Meet the real chowkidars: No hashtags, only hardships

Paras Singh | TNN | Updated: Mar 28, 2019, 07:33 IST

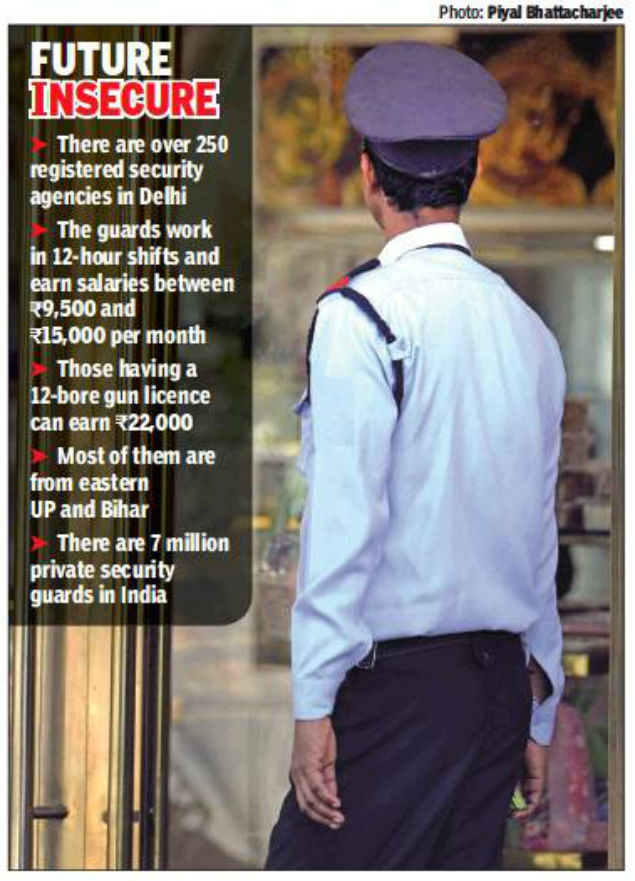

Most of the security guards in Delhi come from small towns in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

NEW DELHI: For Mahesh Kumar Vishwakarma (45), the day starts before dawn. It takes him two hours to cycle from home in Deoli to his workplace at Green Park, so he has to start early. He is a security guard at a bank ATM — a chowkidar — and the long commute isn’t his only worry.

Vishwakarma earns Rs 13,000 every month. Using his bicycle saves him around Rs 2,000 in commute expenses. “I spend this money on my children’s education. Rent takes another Rs 3,000 and the household expenses swallow up the rest of my earnings,” Vishwakarma mumbles. “I haven’t been able to save a single paisa after working as a guard 12 hours a day for the past 14 years.”

His only hope now, he says, are his children, aged eight and five, who he wishes will never have to work as a chowkidar.

That’s the kind of tough life that security guards or chowkidars lead.

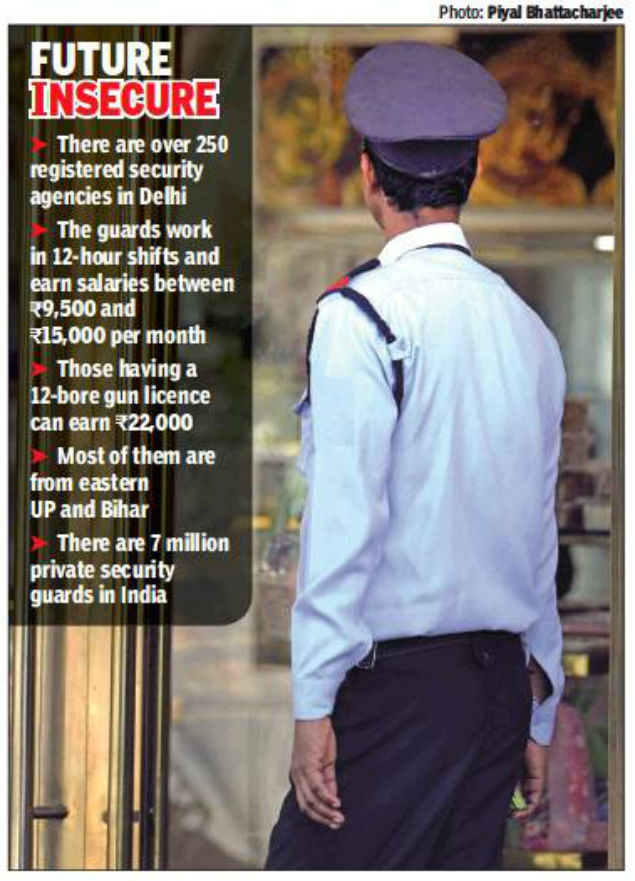

The term chowkidar has suddenly taken on a political colour in election season with netas either adopting it or mocking it. But the fad hasn’t altered the ground reality for the real chowkidars, among the most vulnerable labour groups in the capital. They work 12-hour shifts to protect ATMs, restaurants, housing societies, etc, but get little money and almost no leave.

Ask them what they think about the current political discourse around the term for their employment, and you get amusement, pessimism and even anger in reaction. Down the road from Green Park is Safdarjung Enclave where Mahipal Rawat (51), who was in the Border Security Force for 24 years, earns even less than Vishwakarma: Rs 10,500. He is aware of how exploitative contractors have kept the wages low in his current job sector. He can’t do much about it though. “My children are grown up so I can manage my expenses,” Rawat said. “But imagine surviving on this salary for someone just starting a family. And there’s no regulation. Signatures are often fudged, records are tampered with, but the regulatory authorities are nowhere to be seen.”

