As a child, artist Manjunath Kamath was fascinated by fables, folktales and myth. He recollects building his own narratives from the characters that he was introduced to — be it the gods and goddesses in the mythological tales that his grandmother would narrate to him or the protagonists in the Yakshagana theatre performances that he would attend with his father. He would also spend hours observing sculptures in religious sites across Mangalore, including the Kadri Manjunatheshwara, after which he was named. “Those temples and churches were my first museums,” says the Delhi-based artist. While his friends would be out playing, young Kamath would be sketching at home or watching terracotta idol makers moulding Ganesha and Durga.

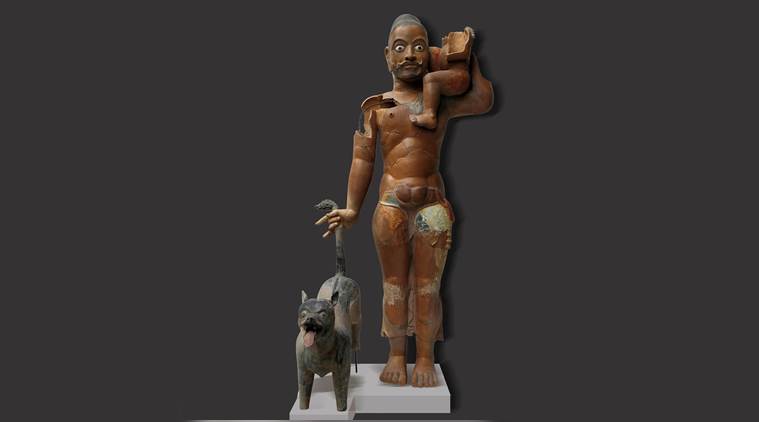

Those memories form the essence of his art that is rooted in tradition and literature and aspires to establish links between the classical and contemporary. “I work spontaneously, oscillating from one form to another. It’s like a puzzle that the viewers have to join,” says Kamath, 46. His exhibition titled ‘Era Elsewhere’ at Gallery Espace in Delhi envisions the showcase as if it belongs to a museum. While the wall works are replete with iconography from the miniature traditions, Kamath refers to ritual images and local deities to create his own terracotta sculptures. “Several villages have their own deities that might have no connection with Vedic deities. I found it interesting how recent attempts were made to establish connections between Brahmanism and local deities. In line with this, in this exhibition, I create a non-existing era where you get glimpses of different periods of history,” says the artist. So the 36 x 41 x 12 inches terracotta sculpture Ego Icon has a bull and a tiger, representing the Vaishnavite-Shaivite conflict and the constantly changing power structures. With its hollow head,Pokkadettaya is the “god of lies” who compels viewers to examine their own deceptions.

Known for the satire and wit with which he tackles socio-political issues, it took Kamath several years to develop his visual vocabulary. When the graduate from the Chamarajendra Academy of Visual Arts in Mysore first arrived in Delhi in the mid ’90s, he spent three-four months at the Bahawalpur House, where his co-residents included artist GR Iranna. He made a living designing t-shirts for People Tree and working as an illustrator with a newspaper, till he decided to dedicate more hours to his art. A recipient of the Charles Wallace scholarship in 1999, as a artist-in-residence at the University of Wales Institute in Cardiff, he visited several museums in the UK but the artefacts would often remind him of India. “Historical Indian paintings have contributed greatly to world art. It made me wonder what I was doing and should be doing,” he says.

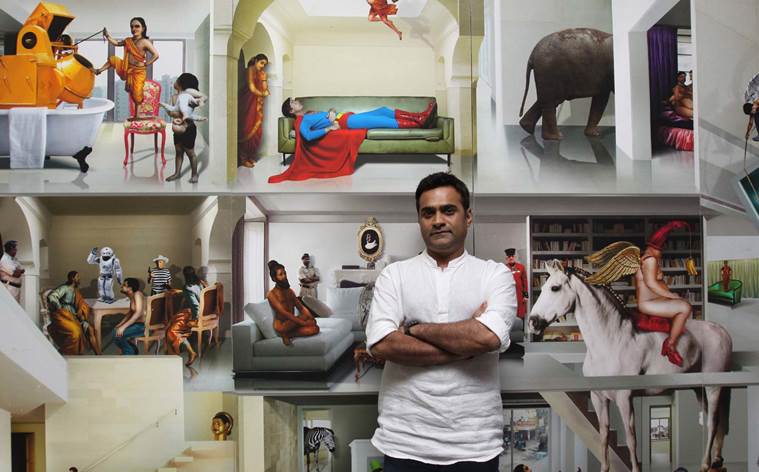

While his first solo in 1996 at Shridharani Gallery, Delhi, ‘About Something’ featured more abstract compositions, a decade later, when he presented his next solo ‘Something Happened’ in 2006, Kamath was working with videos, clay animation and digital prints, where the references ranged from Nathdwara paintings to German oleographs and superheroes met Raja Ravi Varma’s protagonists.

In his critically acclaimed debut in Mumbai at Sakshi Gallery in 2011 he attempted to “declutter” his compositions. Dedicated to the late artist Prabhakar Barwe, the exhibition saw Kamath move towards minimalism in his practice.

Conventions were also questioned when in 2010 for the project ‘Conscious-Subconscious’ he turned the walls at Gallery Espace into his canvas for a week, doodling and painting impromptu and interacting with the visitors. “A studio is usually a private space. Here, I turned a public space into a private one. It was challenging; I felt empty in the end,” says Kamath.

In the more recent works, he questions history and popular perceptions. He refers to Thomas McEvilley’s The Shape of Ancient Thought that examines how Western philosophies were influenced by Greek and Indian thought. “History is fictional and manipulated. It is based on interpretations and each one fills the gaps according to their inclinations and perceptions,” says Kamath, who lets the viewers build their own stories around his protagonists.