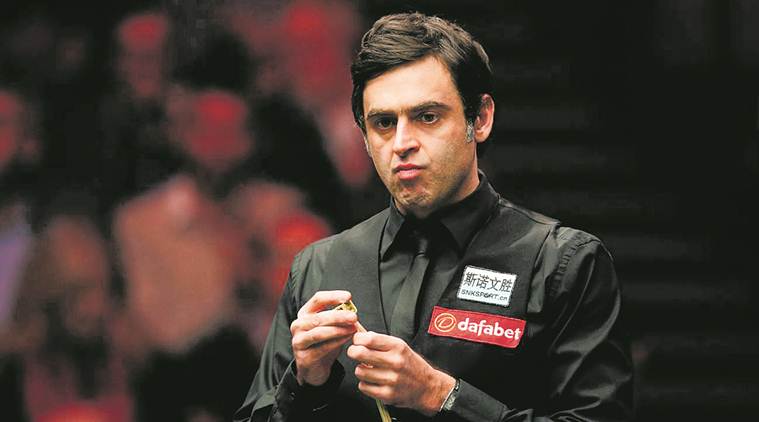

Sports montage-makers often opt for the Chariots of Fire theme to accompany a rousing build-up to a sporting crescendo. In India, nothing is glorious until Chak De! blares out to go with the collage. So it’s interesting when a Charlie Chaplinesque soundtrack lends itself to the fast-forwarded video of snooker champion Ronnie O’Sullivan on his way to reluctant-perfection.

Reluctant, because all through the winning frame in Round 2 of the 2010 World Open against Mark King, the English legend is carping about how there’s no extra bonus for getting to the maximum score of 147. He stops play to ask the referee if there’s a top-up to the £4000 that the highest-break will earn. He makes a face when the ref says there’s none – all of it watched by the bewildered King. Ronnie’s effectively threatened to not pot the last black, but the goading referee Jan Verhaas has at some point talked him into going for it. O’Sullivan goes about his business — painting the canvas as only he can with angled strokes and splashing colour into pockets. Wrapping up his 10th televised “maxi” of 147, he then proceeds to make life miserable for the star-struck post-match TV presenter. He leaves in his wake King, who’s spent a bulk of the match sitting bemused through Ronnie’s antics with an outstretched hand trying to congratulate the 3-0 winner.

That was one of the many moody century-breaks of Ronnie O’Sullivan — he compiled a mammoth 1000 on March, the 10th. This time he was grinning away while approaching the 100-mark, basking in the adoration that the Preston crowd was showering on him, switching hands with a dramatic pause, while getting there potting a red.

There’s perfection in sport that’s laboured — Tendulkar’s crawl to the 100th 100 in Bangladesh. There’s greatness that looks like it’ll elude — Margaret Court’s all-time pickings for Serena Willians. There’s coy, nonchalant attempts at glory too — O’Sullivan’s own pursuit of Hendry’s 7 world titles — he has 5, and he chucklingly pretends it’s no stress if he doesn’t get there, given his dozen retirement announcements, from which he promptly comes back. But in the matter of century-breaks — the 43-year-old has left the second-placed Hendry far behind, at 775, and chased the 1000 with such glee that sport briefly forgot the word ‘pressure’.

***

India’s Aditya Mehta spent 5-6 sessions playing with O’Sullivan last October, when the legend started training at London’s Whetstone Club. Mehta chortles about how a player who has barely 50 century-breaks sees the enormity of someone who boasts a 1000. “Not everyone likes to play Ronnie, and I knew I’m going to get battered everyday for hours. I said ‘fine, let’s play,’ it was fun. I actually won one set! He was also coming back after a long break. He’s pretty chilled, he’ll play anyone, he just wants to play,” he recalls.

It was Mehta’s latest attempt at demystifying the perfection. “We think he’s perfect. But he’s not. It’s about putting yourself in such an area where you have options. It’s actually not that difficult, but you need that click in your head to see those shots. And he sees those shots. It’s just the art of break building. And he is the greatest break builder of all time,” he says in one breath.

