In his 2012 poem To The Hyphenated Poets, Amit Majmudar writes, “Richer than mother’s milk/is half-and-half./ Friends of two minds, redouble your craft./…Being two beings requires/ a rage for rigour,/ rewritable memory,/ hybrid vigour.” Early in his life, in negotiating this tricky terrain of identity, the Ohio-based writer, translator and radiologist of Indian origin would stumble upon an elixir — religion. And not just of the land his immigrant parents had left behind, but also of that part of the world he had known as home. Hinduism and Christianity would bridge the dichotomy of his life with the sort of “hybrid vigour” he had been in search of.

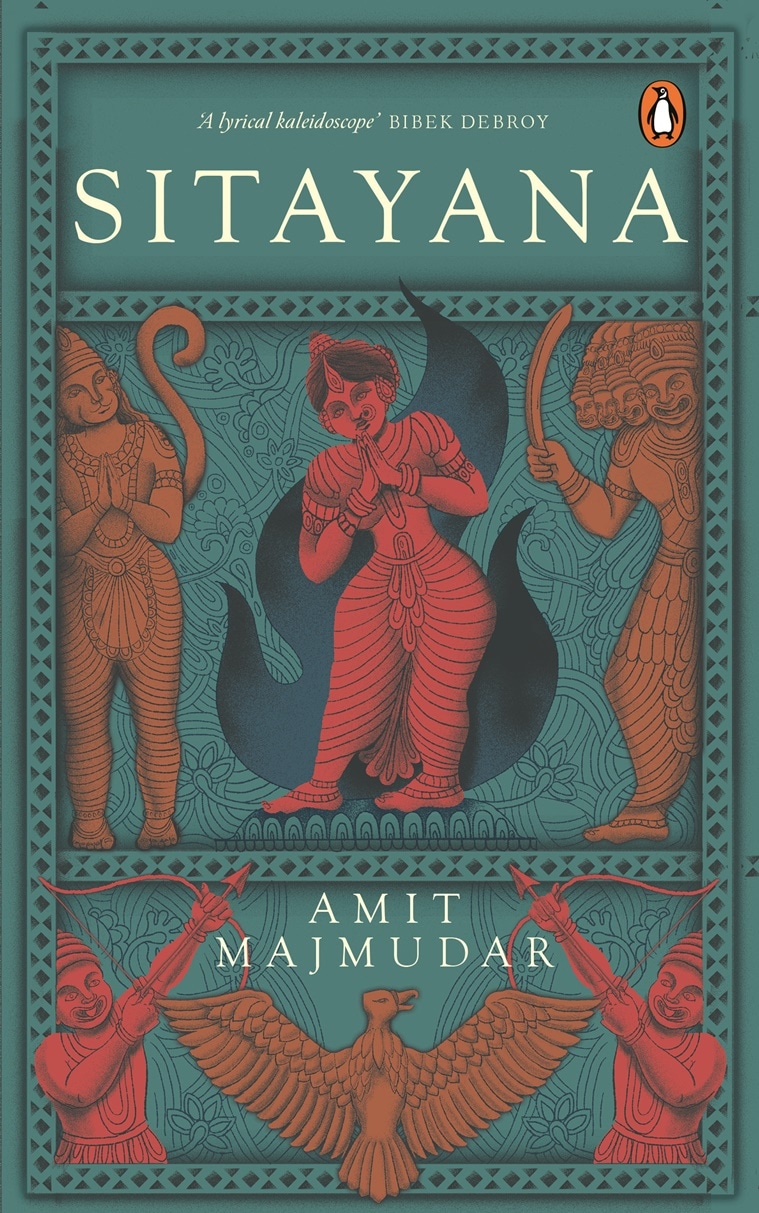

“I became interested in religion very early, and not just Hinduism. I read the Upanishads in translation on my own when I was about 12 years old. I was drawn to it, intensely and inexplicably, and I believe in my heart that there was some momentum from a past life driving me toward such studies,” says Majmudar, 40, whose latest book, Sitayana (Penguin Random House, Rs 399), is the story of Ramayana, told by an ensemble cast of characters led by Sita.

In his essay, “Three Hundred Ramayanas” (1987), AK Ramanujan wrote, “I have come to prefer the word ‘tellings’ to the usual terms ‘versions’ or ‘variants’ because the latter terms can and typically do imply that there is an invariant, an original or Ur-text — usually Valmiki’s Sanskrit Ramayana, the earliest and most prestigious of them all.”

In Majmudar’s rich and lyrical rendition, the Ramayana becomes an empathetic record of gender inequality and Sita’s unique resistance to it, of the chasm between what is ideal and that which is real. But most of all, it is a reminder of the centrality of Karma in human lives, a theme he explored in its complexity in his breakout work, Godsong: A Verse Translation of the Bhagavad-Gita With Commentary (2018).

The telling of an epic from the perspective of different members of its vast pool of characters is a well-worn trope — Indian-American writer Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni foregrounds Sita’s perspective in her new novel, The Forest of Enchantments (2019), as did Samhita Arni in Sita’s Ramayana (2011), and the 15th century Bengali poet Chandravati long before them; Ravana is the hero in Dravidar Kazhagam architect Periyar’s version of the epic, to name just a handful of examples. But this very act of reconstruction is also a political one. Majmudar, however, is unwilling to call his writing reactionary.

“In America, some religious groups are politicised or agitate politically — evangelical Christians, anti-abortion Catholics, Muslims, pro-Israel Jews, and so forth. But American Hindus are too small a demographic to be pandered to, and too well-assimilated and successful to be very interested in political agitation. So when I write on Hindu subjects, like Sitayana and Godsong, it is utterly free of political import for me as an American,” he insists.

Born into a family of doctors — his parents and sister all practise medicine — the sciences and the arts have run concurrent courses in his life. A critically-acclaimed poet, Majmudar, who has also written two novels, delves into themes of selfhood, spirituality and the clash of civilisations in collections such as the 2011 Donald Justice prize-winning volume, Heaven and Earth, Dothead (2016) and 0°,0° (Zero Degrees, Zero Degrees). For someone so keenly interested in ideas of the self, Ohio’s first Poet Laureate (2015-2017) is not indifferent to the intolerance debate playing out in different parts of the world nor to the role religion plays in it.

“Indian intellectuals focus on religious intolerance within India, but the nuclearised Indo-Pak divide is the real legacy of mass democratic politics and religious identitarianism. The religious divide was intentionally and strategically inflamed in the run-up to the Partition, to make sure Pakistan came into existence; and millions live under nuclear threat as a result, all these decades later. Such exploitable divides, racial in America or religious in India, will never vanish; it is idealistic to imagine that. They will only get more or less inflamed. Like racial divisions in America, religious divisions in India will remain a chronic ailment, like arthritis. Care must be taken by all responsible people not to inflame the joint — to manage, as it were, what will never be completely cured,” he says.

As a practising radiologist, Majmudar says some of the tools of his trade coincide with his writerly life.

“A radiologist has to be precise and careful with his words, as does a poet or novelist,” he says.

This self-awareness goes a long way to puncture the rupture that modern life often imposes between science and faith.

“I maintain a sense of the limitations of science. I don’t try and make it answer questions it’s not designed to answer. It (science) is the study of maya, of the illusory material reality, of the laws, patterns and processes of the physical world. I do not seek truths from science regarding things that don’t have to do with atoms and cells. Science is good for what it’s good for. I have the Gita for everything else,” says Majmudar.

This article appeared in print with the headline ‘The Handbook of Life Skills’