How social media and messaging platforms affect the choice India makes this summer is the subject of this edition of Decoding 2019.

Rima M | Rakesh Sharma

Moneycontrol Contributors

In the early decades of its inception, the state-run media platform Doordarshan dispensed, if not slanted then, sanitised news. However the news streaming scenario has experienced a dramatic upheaval in the recent years not just in India but the world over. As a piece on thoughtco pointed out in January 2019, and as writer Tom Murse said, the use of social media, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, in politics has dramatically changed the way campaigns are run and how citizens interact with their elected officials and politics. We saw the power of social media and the fake news therein, in the American presidential elections and the Brexit vote. Social media have been used by political parties as both a tool of empowerment and oppression, but the latter has tended to trump the former. From Bolsonaro's WhatsApp campaigns to influence voters in Brazil to the Philippines' President Rodrigo Duterte's use of Facebook and troll armies, we have seen the rise and expansion of social media and its many tools to derail democracy.

Indian elections - the biggest democratic spectacle in the world with about 900 million eligible voters - are a fertile ground for the explosion of social media. We saw it happen in 2014, and we are seeing it happen again - deeper and grander - in 2019. Facebook’s announcement earlier in the week that it had taken down hundreds of pages linked to the Congress and the BJP has cast the spotlight yet again on the onslaught of disinformation permeating what has become the primary battleground in the world's largest general election. Major international news outlets have already dubbed this the WhatsApp election. The rise in 4G connectivity, the explosion in smartphone ownership, and the expansion of internet access the country have made communicating with the electorate at an intimate level easier, but with it have also come the perils of such communication - fake news and unchecked propaganda. One post that went viral on social media had BJP head Amit Shah saying, "We agree that for election, we need a war." That post, intended to showcase the BJP as a warmongering party, was seen by 2.5 million viewers and shared several thousand times before being taken down. It was proven to be a fake. Another post which went viral on WhatsApp intended to showcase the Congress as soft on militancy, and claimed that a party leader had promised money to free terrorists and stonepelters. That was proven to be false as well. And by the time the truth catches up limping and gasping, the lie would have circled the earth many time over.

How social media and messaging platforms affect the choice India makes this summer is the subject of this edition of Decoding 2019 with me Rakesh Sharma on Moneycontrol.

The immediacy factor

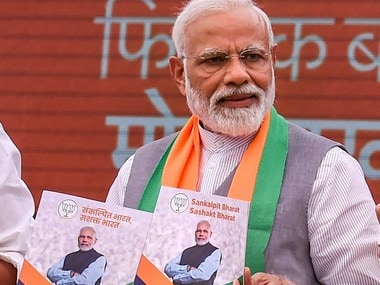

We saw a hint of things to come in 2014. Bypassing the unspoken media embargo that had been placed on him by conventional media houses thanks to his alleged involvement in the Gujarat riots of 2002, then prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi, with the marketing genius of advertising heavyweights such as Madison World, McCaan Group, Ogilvy and Mather, and a corpus of a hundred million dollars, spoke directly to millions of voters through social media. "Brand Modi" was aired into homes and minds not through traditional media, but through social media - Facebook, YouTube, Twitter. Traditional media followed soon after, but the primacy of social media in that campaign should give us an indication of just how strong this medium has become.

After coming to power, the affiliation of the BJP with social media did not end. If anything, it grew. The IT Cell and its supporting sites labelled anyone who had anything uncomplimentary to say about the policies of the party "anti-national" or "sickular" or "Libtard" or "presstitute." Memetic warfare became the norm in Indian polity; hashtags became the weaponry. It was all political theatre played out on the soundstage of social media. If in the process blood was shed, you could be certain it was not fake, even if the "news" was. The INC is no stranger to these tactics either. Even though it was a Johnny-come-lately in the war waged on social media, the arrows in its quiver are shaped much the same. Memes, hashtags, and their own troll army used humour and abuse alike to berate the prime minister and his supporters, to say nothing of the attempts at peddling its own Janaardhan-tanik-der-se brand of "soft Hindutva."

Neither party comes out of this clean. In the unending cycle of punch-counterpunch and propaganda-counterpropaganda, both parties (and their alliances) are responsible for the negativity that permeates any discourse, and both parties are responsible for the normalisation of hate speech online. But the adoption of similar strategies by both the factions tells you one thing - the power of the platform they are deploying these strategies on.