Nobody can be perfect on shots, but it’s not about one shot, it’s the concept of break building. “All great break builders will never play on specific balls unless they absolutely have to. They’ll always be developing things. Before you know it everything is developed but they never took any risks because they had the vision to create things when they didn’t need to. That’s the beauty of Ronnie O’Sullivan.” he ends.

The 1000 made it to Guiness Book, it’s got actor Stephen Fry to say it’s been a privilege to exist in Ronnie’s era, it’s given newspapers the opportunity to revisit the enigma and it’s cleaved open the debate if the eccentric genius should be allowed his joyous muck-abouts — the rants against governing bodies, his myriad larks and stunts that never seem to affect his game adversely. “I completely enjoyed when he switched to the left hand, just having fun. I would have been surprised if he didn’t do something stupid. He can hit a maximum with his left hand. I can’t even hit the cue ball straight!” Mehta guffaws.

O’Sullivan’s enjoyed poking with the cue and spat out honest prods with his ceaseless chatter taking on the establishment and lamenting how the prim and proper snooker cares a tosh about players struggling in the lower rungs and not making enough dough to survive. “I’ve spent hours and hours with him. He doesn’t show that to the outside world, but he’s genuinely a nice guy,” Mehta insists.

The Indian’s greatest joy was watching another break-constructing legend Anthony Hamilton decode every move and talk him through how Ronnie went about his art. “When I looked at a match, I’d wonder ‘why did he do that’ and I’d get an answer from Anthony. I could not just watch and be able to tell how he always opened up positions with so many options,” he adds. He doesn’t think there’s method to the madness. “There’s 100 per cent method. No madness.”

Watching crowds watch O’Sullivan — how he buzzes around a table, keeps lipping his inner-thoughts into the ref’s ear, picks a bone with commentators, leaves opponents mesmerised and vexed in equal measure and finally how he polishes off the balls, blacks following reds (and sometimes cheekily not) and others disappearing like a scoop off the cone with a lick — is what fills up snooker arenas. In O’Sullivan’s case, achieving perfection makes news, not-achieving doubly so, with all the theatre that goes with his ‘won’t do, cause he can.’ On his 1000th 100, he sent down a foul so that his opponent, the blond-haired Neil Robertson could pocket the prize for the highest-break which left the latter doubling down, with mouth wide open.

Pankaj Advani, India’s own cue-sport juggernaut, reckons ‘abundance’ is an under-statement for O’Sullivan’s talent. He believes the creative beauty of Ronnie’s positional play though stems from his tough beginnings – which included a parent who was jailed for murder, and battles with alcohol and drug abuse and depression in his early years. “I feel that this game has been an outlet for him to deal with that. To be in a totally different world where he can put all that behind him. It’s contradictory, but you can understand what he is and what makes him such a good player — because of the struggles he’s faced earlier,” Advani says of flamboyance, which like abstract art and an inreplicable painting, literally breaks out like a rainbow in grim skies.

The closest contemporary for Ronnie in terms of century-breaks is at 600-odd, and the 1000 just makes the mark look out of anyone’s reach. “A century-break is not something you can make every single day. The 15 reds will always be in a different place on the table. Where Ronnie stands out is that his rhythm is so beautiful to watch on the table and it’s so in sync with what he’s trying to do,” Advani explains.

The 1000 is hardly about longevity – though 27 years is a long time to survive at magically high levels. The devil-may-care outrageous shots, the risk-taking make him a fan favourite. And the sport, which he is synonymous with in England and China, silently worries about the time he’ll really be gone.

His frequent attempts at retirement might have something to do with his lack of enthusiasm to travel, though the 7 World title mark sure dangles like a carrot. O’Sullivan actually enjoys billiards, Advani says, and gives a peek into a lesser-known fact: the man they call Rocket, abhors flying. “He’s told me ‘I’m sh*t scared of flying. ‘I need the air hostess to put me down in my seat and tie the seat belt all the time. I get very jittery.’ That’s why he doesn’t travel much. Even to go to Germany he takes a train. He says ‘I’ll drive it down but I won’t fly.’ Irony is that his nickname is Rocket,” Advani laughs.

