A Salman Khan release is nothing short of a carnival at Chandan cinema. The night before the big release, members of Salman Khan fan clubs troop in to decorate the theatre in Juhu, Mumbai with balloons, flowers, ribbons and posters. Before the first show, a live band plays hit songs from the actor’s films. Once the movie begins, one can barely hear what is happening on the screen because of all the hooting and whistling. When Bhai enters, of course, a roar goes up.

Priya Mahajan, 27, a member of one such fan club, recalls being a part of this frenzy. “In 2017, I went to Chandan on the eve of Tiger Zinda Hai’s release with my group of friends to decorate the theatre as though it was Salman’s birthday the next day,” she says. But when Khan’s film Bharat releases on Eid in June, the single-screen might not be around. The owners of Chandan cinema, Sameer Joshi and the Wadhwa Group of realtors, have signed a deal to develop the premises of the 45-year-old theatre into a retail and commercial complex with three miniplexes.

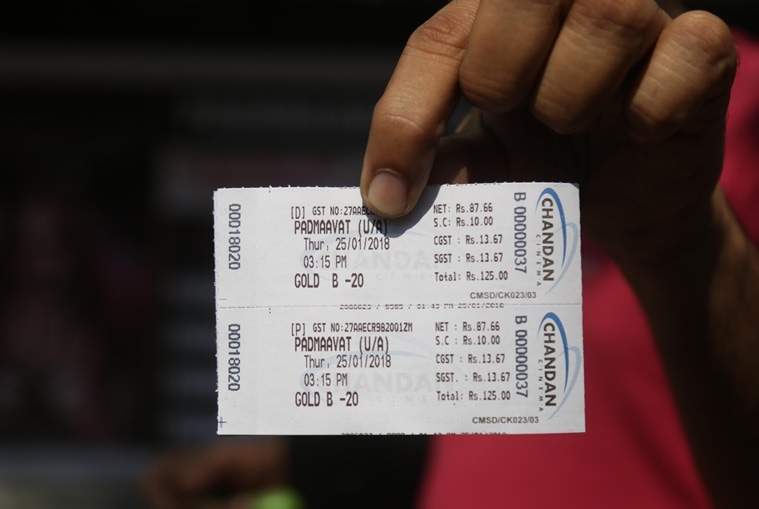

Single-screen theatres in the city have been dwindling in number — many like Milan, Metro, Bahaar, New Empire and Deepak have either shut down or made way for multiplexes. Chandan thrived for a while, even when PVR opened a multiplex in the adjacent building in 2006. With day ticket prices as cheap as Rs 80 and Rs 120 for stall and balcony, respectively, and Rs 110 and Rs 150 for the evening shows, watching a movie here has been a steal. The owners now say they want to improve the viewing experience, as well as their finances. “I want to make it a 5-star experience for the audience. Right now there is just one screen, we can look at better financial prospects if we add more screens as well as some retail chains here,” says Joshi.

The story of Chandan has all the dramatic elements of a Hindi film story. Baijanath Joshi was a businessman in the early 1970s. His wife Chandrakanta, who he fondly called Chandan, was a movie buff. They would religiously watch every Friday release. One week, they could not get tickets to a film. Chandrakanta was extremely upset. Her husband could not see her heartbroken, and decided that he would build his own theatre. He bought a plot in Juhu, got an architect on board and started construction. Chandan opened to the public with the premiere of Raj Kapoor’s Bobby (1973). “If you see the premiere pictures, you will see a little boy standing right in front of Raj Kapoorji. That was me,” says Joshi, Baijanath’s son.

Bobby ran to packed houses at the theatre for several weeks. Joshi recalls the time Sholay released in 1975. “The queue started at the theatre and ended at Juhu gali almost 2 km away. People came as early as 5 am to book tickets,” he says. The theatre that started with a capacity of 1,265 seats was also one of the first suburban theatres to showcase English films.

Single-screen theatres began shutting down during the early 1990s. When Joshi took over in 1994 with the release of the Madhuri Dixit-starrer Raja, the scenario was challenging. Joshi says, “VCR and cable television had killed cinemas. But it was Hum Aapke Hain Koun (1994) that brought the audience back.” He realised that if Chandan had to survive, he had to jazz it up. He got the seats revamped, air-conditioners installed and gave the theatre a makeover.

For the longest time, it was believed that if a movie passed the Chandan test, it would be a superhit across the country. Film exhibitor Akshaye Rathi, who also spent most of his college years watching movies at Chandan, agrees. He recalls the time he watched four back-to-back shows of Dabangg (2010) at Chandan. “Every single time it was a new experience. Every person in the stall got up and started waving their belt to the title track,” he says.

Bhavesh Raja, who has been a consultant manager with Chandan since 1996, says that sometimes it is easy to tell that a film will do well when a phrase catches on. “After Singham (2011), I could hear the crowd repeating Ajay Devgn’s dialogue ‘Aata maajhi satakli’ right outside the theatre.” Similarly, most anticipated films like Raavan (2010), Jab Tak Hai Jaan (2012), Thugs of Hindostan (2018) have failed to please the crowd at Chandan.

“We have to all move with the times. We have the memories to fall back on and cherish,” says Joshi. But he promises us that the efforts to retain the name of Chandan are on. After all, a lot’s in a name.

Priyanka Pereira is a writer in Mumbai

This article appeared in print with the headline ‘Curtain Call’