At times, a blade can do what a rifle cannot. It’s match-day minus two of the World Cup. Or as the shooters call it, equipment control – a pre-tournament test to ensure all their paraphernalia meets the prescribed standards. Samresh Jung saunters into the 10m qualification hall of the Dr Karni Singh Shooting Range, looking amused as he peeps into a room in the centre of a narrow corridor.

It’s a long queue of jet-lagged, anxious shooters waiting to get their gear checked. Some are filling up a white form with boring efficiency, a giveaway that they’ve been filling the same form for years. Most fiddle with their phones while a few visibly tense athletes are tearing their clothes apart. “You sit there and see people do all kind of stupid things,” Jung says.

Not so long ago, he was a part of this queue doing the same ‘stupid things’ – if not for himself, then his teammates. One time in Hannover, the former Commonwealth Games champion landed at the shooting range with a hair dryer and a blade, two most unlikely weapons in his array of armour. They were for Gagan Narang, whose shooting jacket wasn’t passing the equipment control. “When we left, it was summer time in India while in Germany, it was winter and raining. Because of the change in weather, the jacket got thicker and stiffer,” Jung says.

To bring the thickness under the International Shooting Sport Federation’s (ISSF) pre-decided limit, Jung and then India coach Lazlo Szucsak got their blades out and started tearing it up. “We took blades and were cutting it so that it became flexible enough to pass the test. The three of us were literally hammering it, trying to break it,” Jung says, breaking into a somewhat hysterical laughter.

Shooters are unique. A Lionel Messi can slip into a goalkeeper’s jersey and continue to be jaw-droppingly good. Virat Kohli can pick a half-decent bat and still whack a few out of the park. Rafael Nadal will chase down every ball even if his shoes aren’t exactly snug.

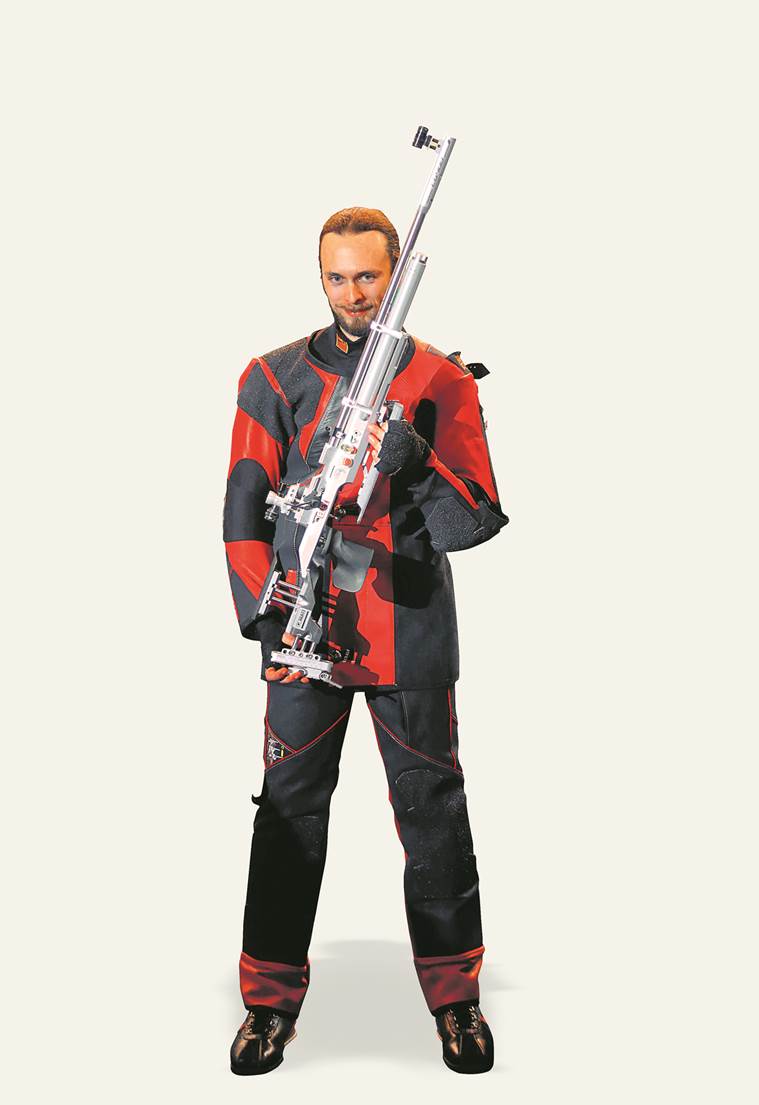

But not shooters; they are a different breed. In their quest for perfection, everything is heavily personalised. More so in rifle, than pistol or shotgun. No two jackets are the same, the shoes are custom-fit and even though there are rare occasions of them borrowing rifles, very few do it at an elite level – and when they do, they often complain about not getting the desired results.