Right after demonetisation, these security guards became the public faces of the banking system’s failures, bearing the brunt of public ire for no fault of theirs. They were promised extra money to work double shifts. When the crisis ebbed, they realised they had been taken for a ride. “We were assured of bonus at the end of the crisis, but when things returned to normal, the security companies denied giving us such assurances,” Vishwakarma claimed.

Most of the security guards in Delhi come from small towns in eastern UP and Bihar. Easy gun licences and availability of firearms have made towns like Darbhanga,Mainpuri and Munger the largest sources of manpower for this sector. But with low pay and many mouths to feed back home, these guards go to extremes, even compromising on basic needs, to save money.

Lakshmi Kumar (31) works at a restaurant serving Northeastern delicacies in Green Park. “I sleep at a nearby temple and eat at the restaurant. Of my Rs 13,000 salary, I usually send up to Rs 11,000 to my family in Darbhanga,” he said.

Bijender Singh (46) from Mainpuri, who guards a post office near ITO, also sleeps in office to avoid paying room rent. And for over four years, he has worked two jobs to make some money. “An eight-hour shift at the post office followed by a four-hour shift at an electricity billing counter was doable,” he said. “But the companies increased the shift duration to 12 hours. It was back-breaking work so I had to stop.”

Even though the minimum wage in Delhi is Rs 13,500, the salary of security guards varies between Rs 9,500 and Rs 15,000. Those guarding banks are slightly better off than those on duty at residential colonies and multistorey houses. “Guarding houses is the least paying in the sector,” informed Mahesh Kripal, who works at an upscale locality near Yusuf Sarai market. “We have to stand in rain and sun without supporting infrastructure. Despite this, we get Rs 5,000 less than others.”

Ram Babu (44), Kripal’s counterpart at a neighbouring house, said on paper he gets Rs 28,000, but the “in-hand” pay comes to just Rs 11,000. The contractors fudge signatures to manipulate accounts, he complained. “Why don’t they raid and scrutinise the records of the security agencies?”

The insensitivity of those whose homes they guard adds insult to injury. “Our only point of contact is the agency. Guards get changed after every eight hours. But the residents don’t even offer us a cup of tea,” Babu said.

Can the ‘chowkidar’ discourse change all this? They hope it will.

Vishwakarma earns Rs 13,000 every month. Using his bicycle saves him around Rs 2,000 in commute expenses. “I spend this money on my children’s education. Rent takes another Rs 3,000 and the household expenses swallow up the rest of my earnings,” Vishwakarma mumbles. “I haven’t been able to save a single paisa after working as a guard 12 hours a day for the past 14 years.”

His only hope now, he says, are his children, aged eight and five, who he wishes will never have to work as a chowkidar.

That’s the kind of tough life that security guards or chowkidars lead.

The term chowkidar has suddenly taken on a political colour in election season with netas either adopting it or mocking it. But the fad hasn’t altered the ground reality for the real chowkidars, among the most vulnerable labour groups in the capital. They work 12-hour shifts to protect ATMs, restaurants, housing societies, etc, but get little money and almost no leave.

Ask them what they think about the current political discourse around the term for their employment, and you get amusement, pessimism and even anger in reaction. Down the road from Green Park is Safdarjung Enclave where Mahipal Rawat (51), who was in the Border Security Force for 24 years, earns even less than Vishwakarma: Rs 10,500. He is aware of how exploitative contractors have kept the wages low in his current job sector. He can’t do much about it though. “My children are grown up so I can manage my expenses,” Rawat said. “But imagine surviving on this salary for someone just starting a family. And there’s no regulation. Signatures are often fudged, records are tampered with, but the regulatory authorities are nowhere to be seen.”

Right after demonetisation, these security guards became the public faces of the banking system’s failures, bearing the brunt of public ire for no fault of theirs. They were promised extra money to work double shifts. When the crisis ebbed, they realised they had been taken for a ride. “We were assured of bonus at the end of the crisis, but when things returned to normal, the security companies denied giving us such assurances,” Vishwakarma claimed.

Most of the security guards in Delhi come from small towns in eastern UP and Bihar. Easy gun licences and availability of firearms have made towns like Darbhanga,Mainpuri and Munger the largest sources of manpower for this sector. But with low pay and many mouths to feed back home, these guards go to extremes, even compromising on basic needs, to save money.

Lakshmi Kumar (31) works at a restaurant serving Northeastern delicacies in Green Park. “I sleep at a nearby temple and eat at the restaurant. Of my Rs 13,000 salary, I usually send up to Rs 11,000 to my family in Darbhanga,” he said.

Bijender Singh (46) from Mainpuri, who guards a post office near ITO, also sleeps in office to avoid paying room rent. And for over four years, he has worked two jobs to make some money. “An eight-hour shift at the post office followed by a four-hour shift at an electricity billing counter was doable,” he said. “But the companies increased the shift duration to 12 hours. It was back-breaking work so I had to stop.”

Even though the minimum wage in Delhi is Rs 13,500, the salary of security guards varies between Rs 9,500 and Rs 15,000. Those guarding banks are slightly better off than those on duty at residential colonies and multistorey houses. “Guarding houses is the least paying in the sector,” informed Mahesh Kripal, who works at an upscale locality near Yusuf Sarai market. “We have to stand in rain and sun without supporting infrastructure. Despite this, we get Rs 5,000 less than others.”

Ram Babu (44), Kripal’s counterpart at a neighbouring house, said on paper he gets Rs 28,000, but the “in-hand” pay comes to just Rs 11,000. The contractors fudge signatures to manipulate accounts, he complained. “Why don’t they raid and scrutinise the records of the security agencies?”

The insensitivity of those whose homes they guard adds insult to injury. “Our only point of contact is the agency. Guards get changed after every eight hours. But the residents don’t even offer us a cup of tea,” Babu said.

Can the ‘chowkidar’ discourse change all this? They hope it will.

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE