A primordial bone found in our primate ancestors but thought to be redundant and rapidly dwindling in humans — appears to have made a quiet comeback over the past century.

A primordial bone found in our primate ancestors but thought to be redundant and rapidly dwindling in humans — appears to have made a quiet comeback over the past century.Scientists from Imperial College London have admitted they are stumped as to why the fabella, a small bone buried in a tendon behind the knee, is now three times more common than it was in the early 1900s.

They speculate that its reemergence could be linked to joint problems, and understanding why could help treat or protect those most at risk. “We don’t know what the fabella’s function is — nobody has ever looked into it,” lead author Michael Berthaume, said.

“We are taught the human skeleton contains 206 bones, but our study challenges this. The fabella is a bone that has no apparent function and causes pain and discomfort to some and might require its removal.”

People with osteoarthritis of the knee are twice likely to have a fabella, and it can interfere with joint operations, but it is not clear if the tiny bone is the cause — or a symptom — of joint problems.

Berthaume likened it to the appendix, another potentially harmful vestigial organ. But unlike the appendix, which is shrinking in humans but is larger in other mammals, fabellae are becoming more common.

The findings, published in the ‘Journal of Anatomy’, come from over 21,000 scientific articles, detailing the physiology of 21,676 knees in in 21 countries over the past 150 years. It shows in 1918, 11.2% of the world’s population had fabellae, but today that has risen to 39% — a 3.5-fold increase.

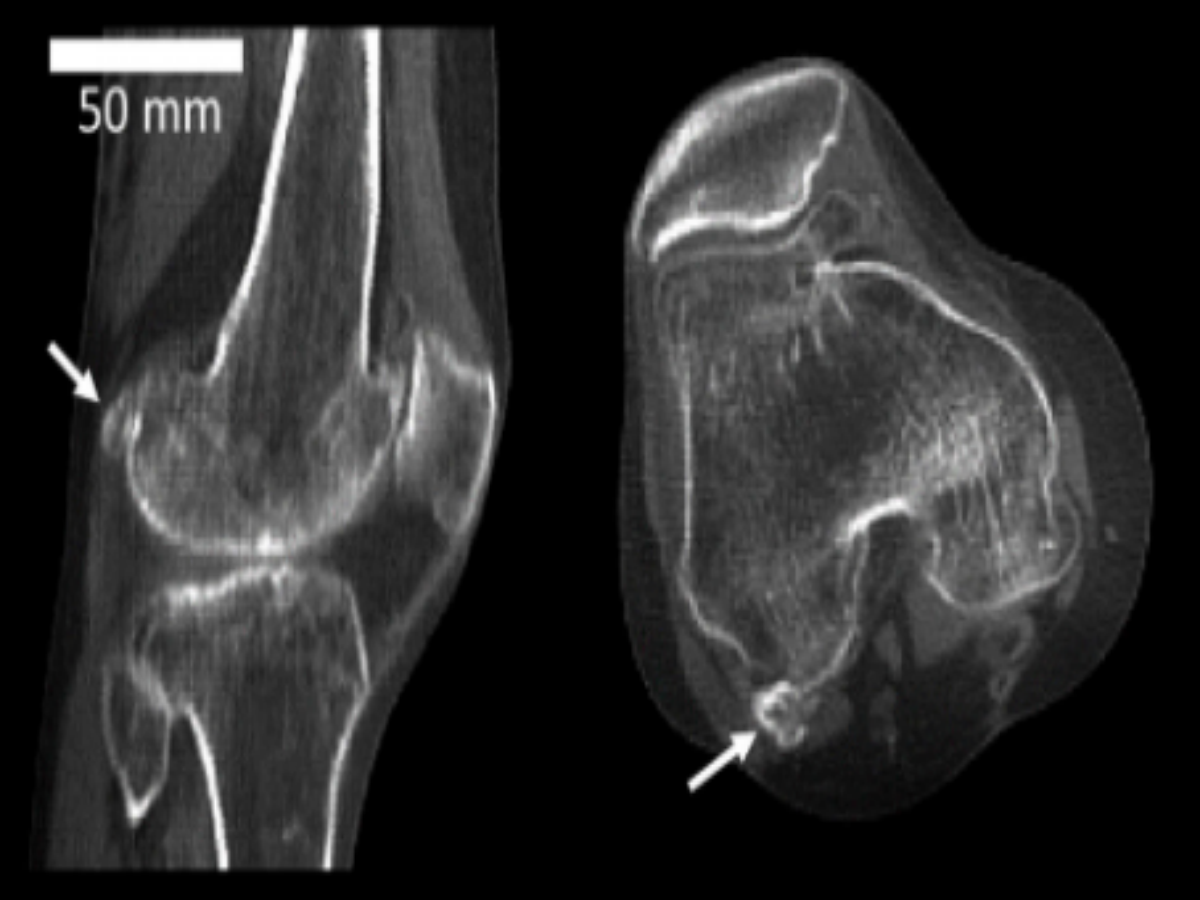

Fabellae are sesamoid bones, which means they grow in the tendon of a muscle — the knee cap being the largest example in the human body.

Berthaume and colleagues speculate that it could be the shifting forces on the knee cap that are behind its comeback. “The average human, today, is better nourished, meaning we are taller and heavier,” he said “This came with longer shinbones and larger calf muscles — changes which both put the knee under pressure. This could explain why fabellae are more common now.”