On the one hand, the prevalence of social media in politics has made elected officials and candidates for public office more accountable and accessible to voters but on the other hand, the ability to publish content and broadcast it to millions of people instantaneously allows campaigns to carefully manage their candidates’ images - real or fake - based on rich sets of analytics in real time and at almost no cost.

The thoughtco piece says, "Social media tools including Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube allow politicians to speak directly to voters without spending a dime. Using those social media allows politicians to circumvent the traditional method of reaching voters through paid advertising or earned media. It has become fairly common for political campaigns to produce commercials and publish them for free on YouTube instead of, or in addition to, paying for time on television or the radio. Often times, journalists covering campaigns will write about those YouTube ads, essentially broadcasting their message to a wider audience at no cost to the politicians. Twitter and Facebook have become instrumental in organizing campaigns. They allow like-minded voters and activists to easily share news and information such as campaign events with each other. That's what the "Share" function on Facebook and "retweet" feature of Twitter are for."

Tools like hashtags are used by political parties for multiple purposes. To label rivals with disparaging monikers. To reiterate a point they want ingrained in the minds of citizens. Nobody has used Twitter more extensively than the US President Donald Trump who has often taken on other countries, leaders, journalists, late night comedy shows, actors and even global warming, to establish a rapport with his base and to show his followers that he is his own man and will peddle his own ignorance with complete arrogance because he can do it, just the way they expect him to. And social media have enabled him to. They have, after all, until recently claimed they are merely content aggregators and not curators.

As the piece says, Donald Trump used Twitter heavily in his 2016 presidential campaign and with signature "stable genius" style, he said using his "best words," "I like it because I can get also my point of view out there, and my point of view is very important to a lot of people that are looking at me."

The freedom to tailor content

Social media offers unlimited freedom to dispense messaging convenient to political parties and they don't do so randomly. As the piece says, "political campaigns can tap into a wealth of information or analytics about the people who are following them on social media, and customize their messages based on selected demographics. In other words, a campaign may find one message appropriate for voters under 30 years old will not be as effective with over 60 years old."

Yes, what you consume is methodically cooked and seasoned.

But social media can serve many purposes. It is not just an effective tool for candidates backed by an endless stream of money but those without financial backing, especially candidates who want to involve their voting base in the campaigning process through crowd funding as was the case with Kanhaiya Kumar recently whose site was incidentally hacked even though it had raised a considerable amount of money.

What social media intervention does most effectively and frighteningly is to take focus away from reality to perception and to create a glut of multiple, colliding viewpoints where it is hard to sift the truth from propaganda. On an earlier podcast, we spoke about lynchings in India triggered by Whatsapp forwards and how spurious messaging resulted in a pizzeria shooting in the US ("pizzagate"), and the smearing of gun violence victims as crisis actors, just to drive home the point that fake news and political intent are often inter-linked. The vitriol directed towards journalists like Rana Ayyub and the murder attempt made against student leader Umar Khalid, labelled as an “anti -national” shows disturbing trends that need to be studied closely. In the US, we saw one agitated citizen who had stockpiled weapons and ammunition hoping to gun down several prominent senators, journalists, and newscasters, based on what the relentless fake news machinery had fed him.

As the piece says, "Direct access to voters also has its downside. Handlers and public-relations professionals often manage a candidate’s image. Many campaigns hire staffers to monitor their social media channels for a negative response and scrub anything unflattering. But such a bunker-like mentality can make a campaign appear defensive and closed off from the public."

The Facebook family's hold on Indian eyeballs

In India, the usage of these platforms cannot be over-emphasised. The Facebook family of platforms - Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram - accounts for 95% of social or communication app usage in the country. Sangeeta Mahapatra, visiting fellow, Institute of Asian Studies, German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Hamburg, who closely watches social media trends and politics, says, "If one reads Statista figures along with that of Hootsuite, one finds that around 97 percent of smartphone owners in India use mobile apps, out of which 96 percent use WhatsApp.”

Facebook and Twitter have taken several steps to make sure their platforms are not abused. WhatsApp is apparently using artificial intelligence to detect and ban accounts that spread "problematic content," while Facebook is labeling political advertisements and partnering with Indian fact-checkers. We also mentioned earlier that hundreds of pages have been taken down by Facebook. Twitter has announced initiatives to crack down on "bad-faith actors," and is working closely with political parties and election authorities to ensure its platform isn't compromised during the polls. Colin Crowell, Twitter's global public policy head, said in a statement in February, "We deeply respect the integrity of the election process and are committed to providing a service that fosters and facilitates free and open democratic debate," adding that the Indian elections were a top priority for the company.

