In Prabhakar Barwe’s Red Envelope, a deceptively simple work from 1995, one can sense the presence of the artist himself, hovering at the edge of the painting. Perhaps, as we look down at this still-life — an assortment of pencils, paintbrushes, a pair of spectacles and the titular bright red envelope — we’re in the position of the artist as he looks down at his workspace. Maybe, he just wrote a letter and sealed it in the envelope. The longer one looks at this work, the more questions crowd one’s mind, especially since it was in 1995 – the year in which he painted Red Envelope — that Barwe took ill and passed away. He was only 58. Could the red envelope then mean something more? Is it possible that the artist knew his demise was imminent and the unseen letter inside the envelope hints at that?

These may seem like fanciful questions in the case of most artists, but not Barwe, whose works always hint at a horizon beyond which lie things that only he could see. The most mundane objects — boxes, leaves, safety pins, pencils and fruit — when painted by him acquire monumental proportions, holding a significance that their real-life versions couldn’t possibly hold, and the expanses of space in his works vibrate with a presence not made immediately obvious on the canvas. “He created his own language, and his own symbolism,” says Jesal Thacker, founder of Bodhana Arts and Research Foundation, and curator of ‘Inside the Empty Box’, a Barwe retrospective that opened at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) in Mumbai on February 8. “It’s not so easy to classify Barwe. Modern Indian art is classified into narrative, figurative and abstract, and you can’t put him in any one category,” says Thacker.

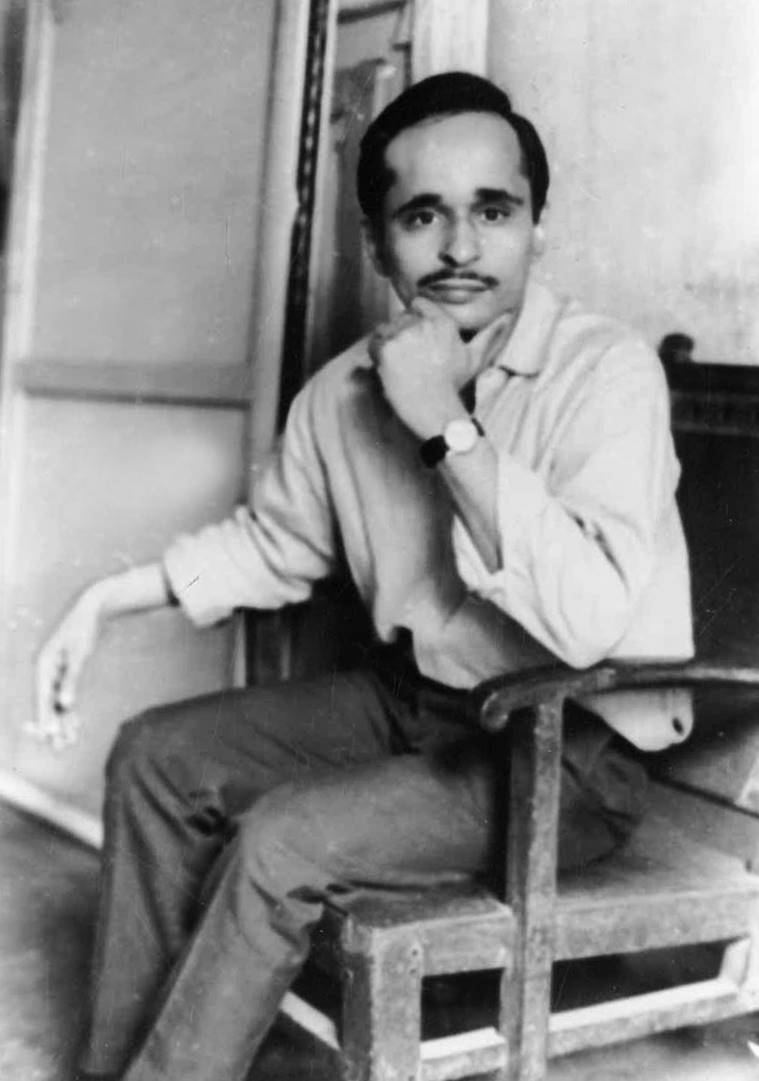

Born in 1936 in Nagaon, Maharashtra, Barwe grew up with his grandparents in the village. He moved to Mumbai (then Bombay) soon after Independence, to live with his parents, Shivram and Shanta, in a chawl in Lalbaug. Art was in Barwe’s blood — his father made a living as a sculptor, working in film studios, while his uncle was the sculptor Vinayak Pandurang Karmarkar, well-known for his statues of Shivaji Maharaj. Karmarkar, in fact, was instrumental in Barwe’s decision to go to the Sir JJ School of Arts in 1954. The young artist flourished in the intellectual atmosphere at the art school and immersed in literature and the ideas of painters such as Paul Klee, Barwe, who had already begun to chafe against the rigidly academic style espoused by his uncle, turned towards abstraction.

The intellectual explorations that one sees in Barwe’s works began when he was still a student at the JJ School of Arts, and they found a greater impetus when he joined the Weavers’ Service Centre in 1961, less than two years after graduating from art school. The Centre, initiated by Pupul Jayakar, invited leading contemporary artists to collaborate with traditional weavers, thus creating a cross-disciplinary atmosphere similar to that which Barwe had found in art school. This period of his career was especially important, because his first posting was in Benaras where he picked up Tantric philosophy, which would shape his artistic expression in the years to come. Upon his return to Mumbai in 1965, he continued working with the Weavers’ Service Centre, using his evenings to refine his approach into the distinct spare style that he is now best known for. Over the years, he kept evolving this style, even incorporating ordinary objects such as matchboxes and playing cards that had always fascinated him, into his canvases and imbuing them with a meaning beyond the obvious.

Barwe wrote prolifically, analysing his own works and sketching out ideas in journals. Many of his musings on art and creation can be found in Kora Canvas, the book he published in 1980. All this material put together — along with the works on display at NGMA — present a clear portrait of Barwe the artist. It is harder, however, to get an understanding of Barwe the man. He rarely wrote about himself, and even in conversations, only his closest friends would be trusted with personal observations. His sole preoccupation, recalls artist Dilip Ranade, 68, was his art. “Even when hospitalised, he would talk for hours about art. No matter who visited his studio, whether it was a plumber or an electrician, he would seek their opinion on his work,” says Ranade. He describes Barwe as an easy, engaging personality with a sense of humour that could dissipate the tension in any gathering, but also someone who was intensely private.

Though never a “celebrity” unlike his more flamboyant contemporaries like MF Husain, Barwe was highly respected by other artists and critics. His works won awards, including the Lalit Kala Akademi award in 1976 for Blue Cloud, an ode to Kalidasa’s Meghadutam, and they have been placed in prestigious collections around the world. When he died in 1995, the vacuum he left in Indian contemporary art was deeply felt.

“The one thing that you will see every time is that he saw art in everything, even in safety pins and boxes. To him, a box was not just a box, even when it was empty. It was the beginning of a whole host of questions, all of which he sought to answer through his work,” says Thacker.