For the past few months, sisters Tahira and Sayeeda have been receiving calls from their family members in Pakistan to approach someone in the Indian government to arrange their travel documents. Their 65-year-old mother back in Karachi is ill.

The sisters live in Kupwara, a border town in North Kashmir. Having returned to the Valley in December 2011 along with their husbands under the J&K government’s rehabilitation policy for former militants, they have not been back since then as they don’t have either passports or travel documents.

A mother of four children, Tahira, 37, says, “We don’t know what to do to get a passport. I want to meet my mother. For more than seven years, I have not met her, my brothers or sister.” Their mother has a spinal disc problem, Tahira adds, and can barely walk.

“Otherwise, she may have tried to come.”

Tears roll down the cheeks of Sayeeda, 36, a mother of five, as she despairs that they may never meet her again.

In 2010, the then state National Conference government had announced a surrender and rehabilitation policy for J&K youths who had crossed the Line of Control to receive arms training. Only those who had gone to Pakistan Occupied Kashmir or Pakistan between January 1, 1989, and December 31, 2009, and their dependents were eligible for consideration.

In 2017, the then state government informed the Assembly that only 377 former militants along with 864 family members had returned from Pakistan via Nepal and Bangladesh since 2010.

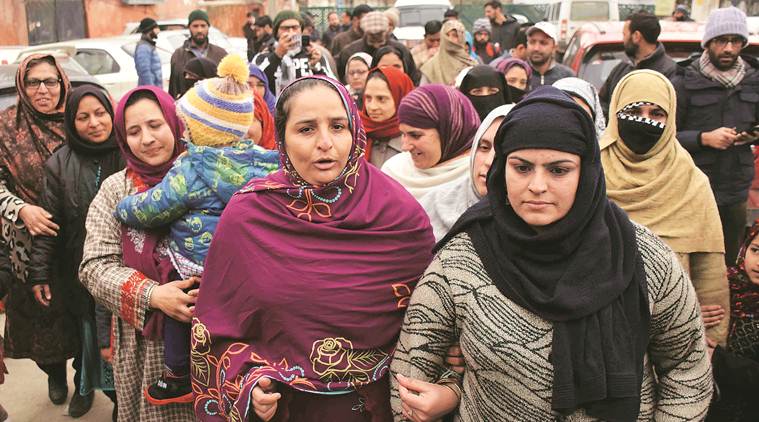

However, even those who returned claim they got neither the promised proper rehabilitation nor a State subject certification. Moreover, they are still struggling to get documents which would allow them to meet families on the other side. In February, a group of women originally from Pakistan staged a protest in Srinagar demanding that they be provided the required papers.

Tahira and Sayeeda say their husbands are friends and crossed the LoC together in the 1990s for arms training. While Tahira got married to Nazir Ahmad in 1996, Sayeeda and Rasheed Ahmad got married a year later.

After the surrender offer, says Sayeeda, “Our husbands decided to return to Kashmir together too. They even thought that if things didn’t turn out alright, they could come back.”

Tahira recalls that another friend, who had taken the rehabilitation offer earlier, convinced their husbands. “He had come to Kashmir with his family before us. He said everything is fine in Kashmir, that it is a proper rehabilitation system,” she says. “My husband’s mother also kept urging us to return.”

On December 23, 2011, Tahira, Sayeeda, their husbands and children left Karachi for Kupwara. Recalling how their mother came to the Karachi airport to see them off, Tahira says, welling up, “She cried so much. She kept telling us not to go, that we will regret our decision. Today, we realise she was right.”

They took a flight to Nepal and then a bus and train before reaching Kashmir on December 27.

The sisters say it was tough adjusting to their new life. “All our relatives are there. During festivals, especially Eid, I would go see them. Here, my husband’s relatives had kept asking us to return, but only 15 days after we came, our relations with my in-laws started worsening. We had to move into a new house,” says Tahira, adding she also found it difficult to cope with Kashmir’s harsh winters. “In Karachi, we never had such cold.”

It has also been difficult explaining to their children why they can’t travel to Pakistan. “My children keep asking me why we can’t go see our relatives, like their friends visit their families here. My children also want to meet their naani (grandmother). Danish (her elder son) was attached to her.”

While the sisters do talk to family members in Pakistan over WhatsApp, this is often not possible for days together as Internet is snapped in the Valley.

The Srinagar protest gave Sayeeda and Tahira new hope of the government conceding their demand. “It (the protest news) circulated on the Internet, came on TV channels in India and Pakistan,” they say.

But even they know the Pulwama attack and India’s aerial strikes on Balakot have pushed that possibility back. Mehtaab, who is also from Karachi and returned in 2012 under the rehabilitation policy with husband Fayaz Ahmad, could not see her mother before she died. “Doctors had informed us in advance that she would die in two months. I applied for a passport, but I couldn’t get it,” says the 50-year-old.

Mehtaab went into depression. “I am taking the highest dose of medicine even now…,” she says. “We can see our loved ones alive or dead only on mobile phones.”

Fayaz says their children’s lives too are getting affected. “Two years ago, my daughter cracked a medical entrance and I wanted to send her to Bangladesh. Those students who scored lesser are studying in Bangladesh now, but my daughter couldn’t go.”

In the recent panchayat elections, at least two women who returned to the Valley after 2010 tried another route: they joined the poll fray. However, Dilshada Begum, who was elected sarpanch unopposed from the Prangroo Kalamabad area in Kupwara district, says it hasn’t helped.

Residents of Kupwara, Dilshada’s parents had crossed over to PoK in the early 1990s. There she married Mohammed Yusuf, a resident of Kupwara who had crossed over for arms training in 1997. In 2012, the family returned to the Valley though Nepal. A disheartened Yousuf says, “If we came with our wives and children, why doesn’t the government allow them to meet their family members on the other side? Is this what we have got in return for trusting the government?”

The government is now looking at reviewing the rehabilitation policy. K Vijay Kumar, an advisor to J&K Governor Satya Pal Malik, told The Indian Express recently that they would submit a report after consultation with all concerned.

As for the problem of the women who came back on an earlier promise, no official is ready to come on record. A senior officer said it is a “humanitarian problem” and they are trying to come up “with some kind of relief”.

But Tahira and Sayeeda don’t have time on their side. As India-Pakistan relations worsen, their last window to see their mother may be closing, they fear. Says Sayeeda, “They tell us we are Pakistanis and can’t give us anything. I guess it is our fault, for being a Pakistani.”