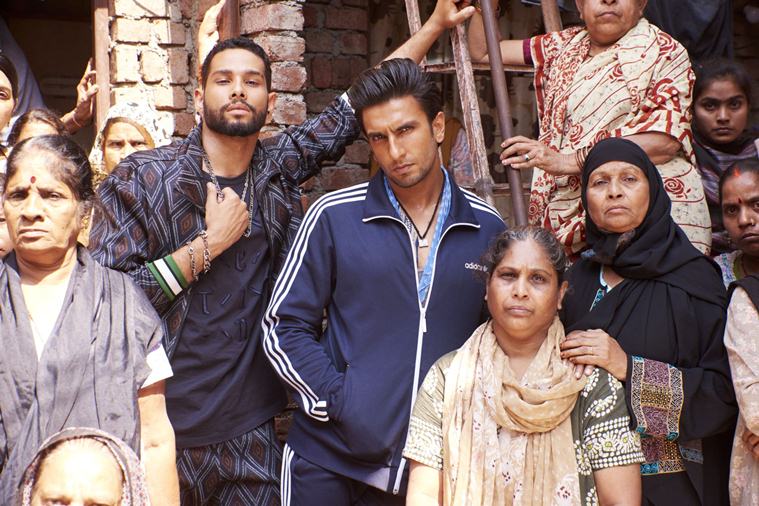

His head is cocked to one side and the visor of his baseball cap is at an angle with his sharp jawline — Pawan Sauda aka Maze 022 doesn’t look impressed by my question. “In Gully Boy (the Zoya Akhtar film that released last month), there’s a scene where an American tourist meets Ranveer Singh’s character, Murad, inside his one-room house, and they bond over Nas. Does that stuff happen? Do tourists pay families to see the insides of homes in Dharavi?”

We’re sitting in a café opposite Mahim station and there’s the slightest pause before the 23-year-old rapper-cum-tour guide straightens up in his chair to answer. “If you watch a movie about Spider-man, does that person really exist? It’s a movie, they added a little spice to it,” he says, before adding, “But the reason people will remember such a scene is not just because Ranveer raps for the first time, but because it shows you that somebody from that background, my background, has no qualms in showing off their home for money like that. Now, do you think anybody will think twice if somebody paid to see a rich man’s home in a different part of Mumbai? But no offence taken, it’s just a movie.”

In the decade between two hit films, Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire (2008), which put Asia’s largest slum on the global tourist map, and Gully Boy, a protagonist-centric success story for desi hip-hop, Dharavi has constantly been wresting control of its narrative. And armed with smartphones, self-awareness and homegrown pride is an unlikely character who is at the frontlines of this struggle: the slum tour guide.

“Hello! How are you? Where you from?” The voice appears to come from somewhere on the left side of the road; it belongs to a stud who’s straddling his bike in a way that would make a young Ajay Devgn blush. It is 5.15 pm on a Thursday, the Mumbai summer has been baring its fangs all week, dousing us in sweat, but he wears a crooked grin on his face, and not a hair is out of place. “Madam, don’t mind, he’s just being friendly,” says Mohammad Sadique, in a single breath, waving at the man, who waves back. Working as a tour guide in Dharavi, the 25-year-old knows that perception is everything.

We take a left turn from under the incomplete Mahim-Dharavi skywalk, and the road becomes narrower still. Piles of plastic in huge bags flank both sides, there’s a sound of metal being crunched not far from where we stand, and there are workers everywhere; some of them smile at Sadique, they are seeing him for the second time today. “Even today, there are tourists who want to see the alley where the chase sequence in the beginning of Slumdog Millionaire was shot. Ganda dikhaya, pura aisa nahin hai (They showed the filth but it’s not all like that). Almost everybody arrives with a preconceived notion about what a slum is about: naked children running around, gangsters, miserable people. As a local, and as a guide, my job is simple: I will show you the Dharavi I know, the people I know, and you decide how you want to see it,” he says.

Originally from Darbhanga, Sadique’s family has lived and worked in Dharavi for the past two generations, but the 25-year-old tailor’s apprentice never imagined that he would be showing foreign tourists around the slum. “My family is extra-large: I am the youngest, with seven sisters before me. It wasn’t possible for my father to give me a good education. But all I wanted was to be able to speak English confidently,” he says. About seven years ago, Sadique noticed an American tourist in his neighbourhood. “I wanted to talk to him, but white people don’t talk to strangers. So, I followed him,” he says. The American tried to shake him off, but finally relented and asked him if he was a local.

“I spoke very little English, but when he asked me to show him around, I jumped at the chance. I took him to my friend’s house, my neighbours’ houses, every place I could think of, and, at the end of it, he was very pleased. He told me that I should think of becoming a tour guide for Dharavi. All I had was a basic cellphone, so he accompanied me to the local cyber café and created an email address for me,” says Sadique. A few months later, a review of Sadique’s on-the-spot tour appeared on the Lonely Planet website. Overnight, his phone began to ring, and his inbox was flooded with requests. “I’ve been very lucky — one guest taught me how to make a Facebook page, another designed and printed business cards for me,” he says. When Sadique started his one-man company, Inside Mumbai Tours, in 2012, he joined other local players such as Be The Local (run by Dharavi students working to fund their higher education), SlumGods (a hip-hop collective that offers tours) and Mystical Mumbai (who take you to the areas where films set in Dharavi have been shot). “I still don’t like Slumdog Millionaire, but nobody here can deny the fact that it’s been good for business,” he says.

Boyle isn’t the first foreigner to come to India to shoot a story about the urban poor. In 1968, French filmmaker Louis Malle made a seven-part documentary series for the BBC, called L’Inde fantôme: Reflexions sur un voyage (Phantom India), which attracted the ire of the then government, who protested the way in which the country had been portrayed. “Poverty porn” hadn’t quite entered pop-culture lexicon then; the word first showed up in the 1980s. Dominique Lapierre’s City of Joy (1992) was set in a Calcutta slum and was criticised for promoting the “white saviour complex”. But some films do get it right — Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay (1988) is an absolute triumph in the same way it humanises the street children who live in the slums of south Bombay, as Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund’s Cidade de Deus (City of God, 2002) does with young people in the crime-stricken favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

In 2002, Chris Way, a British national, was volunteering at a local slum school in Mumbai. Having lived in Rio a few years before, he wondered if slum tourism, an industry that propagates giving back to its residents, was possible in Maximum City. Three years later, he co-founded Reality Tours and Travels, and in January 2006, it became the first company to offer slum tours in Dharavi, at Rs 300 per head.

In an origins story that lends itself to a screen adaptation, Way first met his Indian business partner, Krishna Pujari, at a Colaba restaurant: the latter, the son of rice farmers in Karnataka, was his server. The same week, they met at the Oval Maidan, during a game of cricket, and struck up a friendship. “When Chris told me his idea, having seen slum tours during his stay in Rio, I didn’t see how it could work. So, I visited Dharavi several times, and saw that it was more than a slum; I wanted us to share that. But I had a hard time convincing the locals that they would benefit from the tours. They thought I was showing the foreigners ‘poor and hungry’ India,” says Pujari, who kept returning to Dharavi to talk to its residents, and explain how an ideal slum tourism model would work.

In 2009, their NGO, Reality Gives, was founded and 80 per cent of the profits from the tours is directed there — the organisation provides computer skills, extra-curricular and empowerment programmes to youth in Dharavi. Today, Reality Tours offers over six kinds of tours set in Dharavi, including an express tour (Rs 600 for 90 minutes), the standard one (Rs 900 for 180 minutes), a cooking tour as well as a street-art walk, among others. “It’s a little more expensive than the other tours, but I think it’s worth it because at the end of the tour, they take us to the schools they have partnered with. I can see where my money has gone,” said a Welsh tourist.

It’s a tricky industry, says journalist Kalpana Sharma, author of Rediscovering Dharavi (2000), not only due to Dharavi’s status as a semi-legal settlement, but also because of the moral ground slum tourism occupies. “These initiatives force us to address our perception of how the urban poor should live, whether or not they should make the most of their circumstances. What is Dharavi about? Enterprise and survival despite the state,” she says.

Every local who works as a guide will impress upon you that here, both space and poverty, are relative. “Each tour begins with a walk through the industrial areas — we want to dispel the notion that the lack of infrastructure is equal to the lack of industry or commerce. The recycling business generates crores of rupees; after exporting their produce all over the country, Dharavi’s leather factory started their own brand, Love Dharavi. Taqleef hai, lekin mehnat bhi (There is hardship, but also hard work). People here feel proud that they’re able to earn an honest wage,” says Sadique. The most difficult aspect of working as a guide, he says, is not the repetitive nature of the tours, or language barriers — it’s that most people don’t think that it’s a job.