***

Two players who make Ronnie uncomfortable are Mark Selby and Judd Trump. Unlike Selby, grinding and gritting is not his style. India’s first pro Yasin Merchant, a reluctant O’Sullivan fan, adds the name of Peter Ebdon to that list. Merchant who started out with Ronnie on the pro circuit (“At one time, we were both going unbeaten. We were both at 17 matches. I lost the 18th, he lost his 78th!”), insists that the Englishman learnt how to win from a point where impatience used to cause his downfall. “He learnt how to chase titles, how to win, how to take matches and frames away from his opponent,” he says.

What gets Merchant’s goat — besides the fact that Ronnie isn’t Stephen Hendry, his idol — is the antics. “Ebdon takes a long time to get moving and would play with Ronnie’s mind. Ronnie would probably then throw away a frame. Now, Ebdon is bald. Ronnie had a match with him, so he shaved off his head and came in bald,” Merchant says. “It’s not becoming of a snooker player. Ronnie has that attitude: play, or let me play.”

Merchant, who first saw him as an 11-year-old winning a tournament called the Pontins, knew O’Sullivan would go places but also admits he is not his “favourite player”.

“I like to see a champion in totality and for that I look up to Hendry who carried himself phenomenally. (O’Sullivan) gives off that bad boy vibe. At least 15 times he has retired. But he’s got the game to back up his words,” he says, adding, “He’s forced me to become a fan because he’s made the game look so easy.”

Merchant can’t resist a prick to the bubble though. “I may be going out on a limb here, but the pockets were tighter in Hendry’s time. Now since they want to make it a TV sport because people like seeing breaks, so they’ve eased up the pockets a little.”

O’Sullivan post-40 is a different beast because of how much he enjoys his sport. In an interview to Guardian two years back, he had said, “I was just unhappy before. But I didn’t know anything else beyond potting balls… Now I’m happy.” He goes into jungles for reality TV, he runs 10K to keep up fitness, he’s co-written crime novels and worked on pig-farms, and hangs out with one of the greatest modern-day artists Damien Hirst. In snooker, he’s sought help from celebrated mental coach Steve Peters and dipped into SightRight, a coaching technology that’s aided his game. “He is not bigger than the game, but the game needs him,” says Merchant. “He’s retired almost every year, but the day he finally does, it’s going to leave a little dent.”

To Merchant, 1000 break is just consistency, hunger and ability to take the frame away from a guy. “There have been matches when Ronnie has played a 147 but still lost the match. I would say, he would trade his 1000 breaks for the seven world titles.”

What drives Merchant up the wall is when Ronnie O’Sullivan deliberately hit a 146. “Why would you do that? I’m a firm believer in jaisi karni waisi bharni. This one time, I had won the match, last three balls to go, so I thought I’d try some fancy shot. The last black, it flew off the table. (Three-time amateur billiards world champion) Michael Ferreira was the chief guest. In his speech, he said ‘I’m pretty disappointed with the champion of today. This is not how you treat the game that is treating you well.”

As much as administrators like to bring up ‘respect’, players like O’Sullivan, or Nick Kyrgios or Zlatan Ibrahimovic can woo fans with one moment of magic. Ronnie once notoriously passed up a chance at 147 against Barry Pinches, reasoning that the £10,000 prize was “too cheap”. A good night’s sleep and some waving away of social media outrage later, he turned up at a morning BBC TV show. “When you get to 25 years in the sport, you gotta start enjoying it at some point… When you’re in that plane (of focus or zone), you don’t start thinking of (donating money to) charity, about what everybody’s going to say. It’s the only time in whole life when you drop the problems out (of) the door, just go into a wonderful zone out there. I don’t know how it works for everyone else… but things in the head make you want to do things that make you happy. Just a bit of a showman’s high,” he’d recount.

He first used the non-47 to impress Stephen Hendry. “I used to do 140s in practice and deliberatley not put black because its more impressive than to make a 147. Because everyone’s used to people making the maxis. I was only 16 — and Stephen Hendry was watching. So I made a 140, and just set the balls up just do little things and get a laugh and a kick in practice when he watched. I mean I’m sorry to get a kick out of something like that,” he’d explain away turning down the 10 grand. “It’s not about the money,it’s just about having fun, having a bit of a laugh,” he said. “I’ll try not to have fun next time.”