Kharar, Mohali

Written by Manraj Grewal

Farman Safvi doesn’t remember the exact year he became a hero of sorts in these parts. “It was around the time I came here, about eight years ago,” says the 25-year-old, sitting at a cafe in Kharar, a township and educational hub on the fringes of Mohali. That year, he claims, he “rescued a local girl who was being harassed by a drunkard”.

In the years since then, says the Kashmiri from Budgam, he has become a bit of a Punjabi himself. He likes his butter-chicken “dhaba style”, speaks “reasonably good” Punjabi and has taken to local politics. Some years ago, Safvi, with some of his friends, even helped found the Kashmir Students’ Union in Panjab University, Chandigarh. ‘’I also canvassed for Kang sahib (the Congress candidate from Kharar) in the Punjab Assembly polls,’’ he beams.

“I have a lot of friends among the locals… People joke that I have even started looking Punjabi,’’ adds the BTech graduate from Doaba Group of Colleges in Kharar.

Kharar, with the dust from the under-construction flyover hanging like a permanent haze, is as far as it gets from the snow-capped mountains and the chinar trees of Kashmir. Yet, for the thousands of students from J&K who study in its institutions and live on campuses and in rented homes outside, drawn by scholarships and the hope of a “normal life”, Kharar is, as most of them call it, “a second home”. An estimated 6,000 Kashmiri students now study and live in Kharar and nearby areas such as Landran and Gharuan that are part of Mohali district.

In the days after the attack on a CRPF convoy in Pulwama, faced by mobs in Dehradun and elsewhere, many Kashmiri students fled to Kharar and its nearby tehsils, such as the shelter home in Landran and Gurudwara Shaheedan Sohana in Mohali.

Last Sunday, members of the gurudwara’s managing committee contacted the students at their shelter home — a few apartments in Landran — and threw open their doors to them.

Amanpreet Singh, the regional coordinator of Khalsa Aid, a global not-for-profit organisation founded by Ravi Singh in London in 1999, says that so far, they have evacuated 310 students from Kharar and nearby areas to Jammu.

“The students were quite fearful and wanted to reach home but many of them didn’t have enough money. Prices of air tickets had shot up and there were no buses to Jammu due to the curfew there. So we brought them here,’’ Singh says, adding that they later hired eight mini-buses and sent over a hundred of these students back home on the night of February 18 under Punjab Police escort. Singh says that most of the students are now back in Kashmir, and only a few left at the shelter home.

Though far from the mobs, Kashmiri students in Kharar admit that over the past few days, they sometimes felt the chill.

Inside a two-bedroom apartment in Kharar, as a group of students sit chatting, Pulwama and the events that followed dominate their conversation. ‘’Kharar is peaceful. But you can feel the tension in the air. On campuses, there have been instances of people turning around and lecturing Kashmiris, as if it is all our fault. What is our fault?’’ asks Naveed Iqbal, a second-year student of civil engineering at Chandigarh Group of Colleges, Jhanjheri, who shares the flat with Aafaq Ahmad, a student of BCA.

‘’Our parents are very worried, they call us a dozen times a day,’’ says Irfan Sarwar, a second-year student of B.Pharm at Shahid Udham Singh College of Engineering and Technology, Tangori, who returned from his hostel nearby to stay with his friends in Kharar after two Kashmiri students in his college were suspended for an ‘offensive’ post. “It’s unfair to target us. Does anyone in the Valley take their anger out on people from other states who are working there?’’

Yet, Mudassir Rather, a 22-year-old from Hardushiva village of Sopore, would rather stay on in Kharar. Having graduated in civil engineering from Kharar’s Guru Gobind Singh College of Modern Technology in June last year, Rather has applied for an MTech seat.

“I like it here… this place opened my mind, changed my thought process, made me think beyond the binary of Kashmiris and non-Kashmiris. I have made some very dear friends in the last four years,’’ he says, adding that he heard about Kharar from his Kashmiri seniors. “I simply followed them here. There are limited educational opportunities in Kashmir. Chandigarh is the closest big city we have. So for many of us, Punjab is the first option after Class 12,” he adds.

