Aasmann jora fakirre bhai, Jamin jora ketha (The friend of the fakirs is the sky, the friend of the earth is the kantha)

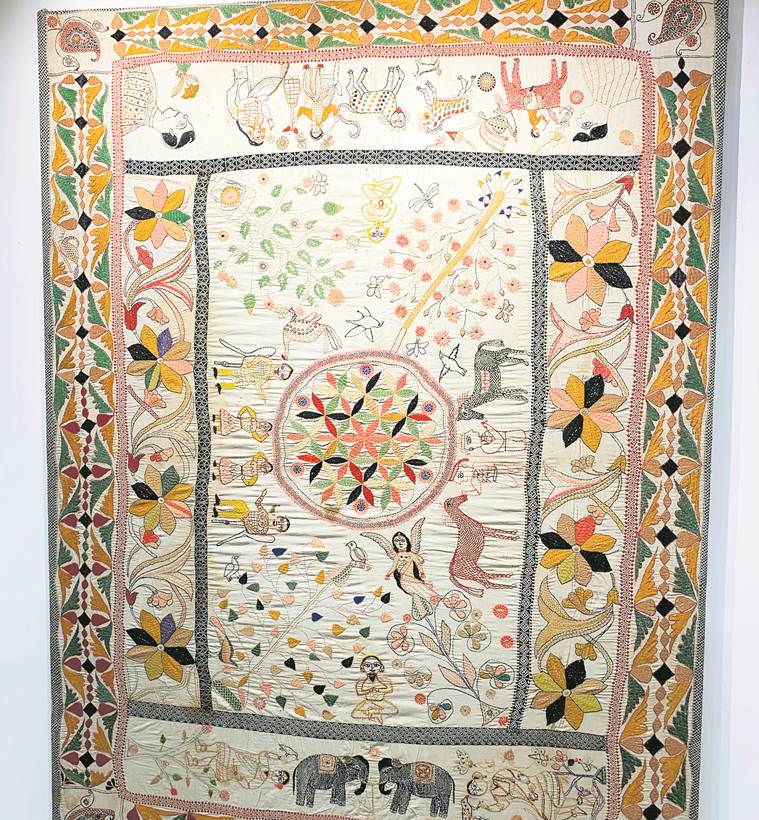

Textile art historian Jasleen Dhamija draws attention to a Baul song that mentions one of India’s oldest forms of embroidery, the Kantha, on a wall at India International Centre. The finest examples of this intricate needlework made by the women of West Bengal on small pieces of cloth depict thumbnails of children looking at animals and acrobats hanging in the air at a circus, and life around the railway station near Shantiniketan. Rural women working on the year’s harvest in their paddy fields and their children hanging from trees are also seen in another corner. These images are a result of late sculptor Meera Mukherjee’s engagement with the village women in Kolkata. They are some of the many themes that are explored in the exhibition “The Needle Reverence”, centred around Kantha.

These contemporary pieces of Kantha made in the 1990s rest alongside earliest pieces dating back to the pre-independence era. Within these traditional Kanthas, full of animals, birds and trees — mostly what its creators saw around them — there’s an inscription of a village rhyme for a newborn. It requests birds to not fly away and even if they do, to remember the creator and come back. As he pinpoints at the Bengali text hinting at “With blessings from” and names stitched on a few quilts on display, Siddhartha Tagore, a contributor to the exhibition and owner of Art Konsult gallery, says, “Most of the Kanthas in West Bengal were quilt Kanthas, where the mother or grandmother would make them for the newly born child, as a gift of reverence. These would be spread on the bed or floors, and were recycled. The lep Kanthas were made out of three to four layers of old cotton saris, and covered with the dhoti on top and the bottom, on which long intricate patterns were stitched. The women, since they menstruate, believed that their old saris were not considered good for the new born. Kanthas made from dhotis was considered more pure.”

The aim of the textile pieces on display, in the form of shawls and bed covers to book and table covers, is simple — to highlight the art of Kantha, derived from the Sanskrit word kantho, for rags. From pre-partition East Bengal, an old, faded and ageing Kantha used as a shawl shows Tantric elements, and is adorned with deers, parrots, snakes, crocodiles, elephants and men. Siddhartha believes that Kantha has various manifestations, the Sujani quilts of Bihar for instance.

Having grown up in Kolkata, seeing Kantha stored in trunks, thanks to the efforts of his collector father Subho Tagore, an artist himself, Siddhartha says, “Orissa has Kantha too but it never came into prominence. Only the tribals wear it as shawls.” The late Kanthas transformed into saris, he says, where a plain sari would be embroidered upon. Siddhartha remembers one such sari he bought that had an imagery of Satyajit Ray’s 1977 classic Shatranj Ke Khilari.

Apart from Kanthas used for religious rituals, the most interesting exploration of the exhibition is of a Kantha inscribed with the words “Hare Rama Hare Krishna” in both Bengali and Assamese. Siddhartha feels this was most probably made on the border of Assam and Bengal, revealing the cross-cultural amalgamation of the Kantha. The earliest Kanthas featured soldiers of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 with their guns and the heroes of Mahabharata and Ramayana.

Dolly Narang, who has brought together Mukherjee’s collection of Kanthas, which are decorative pieces, believes that Kanthas made from old torn saris are the finest display of recycling in Indian culture. “These were usually made from old worn out saris that were made beautiful again using embroidery. It was a community effort, where women gathered and made them. It’s different now,”she says.