Vibha Bakshi’s latest documentary, Son Rise, opens in Khanda Kheri, Haryana, a village not far from the national capital. It is winter and the air is hazy, men in shawls herd sheep next to a highway, a group of men play cards in a street corner. It is not hard to imagine what life here is like when the chill passes — village after village full of mustard fields under bright blue skies, children playing in the open, women shyly turning their faces away from a stranger’s gaze — it is almost idyllic, making one wonder if it is indeed possible to turn back to a time when a man’s reach did not quite exceed his grasp. But something is rotten in the state of Haryana.

Her camera panning over the sights and sounds of a rural landscape, Bakshi and her team waste no time in identifying the missing piece of the puzzle — family after family in villages across the state boast of sons, and not daughters. “I didn’t quite set out to make a film on female foeticide in Haryana, but once we reached there, there was no way we could have ignored what was right in front of us,” says Bakshi. In 2016, the 48-year-old filmmaker was travelling through the northern states, screening her National Award-winning documentary, Daughters of Mother India, that explored the impact the brutal December 2012 gangrape of a Delhi student had on the citizens, the police and the judiciary. “At one of these screenings, a woman came over to me and told me that I should meet a farmer who had married a gangrape survivor and was fighting for justice. There was no name of the person or the village, but I knew I had to track him down,” says Bakshi. She sought the help of local police, and found that indeed, many knew of this man, who lived in Jind, one of the oldest districts in the state. “Most people referred to him in a way that indicated that they thought he’d done something strange. But to me, Jitender Chhatar is a hero,” she says.

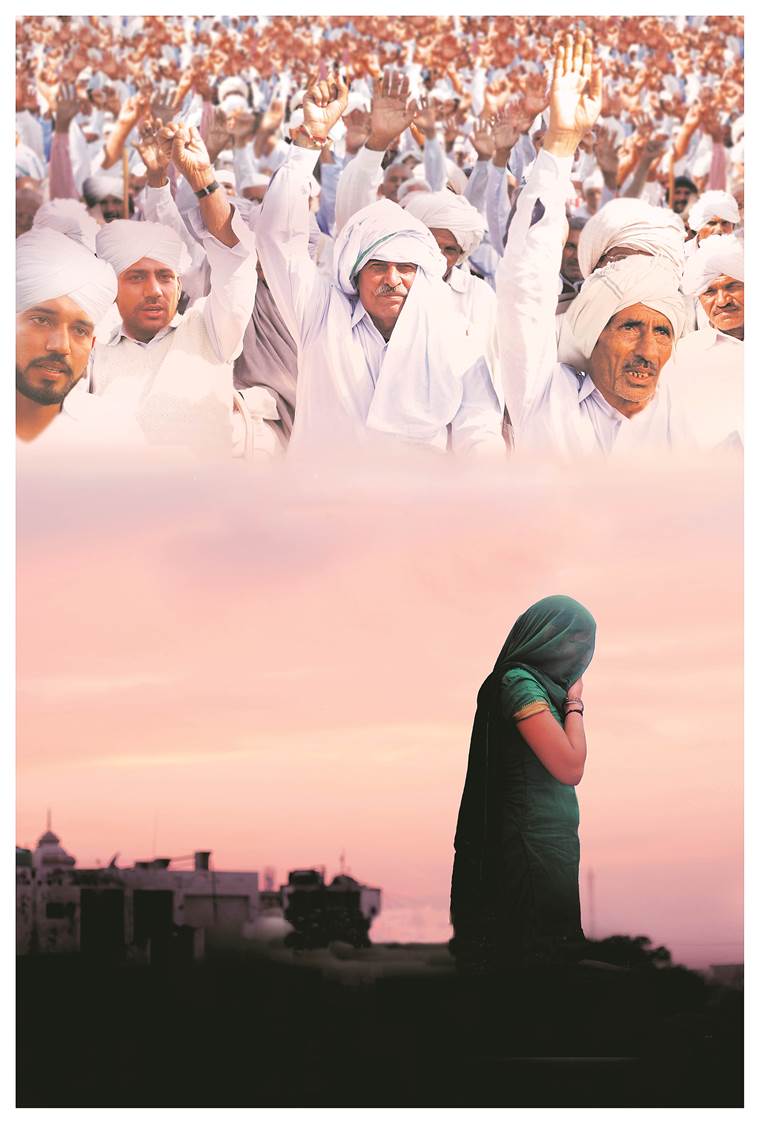

It would have been easy to simply focus on his struggles to bring his wife’s rapists to justice, says Bakshi. “But crimes don’t take place in isolation, especially heinous ones such as gangrape, where one’s personhood is completely ignored,” she says. So, she took a step back to look at the entire picture. Son Rise examines the cause and effect of Haryana’s skewed gender ratio; it traces the consequences of hushed up abortions, the nearly complete absence of women in the state’s villages, the bride buying/bride kidnapping traffic that follows, and the numerous crimes against women that have become so commonplace that its victims are reduced to a mere statistic. Bakshi discovers that all is not lost — there are still a few good men who want to fight for women’s rights, and perhaps, for the first time in their lives, are beginning to understand that they will have to combat other men at every step of the way.

“Sunil Jaglan, Bibipur’s village chief, is a crusader for equal rights — from opening a vocation centre for women, to teaching them their rights, the father of two daughters is such a voice of reason that his detractors are constantly slapping court cases on him. There’s also Baljit Singh Malik, a Khap leader, who oversees 1,440 villages across Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan — he took it upon himself to declare that women no longer needed to wear ghunghat, and that inter-caste marriages should not be opposed,” says Bakshi. But at the heart of the film is Chhatar’s long and lonely battle for justice and closure; both seem elusive for years to come. “The film’s editor, Hemanti Sarkar, and I exercised a lot of restraint; a story about a rape is not about the survivor or its perpetrators. We wanted to show the audience how we as a society have got to this point where such a thing can happen with impunity. Most of all, we wanted to show the unshakable resolve of ordinary people caught up in extraordinary circumstances, who continue to fight, no matter what,” she says.

Shot over two years, from 2016 till 2018, Son Rise had its first screening in February this year, and since then, the buzz around the film is getting louder. Last week, in an unprecedented show of support, the Consular Corps, comprising consul generals of 10 countries — Brazil, USA, Italy, Canada, Norway, Sweden, South Africa, France, New Zealand and Sri Lanka — along with UN Women and the Films Division, hosted a screening of Son Rise at the newly-opened Museum of Indian Cinema in Mumbai’s Pedder Road. “My film is not going to solve the problem, but if it can start the conversation, I have succeeded,” says Bakshi.