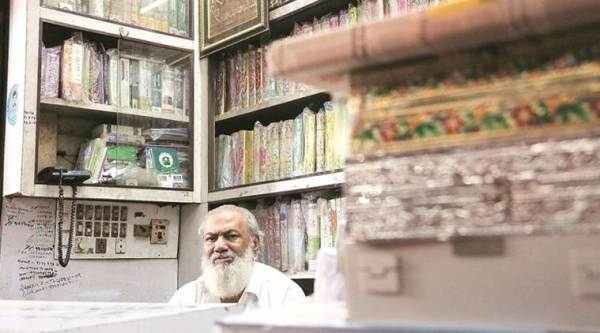

At 74, Fazal Ahmed Shad’s memory has started fading. But the Sunday of January 9, 1993, remains fresh. From his bookstore counter, a gnarled finger points across South Mumbai’s cluttered Mohammed Ali Road to where Suleman Usman Mithaiwala Bakery stands. “I was in J J Hospital morgue helping families identify their dead relatives in riots when police fired there,” he says.

Twenty-six years later, as the trial into the firing, that led to the death of nine Muslims, has finally begun, for Shah, the case is already over.

“Nobody is interested. We lost eyewitnesses, evidence,” he says, hinting at the missing police log book, that had wireless call records between police and the control room when the bakery was attacked. On March 1, the prosecution informed the Mumbai City Civil and Sessions Court that it is untraceable, while on February 13, the day the trial began, the first witness had turned hostile.

Shad talks about the effort it took for him to convince witnesses to record their statements during the judicial inquiry. “But the government delayed the case. Now no one wants to relive those days. I have also stopped following it.”

On that Sunday afternoon, in the midst of Mumbai riots, police officers and a Special Operations Squad had opened fire at Suleman Usman bakery, the Dar-ul-uloom Imdadiya madrasa located above it and the adjacent Chunabatti mosque, claiming a tip-off that there were rioters inside the building. Apart from the nine who died, 12 were injured in the firing. At least 78 people from the bakery were taken into custody.

The Justice Srikrishna Commission that inquired into the 1992-1993 Mumbai riots found no basis for the police claims in the case: “The evidence on record in no way bears out the police story that there were terrorists, much less with deadly arms; nor does the evidence suggest that it was necessary for the police to carry out such extensive firing.”

Shad’s Universal Book Depot, that sells books on Islamic texts, is located opposite the bakery. “I saw that madrasa every day. They were innocent. I wanted to do what I could to bring justice,” he says. As secretary of the Mumbai Aman Committee, which had opened a helpline for riot-affected victims, he encouraged witnesses of the incident to approach the Srikrishna Commission.

“Most were reluctant, after all it was a case against police,” Shad’s son Shehzad Faisal says. His younger son, Ayaz, adds, “We would get threat calls from unknown persons.”

Maulana Abul Wafa, Maulana Noorul Huda and Mohammed Farooq Shaikh were few key witnesses whose statements were recorded after Shad coaxed them. While Huda passed away in 2012, Shaikh (the panch witness) turned hostile on February 13 and Wafa has decided to stay away from the case.

Wafa (45) was a student at the Dar-ul-uloom madrasa. His teacher Maulana Abul Qasim was among those who died. Recalling how they “started running when police entered and fired”, he falls silent when asked why he does not wish to depose. After a moment, he adds, “So many years have passed. What will we get by remembering?” Wafa is now a teacher of Islamic texts.

The first to be examined in court, Shaikh maintains he does not recall anything. Three years after the Srikrishna Commission report, in 2001, a Special Task Force had registered a case under Section 302 (murder) against 18 police officers, including former Mumbai commissioner Ram Deo Tyagi, who was a joint commissioner in 1993 and led the firing. Shaikh’s statement was recorded then.

Sitting at his footwear shop now, located next to the Salman Usman bakery, Shaikh says, “Agar koi mazboot aadmi sar par hota, to apan fight bhi karte (If I had strong support, maybe I would have fought).”

Shaikh used to sell footwear from a cart on the street outside the bakery when the incident happened. He was made a panch witness (an individual unrelated to the crime, who is called by police to authenticate the crime scene) eight years later.

Noorul Huda, a teacher at the madrasa from Uttar Pradesh, who was injured in the firing and named an accused, hung on to hope for a long time. After Tyagi and eight other police officials were discharged, and the Maharashtra government did not challenge the discharge, he appealed.

But the discharge was upheld by the high court and, in 2011, by the Supreme Court. Months later, in 2012, Huda passed away.

While the Srikrishna Commission had recommended action against Tyagi, senior advocate Vijay Pradhan, who represented Huda in the Supreme Court, says the police officer was discharged on the grounds that he did not fire any bullet. Pradhan emphasises that police fired at close range, and cites the postmortem report showing all nine men were shot in the back, suggesting they were trying to flee, contrary to police claims that they were confronting them.

The next hearing in the case is on Monday, March 11. “This is a sensitive case. I cannot comment on the witnesses who are scheduled to depose,” says Public Prosecutor Ratnavali Patil.

From 1993 till 1998, Shad says, he went to 47 police stations looking for missing Muslim men and helping families relocate them. He would hold meetings with locals to encourage them to record statements of police atrocities. He had his wife, three sons, and his old father to support at the time. “I would leave my father at the shop and go meet witnesses. I had confidence that if the community collectively pursued, justice would come.”

But his hopes dwindled when governments changed and the Srikrishna Commission’s recommendations remained ignored, he says.

At the bakery, 1993 is discussed in hushed tones. There were 30 labourers on the day police opened fire, owner Abdul Sattar Suleman Mithaiwala Sattar says, adding he bailed out several of his men. Among the nine who died were five of his labourers. A sixth labourer remains missing still.

But neither did he wage a legal battle against police, nor were the poor families of the labourers capable of doing so, Sattar says. “Those who did rioting here were policemen. Will police provide proof against its own?”

However, something did change. “There is an English saying I have started believing in. Justice delayed is justice denied,” says Sattar.

“Now we say it was an accident.”