Social media etiquette and responsibility were also stressed upon by the Chief Election Commissioner Sunil Arora. Parties will also be required to get political ads on social media pre-approved by the Election Commission and declare how much they have spent on social media advertising. Candidates have also been required to share details of their social media accounts with election authorities. "Facebook, Twitter, Google and YouTube have committed in writing to ensure that any political advertisement published on their platforms will be certified," Arora said.

As for fake news on WhatsApp, especially following the lynchings, and now continuing into the elections, labels on forwarded messages and an awareness campaign on radio, TV, and print media have been instituted. The messaging platform also limited to five the number of chats a single message can be forwarded to. But each WhatsApp group can have up to 256 people, meaning a message can still reach 1,280 people at the touch of a button. As Time reported, "Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has drawn up plans to have three WhatsApp groups for each of India’s 927,533 polling booths, according to reports. With each group containing a maximum of 256 members, that number of group chats could theoretically reach more than 700 million people out of India’s population of 1.3 billion." Amit Malviya, head of the BJP IT cell, has said, "The upcoming elections will be fought on the mobile phone. In a way, you could say they would be WhatsApp elections." A taste of that was seen in the Karnataka assembly elections when the BJP alone created as many as 23,000-25,000 WhatsApp groups. WhatsApp is a particularly useful tool unlike carpet campaigning because the message forwarded to you is usually by a person you know. This "ecosystem strategy" is one that helps improve legitimacy and build scale.

If each of the 29 states were to have 15,000 WhatsApp groups, the catchment population would be about 110 million citizens. As the ET noted, just over 170 million votes helped deliver the Lok Sabha to the BJP in 2014. Perhaps the BJP, better than any other party, knows this. Misinformation there is rampant, and Whatsapp being encrypted, checking for them that much harder. Take one forward: “Wherever you look nowadays you will see only Muslim men and women,” it read. “700 million Hindus, 650 million Muslims,” As Time magazine noted, in actual fact, 80% of Indians (approximately 1.1 billion) are Hindu, compared to 14% (approximately 188 million) who are Muslim, according to the most recent census in 2011.

How politics in India is shaped by social media

India saw an unprecedented use of social media in the 2014 elections and in the years that followed and it prompted a well-known journalist to coin the word, Whatsapp University which has avidly promoted news of fake awards, fake images passing off as glittering Indian cities, foreign buildings awash in Indian colours but most disturbingly doctored videos and images to spread communal unrest. This has created a slew of fact checking websites but it is easy to see the harm such unverified but compelling content can unleash.

Studies have come up with mindboggling numbers while indicating who spends how much on social media political posturing and it is clear, the focus has shifted from manifestos and report cards of governments in power to perception and image building.

As the piece on thoughtco says, “The value of social media is in its immediacy. Politicians and campaigns do absolutely nothing without first knowing how their policy statements or moves will play among the electorate, and Twitter and Facebook both allow them to instantaneously gauge how the public is responding to an issue or controversy. Politicians can then adjust their campaigns accordingly, in real time, without the use of high-priced consultants or expensive polling.”

On one hand, social media tools allow citizens to easily join together to petition the government and their elected officials, leveraging their numbers against the influence of powerful lobbyists and monied special interests but on the other, lobbyists and special interest cliques still have the upper hand. His hope is that the day will come when the power of social media allows like-minded citizens to join together in ways that will be just as powerful as those trying to influence them.

A 2017 piece on Digitalvidya by Vikrant Patil posted the findings of a study on “ Social Media and Politics” and remarked how the success of BJP’s online campaign in 2014 Lok Sabha election brought about the biggest change in Indian politics with even regional parties understanding the power of social media.These elections also shifted the focus of parties from rural issues to urban voters because of their familiarity with social media and their ease of connectivity via laptops, desktops or internet powered mobiles.

For sure, parties still spend large sums of money, says the piece, on posters, cut-outs, fliers, graffiti and rallies, but social media is now an indispensable campaigning tool.

If it is used judiciously is the question.

Are social media platforms finally becoming proactive?