The private Chandigarh University near Gharuan in Mohali has 1,937 students from J&K on its rolls. Chairman Satnam Singh Sandhu says the number has been growing steadily. ‘’We started with 150 students from J&K in 2012; look at how far we have come,’’ he says.

These numbers are driven primarily by scholarships offered both by the Central and J&K government. The Prime Minister’s Special Scholarship Scheme (PMSSS) offers 5,000 scholarships every year to students of J&K domicile after their Class 12. Under the scheme, around 8,780 Kashmiri students are studying in institutions across the country, 1,601 of them in Punjab.

As colleges seek to draw students and build their reputation, some of the newer ones in the region even offer rebates to students from Kashmir. Jagdeep Sinh, director of the Institute of Engineering and Technology in Bhaddal near Kharar, says they offer students discounts ranging from 15 per cent to 40 per cent.

‘’It’s not charity. We need good students and they need affordable education,’’ says Singh.

Gurvinder Bahra, director of Rayat and Bahra University, says Kharar’s biggest draw among Kashmiri students is its proximity to Chandigarh and connectivity to J&K. ‘’A youngster needs a life beyond academics and Kharar fits that bill,” he says.

With its malls and food joints, its army of autos and app-based cabs, local vendors who speak a smattering of Kashmiri, the popular Tamanna salons and the highway dhabas that offer halal meat, Kharar has played the perfect host to the Kashmiri students.

Rather recalls being dazzled the first time he stepped into an MNC food store in Kharar. ‘’I was a village kid then and these joints seemed so plush, like they were from another world.’’ It was in Kharar that Rather watched a movie in a hall for the first time in his life —PK, he smiles. He has since graduated to watching Punjabi movies — “Yaar Anmulle is my all-time favourite. We often bond with the locals over Punjabi songs. We Kashmiris have even contributed to making Punjabi songs a rage in the Valley. We may or may not understand the lyrics but we can sing along,’’ he says.

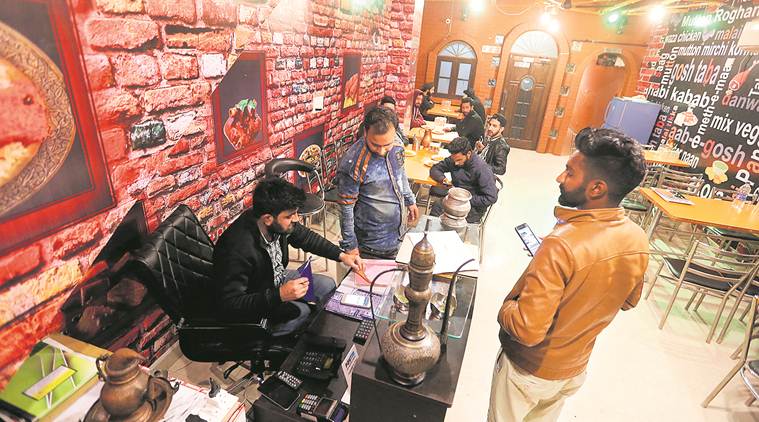

And when they miss “home food”, they simply head to Mughal Darbar restaurant for some “authentic” wazwan. Its owner, Tawseef Rashid, a Kashmiri who came to Kharar as a student and stayed on, now runs two branches of the restaurant in the town.

Back at the apartment, the conversation has moved beyond Pulwama to Kharar and how it’s closest to “home”. “Yahan aake sukoon milta hai (I get a sense of peace here),’’ says Aafaq Ahmad, who has been here a year and a half.

Which is why, says Rather, it’s important for Kashmiri students to stay on, despite a gnawing fear that creeps in sometimes. ‘’Students link us to one another, they hold a promise of peace, we cannot break this thread,’’ he says.

Pune

‘This city is mature not to confuse our pens for guns’

Written by Anjali Marar

When his father came visiting Javed Wani — a year after the 10-year-old had left his home in Budgam, Kashmir, and joined a school in Pune — he remembers telling the senior Wani: “I haven’t seen a single gun (in Pune) in the last one year.”

