light of recent demolitions of these modern buildings,” says Bhawna Dandona, at SSAA, one of the curators of the show.

“Strung Course: Life and work of CP Kukreja” presents a wide range of projects — from institutions and offices to embassies and hospitals. Through drawings, photographs, personal memorabilia and interviews, it showcases how the firm has held its central philosophy of making buildings humane. Kukreja won the Jawaharlal Nehru University project in the late ’60s, when he was barely 32. The first project for the then two-member office was not only a matter of honour but a deep conviction that it had to be a modern building that symbolised a site of learning in independent India.

His son Dikshu affirms his father’s view of looking eastward for inspiration at a time when international architects such as Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn were leaving their imprints on India’s landscape and design minds. Though Kukreja earned his education in architecture and urban planning abroad — Melbourne, Canada and England — it made him aware of the need for sustainable, energy-efficient designs that blended tradition with modernity.

“While he saw the need for modern architecture, he also embraced what was inherently Indian. Context was important to him and he never forgot where his buildings were sited. His research on tropical architecture, which led to his book, explains how design in India should be, and his projects were a demonstration of those principles,” says Dikshu.

If the ’70s established the firm as one to watch out for, Kukreja was open to new explorations in the next decade. In collaboration with well-known Finnish architects Raili and Riema Pietila, he worked on the Chancery, the Ambassador’s Residence and housing at the Finnish embassy in New Delhi. He took the material of exposed bricks many floors higher with the apartments for the Indian Foreign Services Group Housing in the Capital. With cavity wall construction for the exterior, he not only reduced the energy loads but also made the interiors cool and bright with natural light.

Alert to the changing economic climate of the country in the ’90s, Kukreja designed the 18-storey Signature Tower in Gurgaon. One of the first buildings to have curtain-glazing systems, it started the trend for steel-and-glass facades in the IT hub. However, alongside this design was the Amba Deep Tower. “It had many firsts in the way it broke away from the orthogonal forms to the plaster finishes on the facade to bringing art on a large scale with its Persian-inspired tilework. The glass elevators too gave the common man a panoramic view of the city,” says Dikshu. Author Gilles Tillotson calls it the “sultanate tower of our times”.

As the firm moved into the new century, its commitment to the environment grew. CPKA’s recent acquisition of the India arm of Chicago firm dbHMS, known for its sustainability and engineering designs, only reinforce that purpose.

Seen as a commercially successful firm that has won numerous awards, Dikshu reinforces what held his father’s imagination. “My father had a no-fuss approach to architecture. It was meant as a source of shelter, revenue and culture, for peace and tranquillity, all of which embodies a person’s existence,” he adds.