Few sports are as obsessed with minutiae as shooting. It’s not just with the scoring system, where they deal in decimals, but everything from the velocity of the bullet, which mustn’t be less than 250m/sec (in rapid fire pistol), to the thickness of the underwear, which shouldn’t be more than 2.5mm.

David Goodfellow, the chairman of ISSF’s rifle jury, has a phrase to describe the shooters: “nut behind the butt.”

The clothing

Rajmond Debevec belongs to an era when the targets were bigger and scores were lower. The Slovenian, 55, is the oldest competitor in Delhi. This is his 42nd year competing internationally and is the only shooter to have competed in all 34 World Cups. The rifle 3-position world record he set in 1992 stands even today and he is third on the list of most Olympic appearances (8) across sport.

He is the grand-daddy of world shooting; eyewitness to the sport’s evolution through the decades. “When I started competing internationally (in 1977), the equipment was worse. Hence, the scores were much lower,” Debevec says.

The rifles weren’t as sophisticated as they are today, targets were still manually operated and even though the size of the bullseye was relatively bigger, the scores were relatively low. “I won my first medal at the European Championship, a silver, with a score of 383 out of a possible 400. If I were to translate it to today’s pattern, I would need around 395-396 out of 400 to finish on podium,” he says.

The 13-point jump is almost equivalent to the average score in ODIs jumping from 250 to 350+ over the last decade. The advances in rifle technology, of course, have made a lot of previously-unimaginable things possible. But the biggest difference, Debevec says, is the clothing.

Shooters stand in awkward postures for hours – keep an apple as a target, stand facing it, align your hips to a 12 o’clock position and aim with an imaginary rifle. Now stand like that for a couple of hours, without moving. That’s what shooters do every day.

“The argument was that, with the rifle in particular, because shooting doesn’t create muscle men, you didn’t want to create strain and stress while holding a rifle owing to its weight,” Goodfellow says. “Because it’s a long match, hour and a quarter, and with the hours and hours of training they do every day, it can cause back problems. To try and prevent as a safety measure, for health of athletes, you allow clothing to give certain amount of stability but not support.”

The trousers were first to make an entry, in the mid 80s, and they revolutionised the sport. They restricted hip movement and when the jackets were introduced, they helped in cancelling out the vibrations due to increased heartbeats and recoil and breathing during tense moments in a match. Fewer movements during a shot resulted in better accuracy and, thus, the high scores.

Shiny kit syndrome

The bat has been a subject of one of cricket’s biggest debates, with many arguing that the blade, as thick as the face, has taken skills out of the game. Shooting grapples with similar problems in relation to the clothing.

“You don’t want to take it to ridiculous extremes, where somebody could be standing there in the armour and the only thing they actually move is their trigger finger while everything else is stationary. It takes the skill out,” Goodfellow says. “Some people call it technological doping because there are certain manufacturers who keep pushing the envelope for sales. If someone wearing their gear goes on to win an Olympic medal, it goes on to create – what we call in military terms – a shiny kit syndrome. Suddenly, you have others who think, ‘I’ve got to have one of those’.”

At the Seoul Olympics, when the jackets and trousers were first used, the checks were made manually. Goran Maksimovic, the 10m air rifle gold medalist at those Games, says they were asked to keep the jackets and trousers upright on a table and the clothing would pass the test only if it collapsed on the ground promptly, on its own. “However, since it was stiffer than usual clothing, it didn’t happen. So one day before our event, most of us were cutting our jackets with blades. After the Olympics, we had to buy new ones,” Maksimovic says.

The ISSF continued to experiment with various testing methods until a German firm introduced equipment that standardised the process. Subsequently, rules were laid down – a shooter can use just one jacket and trouser during a tournament; the thickness shouldn’t exceed 2.5mm while stiffness should be a minimum of 3mm.

In theory, shooters need to get their clothing tested just once. Once they receive a ‘yellow card’, a seal of approval from ISSF, they do not need to get it checked again, unless they change the clothing. But in practice, most shooters get their clothes cleared before the tournament to avoid the embarrassment of getting randomly picked for tests and failing it.

Last May, several shooters gave equipment control a miss at the Fort Benning World Cup in USA since most had passed the test at Changwon in South Korea the week before. Maksimovic says the jury called nearly a dozen shooters for tests after the event and almost all of them were disqualified after they failed the test. One of them was his daughter Ivanka, a London Olympics silver medallist. A couple of months later, at the Jakarta Asian Games, Indian rifle shooter Ravi Kumar had to virtually destroy his jacket — one he had been using since 2011 – to get past equipment control.

