At the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Parul Dave Mukherji, a professor at the School of Arts & Aesthetics in Jawaharlal Nehru University, spoke about her long association with eminent artist Haku Shah, who passed away recently. In the mid 1980s, textile mill worker Chatur Lal, from Ahmedabad, had lost his job. Being a regular visitor at home, Haku was curious about Lal’s community. After knowing that he belonged to the mochi community, Haku asked if Lal’s wife Saroj would be interested in making quilts. Soon Saroj was handed an old piece of cloth to do applique work themed around any goddess she worshipped. She chose the dark goddess Chamunda. Her works later made it to the ‘Unknown India’ exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1968 that Haku had curated.

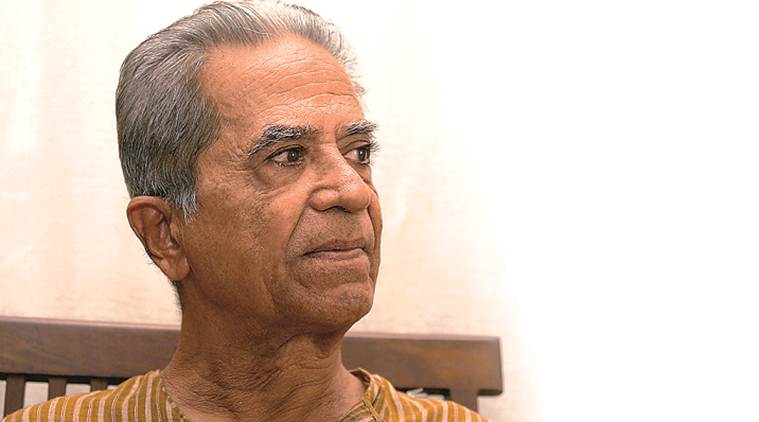

The meeting held in memory of Haku, the late Valod-born artist, a Padma Shri awardee, Rockefeller Foundation fellow, and Kala Ratna awardee, had well-known names from the art fraternity, who gathered on Saturday evening in the Capital.

In the early ’60s, Haku was associated with the formative years of National Institute of Design, and had set up the tribal museum at Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad. “In the mid 1980s, while studying art history at MS University, Baroda, professor Gulammohammed Sheikh stressed upon how important it was for students trained in art schools to understand the deep divide that existed between artists from village communities and artists trained in an art school. Haku Shah was a prime example of someone who could handle these asymmetries in a social world within which he operated,” says Mukherji.

As he spoke of fond memories of his father, Haku’s photographer son Parthiv Shah recalled his days as a seven year old, when a woman would come to his house every day, with a basket on her head, to sell clay toys. “My father would enquire where she stayed and what her husband did for a living; he was a kabadiwala. There was always a kind of interesting relation, it was not just a give and take relationship,” he said.

Parthiv went on to highlight how Haku’s art practice was always in conjunction with what he believed in and was inspired by. “He loved the process of creation, be it a pot, a song, a sari or a storybook for children. The process and thought was important for him as much as the final product. This is what I have learnt from him — artist, cultural anthropologist, teacher, designer. The Gandhian in him evoked his simplicity and minimalism in all his acts,” he said.

Cultural historian Jyotindra Jain teamed up with Haku in the late ’70s for the book Temple Tents for Goddesses in Gujarat, India (1982). He remembered his experiences of working with the veteran artist, who helped him chronicle the folk deities, painted on textile pieces in Gujarat-based kalamkari. They would visit Ahmedabad and Haku would soon develop a rapport with the artisans and notice even the smallest possible detail of a dye used, or how a line or a goddess was drawn. They would wake up at 2am to see the rituals around which these paintings were done. Haku would notice something and search for any piece of paper to make his notes. Sometimes from his pocket he would pull out a bus ticket. “Later, I saw there was a stack of these bus tickets, with his fine observation, included in the book,” recalled Jain.