This month, the World Wide Web turned 20, and its birthday was celebrated the world over. It was a pleasant change since the medium, once a new frontier of hope, has been regarded with suspicion ever since the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke. We had spent years outraging over the possibility that our choice of washing machines and underwear was being conditioned by smart web advertising, and, in 2018, we learned that even voter choice was open to manipulation. That marked another anniversary — the silver jubilee of feeling small, lost and sandbagged by the internet. Because before the web, the net was full of command-line cowboys and cowgirls, most of whom had just come online, and were very hopeful and a little lost.

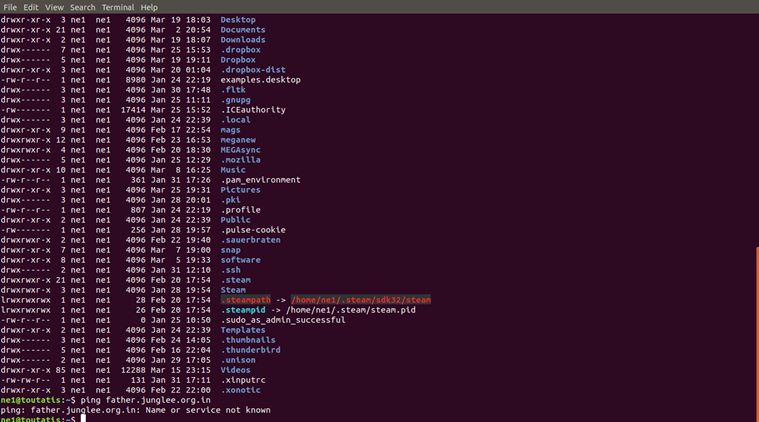

Twenty-five years ago, before the visual web, which is like a picturesque window onto the internet, there was the internet itself in its raw, minimalist beauty — the beauty of the blank command line. It was beautiful if you knew what to type into it, and magically, a server on another continent would respond to your UNIX command. The command line is what Indians saw when they first accessed the internet in the mid-Nineties, with ordinary phone lines and modems with lots of flashing lights. If you were hip, it was a 14.4 Kbps modem. If you weren’t, it was just 9.6 Kbps — in contemporary terms, about the speed of an incredibly slow Torrent that would take two weeks to download a pirated film. It was the era of internet evangelism in search of critical mass, led by personalities like Miheer Mafatlal (now indistinguishable from Merlin), Shammi Kapoor (then at home at father.junglee.org.in) and Vijay Mukhi. It was also the era of common folk who could not even afford an internet connection, and instead dialled into private bulletin boards to chat, download software and access email, the killer app of the internet for over a decade, until the birth of social media. People chatted and mailed a bit, and hardly ever surfed with the now-forgotten Netscape Navigator, whose genetic code lives on in Mozilla Firefox. Surfing was excruciating training in Zen patience, since download speeds of one byte per second were sometimes reported.

The archives of Pew Research reveal that even before the web became mainstream, net use was growing 10 per cent every month. Even in the days of the command line, the online world was teeming with newbies, who were feeling their way. Twenty-five years later, the world is again full of noobs, who do not understand how their data is being used by social media. It’s exactly as it was 20 years ago, except that public sentiment is bleak and no evangelists are putting their heads over the parapet.

In another curious aspect, life online remains exactly as it used to be — humans retain an appetite for creating closed societies exactly like real places. One would have expected them to be utterly novel, breaking out of the rubric of human communities but strangely, we try to mimic traditional communities and geographies. Neal Stephenson was the original oracle in this area with his 1992 cyberpunk classic Snow Crash. Of inconsiderable literary heft, its payload was immense. It depicted an absurd society obsessed with pizza delivery. Among other things, citizens escape this meaningless reality into a shared electronic space called the Metaverse, a community living and playing around a central Strip. There is a strong possibility that Second Life, launched 11 years after by Linden Labs, is inspired by Snow Crash.

Second Life is built on the same mechanics that drive real communities, but you are free to excise the unpleasant parts. People buy and sell, develop real estate, have relationships, perform roles both selfish and altruistic. All they don’t have is inescapable responsibilities. In all other respects, their digital world is more more or less like the analog world.

Now, consider another community that grew willy-nilly, in a space that was created to protect users from surveillance. The Tor privacy network lives in a subspace of the internet that is inaccessible to regular browsers and search engines. It was intended to be a safe haven for people who need protection from surveillance, such as activists and journalists working in the jurisdiction of repressive regimes. It became notorious when people opened a marketplace inside it, selling contraband goods and services like hard drugs and guns. Personally, I was most irritated to find that an east European assassin was charging top dollar to target a leading politician in any country, but offered a huge discount for the life of a newspaper editor. That unnatural place just had to go. And it went, when the FBI infiltrated it. Isn’t it odd that a space designed to be a safe haven from the world was compromised because some people used its cover for a real-world human activity — the art of buying and selling?

Pratik Kanjilal lectures a surprisingly tolerant public on far too many issues.