Recipes For Change

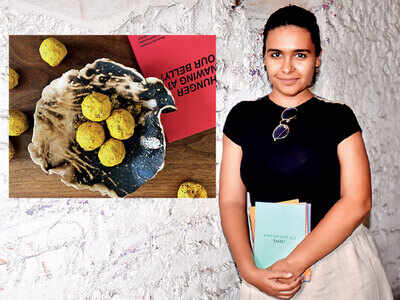

(Left) Rajyashri Goody’s work titled Manu Laddoos featuring laddoos made out of Manusmriti pulp and a ceramic bhaakar or bhakri, a flatbread cooked in Maharashtra using sorghum or rice flour

The beef ban in India was at its lowest point in India in 2016. Vigilante cow protection groups were in full force, indiscriminately lynching or attacking those who were suspected of being in possession of beef, a meat that has been a staple for Christians, Muslims and Dalits in the country. The ban also prohibited cow slaughter for leather trade.

A Dalit family of leather workers in Una was publicly flogged by gau rakshaks for having skinned a dead cow. Artist Rajyashri Goody, then 25, was in Korea on an art residency that year. Born to a British father and Dalit mother, Goody was only a year into her art practice then, but had always been compelled to write about Dalit history. “The Una protests had just happened. Because Brahmins are vegetarian, and are the most powerful caste who have had the most access to literacy and writing, India is seen as a vegetarian country. Brahmins are not even a majority here. Since I was in a foreign country, I was able to see that even something as basic as food was governed by a power narrative so I started thinking about these stereotypes,” recalls Goody.

Goody also began to notice a pattern in the Dalit literature that she had read. “All the Dalit memoirs I’ve read have so much writing about food. Almost every chapter has so much about food. It shows you that link between discrimination, caste, hunger and experiences of eating. The strongest and deepest traumas of childhood are to do with hunger and not having enough to eat,” says Goody. With a Masters degree in Visual Anthropology from the University of Manchester, Goody felt that food offered her a powerful tool to study caste history.

Social worker and Marathi novelist Laxman Gaikwad’s book, Uchalya (The Branded), was the first piece of Dalit literature that Goody picked up to begin her recipe book project. Her recipes read like a poem, written like a set of instructions for a regular recipe, but are in fact, disturbing food memories from Dalit autobiographies. “It took me six months to develop the first book. The recipes are not consumerist, but a complex way of talking about caste struggle and the suffering.

People still don’t understand that Dalit cuisine is not a cuisine. Dalits have a complicated relationship with food because of the lack of it and the shame associated with it,” says Goody.

Here’s a sample from the translated version of Uchalya Make a fire. Roast the rats. Carry the remains home For mother.

The Uchalya community that Gaikwad belongs to was known as the thieving tribe. “His book was super graphic. His community had a hard time because they were traditionally thieves and the police had their names recorded,” says Goody. If anything untoward, particularly a robbery, had happened in the village or town that the Uchalya community lived, the members of the community would be brought into the police station for questioning or worse the police would barge into their homes and thrash their families until they admitted to the crime that they may or may not have committed. “After a point, they (Uchalya) were stealing to get by and as a way of resistance. They weren’t allowed to own land, so stealing was the only way they could get food. Their ingenious ways of letting rats loose in fields to steal wheat was one of the things Gaikwad wrote about. The way he spoke about approaching things like food and hunger was painful, but also had this pride to it,” says Goody, whose recipes were also showcased as part of an exhibition at Harvard University. Part of the exhibition was an installation that included laddoos made from the material that was created after pulping Manusmriti, the Hindu text that justifies caste system. The laddoos were placed on a bhakri made out of ceramic. The image is striking in that it immediately provides context and a contrast in the caste structures in India, again via food. “As an artist, these recipes are not just about trauma either. It’s got humour, which is very important in art,” adds Goody.

Marathi writer Urmila Pawar’s Aaydan: The Weave of My Life, Indian-American author Sujata Gidla’s Ants Among Elephants, Tamil feminist Bama’s Karukku and poet Omprakash Valmiki’s Joothan are among the books that have inspired Goody to write recipes. “Urmila Pawar’s book spoke about women collecting oysters from the beach and how treacherous these journeys were. They had to trek up and down a hill during the low tide to collect oysters. Women would get dragged into the ocean or slip down a hill and die.

The writer describes it to be a feat,” says Goody. Her art would not exist if not for these memoirs, admits Goody. “These experiences have been so well written and well put together in the memoirs. I don’t imagine a scenario — it’s already there. I just change the language in the extract from first person to second,” she says.

There is “no grand agenda of gaining a huge following for her art” through her recipes, explains Goody. “Dalit literature is still not that popular, so I thought I’d put it out in the form of recipes.

It’s a sort of fetishisation that I am playing with. If the recipes brought about even a tiny shift in how the reader perceives food cultures and food politics, that would be the ideal effect. But more importantly, I’d like the recipes to intrigue the reader to go out and buy the book I’ve collected the recipes from, and read more Dalit literature,” says the artist, who grew up in Pune and studied sociology atFergusson College .