Ravi says his scores haven’t been the same since he started using the new jacket. “So I think I will repair the old one and start using it again,” he says.

Watch your weight

A rookie mistake, India coach Deepali Deshpande says, is weight change. Like every other equipment, clothing is custom made. Unlike jerseys in other sports – where an athlete can exchange with his teammates if something goes wrong – a shooting jacket is cut according to the shooter’s size. “If you don’t set your jacket properly, then it has a direct impact on your game. You have to maintain your weight because your clothing needs to fit in a perfect manner,” Deshpande says.

The ISSF has rules even about how loose or tight clothing can be, so even a tiniest of change in body structure is frowned upon. That is one of the reasons you hardly see drastic changes in a rifle shooter’s size. Debevec jokes he has been eating the same quantity of food for the last four decades and been doing same exercise to ensure he does not gain too much weight, or lose a lot.

A slight change and the shooter will be forced to buy a new jacket and go through the tedious equipment control process all over again. “Not maintaining your body can prove to be very costly,” Deshpande says. At least Rs 60,000, for that’s how much decent jacket and trousers cost.

The flat-bottom boots

Sergei Kaminskiy has a shoe fetish. But not for the ones he wears at the range. “It makes you walk like a zombie,” the Russian, a Rio Olympics silver medallist, says. The boots worn by shooters are flat-bottomed and have customised insoles, which gives them ankle stability and reduces front-and-back movement while aiming at the target. Like clothing, they too have to pass vigorous testing before an athlete can use them. The sole, for instance, must bend at least 22.5 degrees; the upper part should be made from soft, pliable material with maximum thickness of 4mm.

According to the ISSF rules, “to demonstrate that soles are flexible, athletes must walk normally (heel-toe) at all times while on the field of play. A warning will be given for the first offense, a two-point penalty and disqualification will be given for subsequent violations.”

A good quality shoe, Ravi says, can cost up to 220 euros (approx Rs 17,000). While the make is mostly similar, the difference is the manner in which shooters tie their laces. “It’s a mental thing. I pull my laces tight since I feel that improves my balance. Some shooters tie it loose. But if I do that, I am afraid I will fall,” he says.

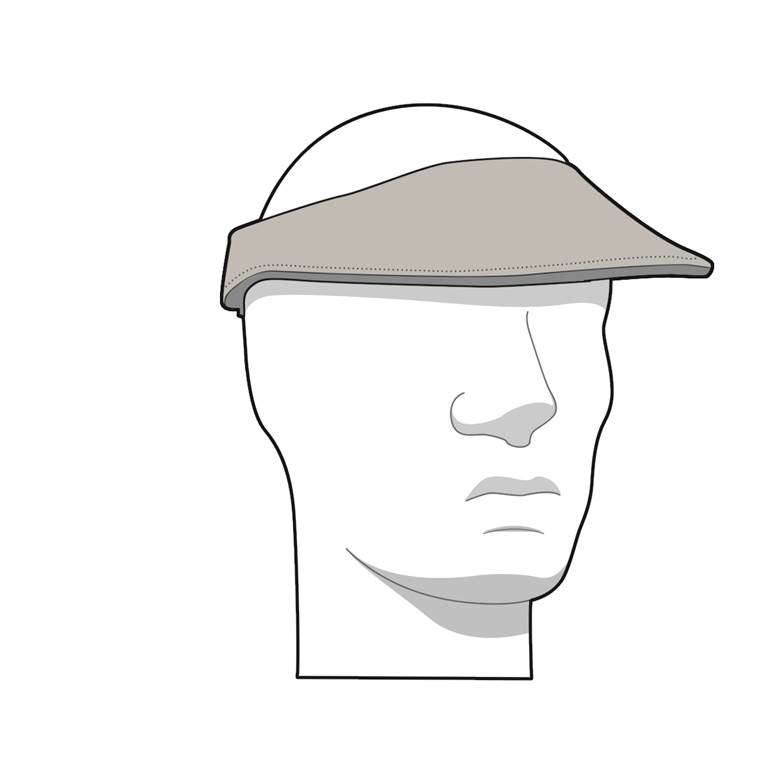

The visor

The disco lights irritate Germany’s Julia Simon Anita. But she, like others, has to get used to it. Shooting faces an uncertain future at the Olympics, whose marketing executives have suggested the sport doesn’t generate much television viewership. For the ISSF, there was a deeper problem – their events had no takers at all. So the ISSF’s new president, Russian billionaire Vladimir Lissin, decided to bear production costs and get the World Cups on TV networks.