The role of social media has come under scanner since Donald Trump's election especially as far as Facebook is concerned and in previous podcasts we have focussed on how Mark Zuckerberg has had to answer questions about the accountability of social media amid rumours of Russian bots manipulating the US elections, and incendiary content that has grown unmonitored under his watch. The live streaming of a mosque attack in Christchurch, New Zealand has shown that if unchecked, social media can be weaponised to do more harm than good. The American election was a perfect example of how polarity can be created through spreading rumours about rivals, creating confusion, and diluting the credibility of far more seasoned political rivals.

Facebook announced in March that it finally intends to ban content that glorifies white nationalism and separatism. "It's clear that these concepts are deeply linked to organized hate groups and have no place on our services," the company said in a statement. This news came after Facebook’s extensive discussions with civil society groups and race relations experts over the last three months.

Recently, news broke that Facebook has deleted 712 accounts and 390 pages in India and Pakistan for “inauthentic behaviour”, many linked to India’s opposition Congress party days before a national election, and others related to Pakistan’s military.

This came in the wake of increasing vigilance on part of social media giants post criticism that they have allowed their platforms to be abused for political purposes or to spread misinformation.

This happened, as some news reports pointed out, in an environment where all parties, including the ruling party and the prime minister himself and many other leaders continue to use Facebook to send political messages to millions, not to mention the countless unverified pages that run their own toxic campaigns.

Facebook said it had taken down 549 accounts and 138 pages linked to India’s Congress for “coordinated inauthentic behaviour”.

In a Tweet though, Congress said that none of its official pages or those run by its verified volunteers had been taken down. The party awaits a response from Facebook to provide a list of all pages and accounts which were removed, it said.

While quoting a Facebook statement in this regard, Reuters however reported the bit that did not get much air time in virulent news channels. The fact that Facebook also removed 15 accounts linked to an Indian IT company which, among other things, issued posts on Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and alleged misconduct of political opponents including Congress.

Reuters said that the Digital Forensic Research Lab at think tank Atlantic Council, which partnered with Facebook for the review, said the accounts linked to Congress pushed satirical posts, while pro-BJP pages “carried vitriolic posts against opposition leaders. The fact that partisans on both sides resorted to such tactics is a troubling feature.

The Reuters report written by Aditya Kalra and Saad Sayeed mentioned the removal of pages connected to Indian IT firm Silver Touch thought to be “associated with” a mobile app promoted by Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). We quote, “After BJP’s IT head, Amit Malviya, told Reuters both the party and the app had “nothing to do with Silver Touch”, Facebook in a new statement said it had “seen no evidence to date of Silver Touch being associated with the NaMo App on our platform, referring to the Narendra Modi app.”

More to the picture than meets the eye?

A Quartz India report written by Aria Thaker however says there is more to Facebook’s purge of Indian political pages than meets the eye.

We quote from piece, “The social media site’s announcement that it had taken down Indian accounts engaged in “coordinated inauthentic behaviour,” and the ensuing media coverage, suggested that the development had a lopsided effect on the Indian National Congress. After all, of the over 700 political pages and accounts that Facebook said it had removed, 687 were linked to the main opposition party, while only 15 were associated with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Reports, though, say that the number of BJP-linked pages taken down could be over 200, even if not specified directly in Facebook’s blog post. Nevertheless, a look beyond the mere number of pages that were affected shows that the removals have been far more damaging for the BJP.

For starters, the 15 pro-BJP pages removed were all linked to Silver Touch, an Ahmedabad-based IT firm that has reportedly developed Modi’s official app, besides working on several government projects. While Facebook named only one page in this group—The India Eye—it alone had over 2.5 million followers and was well established, included in every user’s default news feed in the NaMo app.”

The piece cites Ben Nimmo, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFR Lab), who said and we quote, “The pro-BJP campaign was big and long-lasting. It picked up over 2 million followers, and managed to stay below the radar for years. The Congress campaign that was removed, was smaller, and its pages didn’t have so much impact individually. It looks like they were trying to build up impact by running lots of micro-pages, rather than one big one.”

The piece further says that Twitter chatter indicates that The India Eye isn’t the only pro-BJP page to have been removed. Pratik Sinha, co-founder of fact-checking website AltNews, tweeted a list of screenshots of different individuals who manage pro-right wing Facebook pages claiming they had been unpublished.

We quote, “Many RW accounts are furious that their FB pages or pages of people they know have been unpublished/deleted. Yet Facebook press release talks about exactly 1 RW page - The India Eye. Why so? Some of these pages are quite notable, including the one belonging to My Nation, a right-wing digital publication of a BJP parliamentarian.