“Anybody who thinks that I’m ‘selling my poverty’ can take a walk. The locals know how we’re contributing to changing the perception of this slum,” says Sauda, who gives his earnings to his grandmother after keeping aside a little to fund studio time for his music. Raised by his aunt and grandmother in Matunga Labour Camp, near Sion, Sauda worked a number of odd jobs before joining the tourism industry. Sauda isn’t keen to talk about it, but he turned down a small part in Gully Boy. “I was asked to act in a rap battle scene, where I would have to lose. I know it’s a film, but I cut my teeth in battles with the first generation of Dharavi rappers — I have what it takes to win,” he says. It’s easy to mistake his confidence for arrogance, but for somebody whose time is yet to come, the decision is as political as it is personal. In the meantime, the hustle continues: he’s wrapped up one photography tour of the slum, and he’s heading to another in an hour.

Like most guides, Sauda charges between Rs 500-1,000 for a tour, depending on the number of people. Tours usually begin at 9-10 am, and guides prefer to do an average of two trips a day, with each tour lasting between two-three hours. “October till March is the season. A monthly salary is anywhere between Rs 15,000-20,000, depending on the number and types of tours you conduct,” says Shailendra Pandey, 23, of Dream City Tours. He joined the industry while he was still in school, to help pay for his father’s medical treatments, but stayed on to learn the ropes. After seven years of working for other operators, he recently struck out on his own.

“Have you been to Central Park, NYC?” asks Nilesh Vaidya, after he gathers his five-member group of German and British nationals at the starting point of every slum tour — the foot-over bridge between Mahim and Dharavi, a vantage point for the first glimpse of a sea of blue tarp covering shanties and tenements on the “wrong” side of the tracks. Some nod yes, others shake their heads. “Dharavi is home to 1 million people who live in an area that is two-thirds the size of Central Park. Most neighbourhoods within boast of 24-hour electricity, but running water is only available for three hours a day. However, there are supermarkets, clinics, temples, mosques and churches. This is a community,” he says. After stopping by the leather-processing section, the group takes in the smell of khari biscuits that waft from a basement bakery, and the sight of a man vigorously soaping himself in the community washing spot. If anybody is shocked, nobody shows it.

Their faces don’t stay quite as impassive after the 27-year-old Reality Tours employee disappears into the labyrinthine lanes that snake through parts of the residential colony. Vaidya must move swiftly, and so must they, for only one person can pass at a time. Occasionally, a curtain is drawn aside from one of the rooms, a snatch of a song from a cellphone travels through the corridors of this haphazardly-built structure. When the group gathers in the courtyard of Kumbharwada, the potters’ colony, there’s an audible sigh of relief. Questions are raised about the history of the settlements, the number of religious communities living cheek by jowl, the government’s involvement in providing better infrastructure. Vaidya tells them about the dilemma regarding the 2004 Dharavi Redevelopment Plan, how it won’t result in equal housing opportunities for the residents.

“He’s told you the plot of Kaala!” says Sadique, later, quietly chuckling for a few seconds, before adding, “He’s not wrong to refer to that film — it’s the most accurate representation of present-day Dharavi in anything we’ve seen.” Starring Rajinikanth, the action-drama explored the corrupt practices of those engaged in slum eviction and redevelopment schemes. Kaala, too, had toyed with introducing a tour guide as one of the characters. “We’d written a scene where we were taking a slight dig at the slum tourism industry. But it didn’t come through well enough, and the last thing we wanted to do was impose our perspective on people who live and work here,” says Jenny Ruban, associate director of Kaala.

In the early days, before the tours became a daily feature of their lives, the locals weren’t quite aware of how to handle tourists’ attention and unabashed curiosity. “Some guests would request me to take them to my home, so I did. My grandmother didn’t appreciate having to suddenly entertain extra people in our single-room flat. So, there are rules now. We don’t allow tourists to enter homes on a whim, or to take photographs without permission,” says Sauda. Tourists are treated to a smile, but nobody really has time for a chat, not when a million chores must be completed. The only people enthusiastic about tourists are school children. You know there’s a tour in progress when the sound of “Hi! Hello!” echoes through the lanes.

To make up for my first question, I ask Sauda another one: if he could visit any part of the world, where would he like to go? Pat comes the answer: “America. It’s the birth place of rap and hip-hop. I want to see what that’s like.”

“Switzerland. Every romantic film of the ’90s was shot there, how can I not go?” says Pandey. Finally, it’s Sadique’s turn and he takes a moment to speak. “I never thought I’d ever sit inside a cafe. When I saw tourists visit the slums, all I ever wanted was to be able to speak to them in English. I don’t know where I want to go first, but for now, it is enough that the world is coming to my doorstep.”

This article appeared in print with the headline ‘ A Mouthful of Sky’