Dalit activist Baby Kamble’s book The Prisons We Broke and We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement by Meenakshi Moon and Urmila Pawar are the latest additions to Goody’s reading list. “I started by reading whatever my parents had at home, which was quite an extensive collection, but now I’m making an active effort to seek out more female Dalit writers, as well as autobiographies from across India, and not just focused onMaharashtra ,” she says.

Goody’s work will be part of Shifting Studios, a group presentation by city-based artists, at TIFA Working Studios today.

A Dalit family of leather workers in Una was publicly flogged by gau rakshaks for having skinned a dead cow. Artist Rajyashri Goody, then 25, was in Korea on an art residency that year. Born to a British father and Dalit mother, Goody was only a year into her art practice then, but had always been compelled to write about Dalit history. “The Una protests had just happened. Because Brahmins are vegetarian, and are the most powerful caste who have had the most access to literacy and writing, India is seen as a vegetarian country. Brahmins are not even a majority here. Since I was in a foreign country, I was able to see that even something as basic as food was governed by a power narrative so I started thinking about these stereotypes,” recalls Goody.

Goody also began to notice a pattern in the Dalit literature that she had read. “All the Dalit memoirs I’ve read have so much writing about food. Almost every chapter has so much about food. It shows you that link between discrimination, caste, hunger and experiences of eating. The strongest and deepest traumas of childhood are to do with hunger and not having enough to eat,” says Goody. With a Masters degree in Visual Anthropology from the University of Manchester, Goody felt that food offered her a powerful tool to study caste history.

“Up until this point I wasn’t sure whether I was just making huge statements about caste and social structure, but I wanted to find my own interest within that, which made it special for me. For me, this was about understanding my own Dalit history,” she adds.

Social worker and Marathi novelist Laxman Gaikwad’s book, Uchalya (The Branded), was the first piece of Dalit literature that Goody picked up to begin her recipe book project. Her recipes read like a poem, written like a set of instructions for a regular recipe, but are in fact, disturbing food memories from Dalit autobiographies. “It took me six months to develop the first book. The recipes are not consumerist, but a complex way of talking about caste struggle and the suffering.

People still don’t understand that Dalit cuisine is not a cuisine. Dalits have a complicated relationship with food because of the lack of it and the shame associated with it,” says Goody.

Here’s a sample from the translated version of Uchalya Make a fire. Roast the rats. Carry the remains home For mother.

The Uchalya community that Gaikwad belongs to was known as the thieving tribe. “His book was super graphic. His community had a hard time because they were traditionally thieves and the police had their names recorded,” says Goody. If anything untoward, particularly a robbery, had happened in the village or town that the Uchalya community lived, the members of the community would be brought into the police station for questioning or worse the police would barge into their homes and thrash their families until they admitted to the crime that they may or may not have committed. “After a point, they (Uchalya) were stealing to get by and as a way of resistance. They weren’t allowed to own land, so stealing was the only way they could get food. Their ingenious ways of letting rats loose in fields to steal wheat was one of the things Gaikwad wrote about. The way he spoke about approaching things like food and hunger was painful, but also had this pride to it,” says Goody, whose recipes were also showcased as part of an exhibition at Harvard University. Part of the exhibition was an installation that included laddoos made from the material that was created after pulping Manusmriti, the Hindu text that justifies caste system. The laddoos were placed on a bhakri made out of ceramic. The image is striking in that it immediately provides context and a contrast in the caste structures in India, again via food. “As an artist, these recipes are not just about trauma either. It’s got humour, which is very important in art,” adds Goody.

Marathi writer Urmila Pawar’s Aaydan: The Weave of My Life, Indian-American author Sujata Gidla’s Ants Among Elephants, Tamil feminist Bama’s Karukku and poet Omprakash Valmiki’s Joothan are among the books that have inspired Goody to write recipes. “Urmila Pawar’s book spoke about women collecting oysters from the beach and how treacherous these journeys were. They had to trek up and down a hill during the low tide to collect oysters. Women would get dragged into the ocean or slip down a hill and die.

The writer describes it to be a feat,” says Goody. Her art would not exist if not for these memoirs, admits Goody. “These experiences have been so well written and well put together in the memoirs. I don’t imagine a scenario — it’s already there. I just change the language in the extract from first person to second,” she says.

There is “no grand agenda of gaining a huge following for her art” through her recipes, explains Goody. “Dalit literature is still not that popular, so I thought I’d put it out in the form of recipes.

It’s a sort of fetishisation that I am playing with. If the recipes brought about even a tiny shift in how the reader perceives food cultures and food politics, that would be the ideal effect. But more importantly, I’d like the recipes to intrigue the reader to go out and buy the book I’ve collected the recipes from, and read more Dalit literature,” says the artist, who grew up in Pune and studied sociology at

Dalit activist Baby Kamble’s book The Prisons We Broke and We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement by Meenakshi Moon and Urmila Pawar are the latest additions to Goody’s reading list. “I started by reading whatever my parents had at home, which was quite an extensive collection, but now I’m making an active effort to seek out more female Dalit writers, as well as autobiographies from across India, and not just focused on

Goody’s work will be part of Shifting Studios, a group presentation by city-based artists, at TIFA Working Studios today.

FROM AROUND THE WEB

GALLERIES View more photos

Recent Messages ()

Please rate before posting your Review

SIGN IN WITH

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.