To jazz up the coverage, disco lights have been installed in shooting halls. While it may enhance production quality, the flashiness made it difficult for the shooters to aim at the target. That’s where the visors come in handy. “It can get very difficult with the new lighting. But you do not have same light at every range, so visor is very important for me because it blocks the light and gives clear picture of the target,” Anita says. “In Munich, you have light above your head for the cameras. So you can’t see the bullseye unless you wear the visor.”

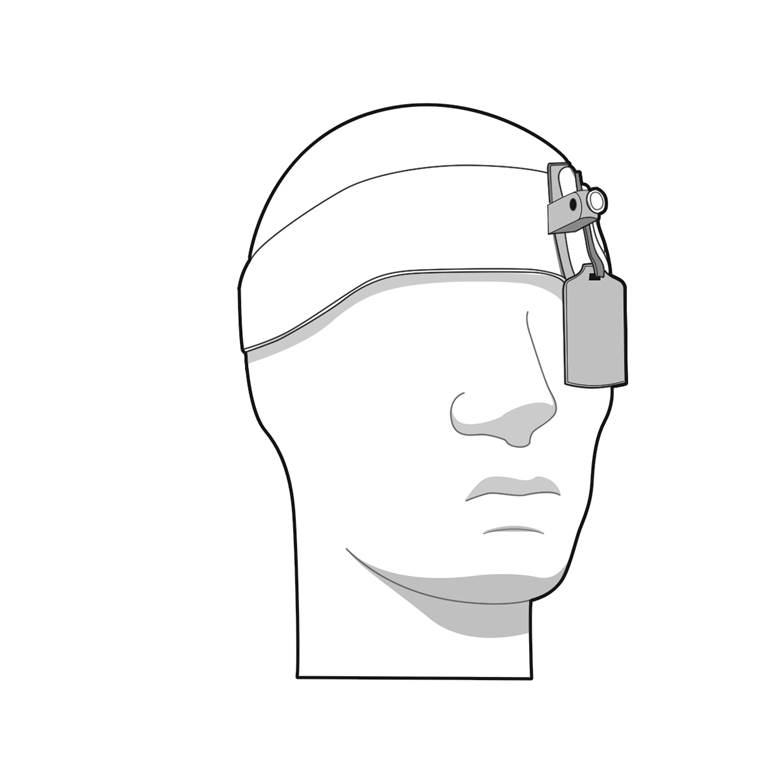

To avoid double picture when aiming, some shooters also use blinders. “But they can cause problems when it’s windy and you want to see flags on the sides which indicate the direction and speed,” Maksimovic says. “In that case, you follow some rules. The first flag is more important than others because it is just 10m away. With little movement of the eye, you look at the flag, see the direction of the wind, turn to the target, and shoot.”

Shooters gear

Jacket

Dimensions: Maximum thickness of 2.5mm and must hang loose — to determine that, the overlap must be at least 70mm, measured from centre button to outer edge of button hole.

Helps in cancelling out the vibrations due to increased heartbeats and breathing during tense moments in a match. Thickness and stiffness is measured to ensure the rifle does not completely rest on the jacket, thus giving the shooter an undue advantage.

Blinder

Dimensions: Not more than 30mm wide.

Worn to cover the non-aiming eye and helps in avoiding double picture when aiming. Shooters also use side-blinders, which can be attached to the hat, cap, shooting glasses or headband.

Trouser

Dimensions: 2.5mm thick; must be worn higher than 50mm above crest of hipbone

Restricts hip movement and hence improves stability while standing in an awkward position for hours. Pockets are not allowed but to support the trousers, a normal waist belt (maximum 40mm wide and 3mm thick) is permitted.

Boots

Dimensions: Must bend at least 22.5 degrees

Flat-bottomed and customised insole, helps in improving balance and ankle stability. To demonstrate that soles are flexible, athletes are advised to walk normally at all times while on the field of play. The flexibility is measured to ensure a shooter does not get unfair advantage. If the sole is too hard or the material used is too thick, the natural movement is restricted, giving the shooter extra stability.

Visor

Dimensions: Can extend forward of athlete’s forehead no more than 80mm.

Glove

Dimensions: Total thickness of 12mm maximum and must not extend more than 50mm beyond the wrist, measured from the center of the wrist knuckle.

Not a necessity, some use it for better, non-slip grip and support for the rifle.

Rifle

Dimensions: Total weight: 5.5kg max; length of barrel: 850mm; trigger weight: free for air rifle and 1,500 gram for standard rifle.

Every part is extremely crucial and personalised, but the shooters lay a lot of emphasis on getting top grade ammunition and factory-matched barrel for better results.