Now a first-year B.Ed student in Poona College, Wani, 24, says that back home in his village, the violence and uncertainty meant he barely attended school two or three times a week. That’s when an uncle suggested that the boy be sent to Pune.

It was a rough start — the nine-year-old could only speak Kashmiri and didn’t know why he was being sent here, away from his parents and friends in the village. The food, the culture, the city boys —all seemed new and alien, but he clung on.

Home now is Pune, a city he “is in love with”. On Kashmiri students being targeted following the Pulwama attack, Wani says, “Unlike other cities, Pune is mature to not confuse the pens of students for guns.”

Pune’s colleges and education hubs host students from across the country, with hundreds of them from J&K enrolled in courses ranging from commerce to business administration, medicine and nursing. Of 1,056 Kashmiri students studying in Maharashtra under the Prime Minister’s Special Scholarship Scheme, a substantial number are estimated to be from Pune.

Javed wishes some of his classmates in his village school had got the opportunities he did. “Most of my 20 classmates are today either carpenters or drivers in Budgam or nearby places. I am the only student from my class who studied till MA, and it would not have happened had I not come out of my village,” he says.

Owais Wani, 24, an aspiring model and a student of business administration in Savitribai Phule Pune University (SSPU), says he is grateful to his two elder sisters, whom he followed from Budgam to Pune.

“There is no scope for modelling back home. While here, I can travel to Mumbai or Bengaluru for assignments,” says Owais.

After completing a course in Pune more than a decade ago, his eldest sister runs her own architecture firm in the city while his middle sister is doing her PhD in economics from SSPU.

As tension over Pulwama simmers across the country, the Kashmiri students here say it’s important for better sense and peace to prevail. “Whenever I go home, I interact with young students and tell them to explore the country. After hearing our stories, there are many who want to study in bigger cities outside the state. Attacks on Kashmiri students will only deter them,” says Javed.

Dehradun

Week after threats forced many to leave, fear in air

Written by Kavita Upadhyay

A week after right-wing groups created a ruckus at colleges in Dehradun, demanding that Kashmiri students be ousted, a hostile chill hangs in the air, exacerbated only by the intermittent rain. Police personnel stand guard across the city — a van with eight policemen stands outside Baba Farid Institute of Technology, where protests by right-wing groups on February 15 had forced the principal to state that no Kashmiri student would be admitted in the new academic session.

At Sudhowala, a locality in Dehradun that’s a student hub, with flats on rents, paying-guest accommodation and dhabas catering to them, it’s business as usual — almost. Sudhowala’s Kashmiri students have all left for their homes in Kashmir. An estimated 3,000 Kashmiri students study in various higher education institutions across Dehradun, many on scholarships, others drawn by the city’s laidback, peaceful atmosphere. “Until this incident, we never faced any discrimination. Everything was so good, but now it’s all over,” says a 22-year-old from Bandipora in Kashmir, who is in her third year of journalism at the Dehradun-based Sai Group of Institutions.

On February 17, five Kashmiri youth walked in a tight group in a locality near the Dehradun bus terminus, their eyes to the ground. “We are going to meet our (Kashmiri) friends… we have to ensure they are safe. We must get out of Dehradun as soon as possible,” said a 25-year-old from Kashmir’s Sopore, who is in his final year of a medical laboratory course at the Uttaranchal (PG) College. As he spoke, his phone buzzed continuously – “It’s my father… he has been worried,” he said after a hurried exchange in Kashmiri.

The group entered a room on the first floor of a two-storey house, which had been rented by their friends. Inside, on two mattresses on the floor, stood at least nine Kashmiri students, including four girls, talking on their phones to relatives back home. About 10 others stood in the verandah.

A 23-year-old from Kupwara said, “When I reached Dehradun six years ago, I felt my world transform. The notions I had about the rest of the country changed. We didn’t experience any prejudice. People were good to us.”

But the Pulwama attack changed everything. “Is it fair to treat us this way when all we wanted was to educate ourselves and build a career?” he said.

A week later, all the 19 students in the house that day had left the city.