Abhijit Iyer-Mitra, a right-wing defence analyst, claimed “hundreds” of right-wing accounts had been deleted by Facebook. Other major right-wing influencers initially tweeted along these lines, only to later delete their comments."

Nimmo added further, “The big difference was that the INC operation could afford to lose some of its pages without putting a big dent in its overall operation,” Nimmo said. “The takedown of the pro-BJP pages will have much more impact on the overall operation, because their followings were so much bigger.”

A game-changing tool

How game-changing social media content has been can be gauged from a piece published by The Verge which cites a September 2018 BuzzFeed News feature that showed, how in the Philippines, much of the extreme political rhetoric on Facebook props up Philippine President Duterte’s authoritarian reign. And how from the very beginning of Duterte’s presidential campaign, Facebook was an essential tool for Duterte fans to freely spread coordinated messages on Facebook — especially because, thanks to deals that the company struck with local carriers, Facebook is free to use in the Philippines for anyone who has a smartphone.

The Verge article also points out that Trump spent $3.6 million on Facebook ads from Dec. 30 to March 23, according to data compiled by researchers at the Online Advertising Transparency Project, an ongoing study launched last year at New York University that tracks political ad spending through Facebook’s publicly available political ad archive.

The point being that in authoritarian regimes, censorship and control of social media is another way of strengthening political clout as in China where People.cn, the digital arm of the main propaganda outlet for China’s ruling party makes a lot of money by “scrubbing” inconvenient content.

And finally...

What needs to be understood finally is how a media tool in the hands of political leaders can hamper dissent and curb democratic voices. Compare the clout of political pages flush with money to the cash strapped journalism of slain writer Gauri Lankesh, who as the The New York Times said in a piece recently, refused to allow advertisements in her newspaper Gauri Lankesh Patrike, which she felt, was necessary to ward off the corruption and outside pressure that often compromise the Indian press.

We quote, “Lankesh Patrike ran on subscriptions and newsstand sales, supplemented by a book-publishing sideline. But the paper’s financial situation had become so dire that she had decided, for the first time, to run ads in a forthcoming special holiday issue.”

That day of course did not come because of her untimely demise.

What the piece says though is that it was her political activism and her lively social media presence that had extended her reach far beyond the paper’s print run. The NYT said, “At a time of intense vitriol against the press in India, she was a fearless, sometimes reckless critic of the right-wing, Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, which has held power in India since 2014. Her paper was a tabloid in every sense, gleefully sensational and indifferent to decorum. But the vehemence and humor of her polemics in defense of pluralism and minority rights had made her a beloved figure to an increasingly embattled opposition.”

Rollo Romig, the writer of the NYT piece added, “By the end of May, national elections will determine if Modi and the BJP are elected to another five years. It is likely to be the ugliest campaign season in India’s history. Hostility toward journalists and opposition figures is intensifying as voting day approaches. The police last year arrested 11 opposition activists and lawyers on what appear to have been flimsy charges of instigating violence at an event in Maharashtra, and in February arrested, on apparently even thinner evidence, the prominent caste scholar Anand Teltumbde. Tensions have further risen since Feb. 14, when a suicide bomber killed 40 Indian soldiers in Kashmir, setting off a series of skirmishes with Pakistan that are likely to politically benefit the BJP.”

If you think The New York Times (and me) are taking shots only at the BJP, you could not be more wrong, as the piece does not absolve the Congress Party either and points out how, despite a generally secular politics and social democratic demeanour, it has undoubtedly been guilty at times of suppressing the press and of condoning the mass slaughter of religious minorities. We can add the crackdown on the press during Emergency to that list.

But perhaps it is the age of social media that has made it easy for hate rhetoric to spread faster than it ever has.

As the piece points, in this rhetoric, being Indian is equated with being Hindu, and religious minorities are spoken of as if they were foreigners. Critics are branded as “anti-national.” Advocates of a secular Indian state — which the Indian constitution calls for in its very first sentence — are called “sickulars.”

What Gauri Lankesh’s demise has established though is that in the end, the accountability to sift fact from fiction, justice from injustice, truth from accountability does not just lie with the press, media platforms, politicians or social media entities.

It lies with the citizens who must in the end choose their version of India through their votes because their volition finally is the most powerful democratic tool. One that can set the tone for how democracy fares in the years to come. And much of how they decide, and much of what they are told they need, have come thanks to little apps on their smartphones. How smart a choice that leads people to make, is anyone's guess.