Lounging on a sofa at his Mumbai home, with the 99 names of Allah inscribed in a panel above him, the only decorative piece on the living-room wall, Wasim Jaffer, fresh from being part of Vidarbha’s second Ranji Trophy-winning campaign, talks about his life and cricket. In the wooden television cabinet opposite him, there are a few of his trophies, but even there his five-year old son’s two awards for winning a school race occupy the pride of place.

There are no photographs of him or his family. He says it’s not just because of his religion’s mandate, but also because “it feels arrogant to have your own picture in your home”. We might as well have got up, switched off the recorder, and walked out of the house then — for those two quotes above say everything that needs to be said about Jaffer the man. But the sweets he had offered, the ones bought from Nagpur after his incredible 10th Ranji Trophy title victory, were too tempting to let go. So, we stay.

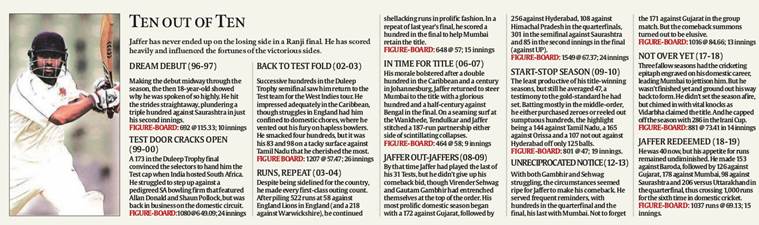

If there is someone who can be called India’s ‘Mr Cricket’, it has to be Jaffer. Ten victorious Ranji finals; the highest scorer in the history of the Ranji, the Duleep and the Irani Trophies — and, at one point, even of the limited-overs Vijay Hazare tournament. Add to it the countless runs he has scored in England’s league cricket, where he has been going for 20 years now — just when you think he might let satisfaction slip into any hint of hubris, he offers this: “First of all, I think I was lucky to have played for Mumbai. With Mumbai, you are bound to win a lot of Ranji titles. Almighty has been kind to me.”

Sensing that this chat is going nowhere, you drag his wife Ayesha to talk up her husband. She laughs to say, “Ego? Forget that, he hardly shows anger even. He is a man at peace with himself — in fact, I would say after the Indian dreams faded away, he is pretty happy playing cricket for whatever team he plays for. And all I now want is for him to stay at home for longer. Get a day job, please!”

One of the reasons he has continued to play for so many years (he turns 41 next week) is the fear of what would happen to him if he quits. He is an employee of Indian Oil and he dreads the day he would have to start a “9 to 5” work schedule. Just the thought of it stirs dread in Jaffer.

“All my life, I have known only cricket. I would like to be involved with the game — be it coaching (he has successfully mentored young players in Vidarbha in the last two years), or commentating. That’s what I am thinking now.”

Is the cricketing end near?

“Well, I think so. If Chandrakant Pandit (his friend and the coach of Vidarbha) stays there next year and they want me, then fine. I like that team environment. If he goes somewhere else, maybe I can go there but all that depends. It does look like I won’t play for long. Let’s see. I feel blessed that I have got so much, achieved all this, when you consider the kind of environment from where I came. I have seen many players more talented than I was who haven’t had the cricketing life I have had. God has been kind.”

***

It’s to his childhood that we rewind now to understand the man. At a chawl in the bowels of Bandra, amidst what used to be a transit camp, there lived a bus driver in a small shanty. A fan of fast bowler Ramakant Desai and the Pakistani opening batsmen Hanif Mohammad, he would be glued to cricket on the radio. He had just one wish — that at least one of his four sons would play cricket for India. One son, Kalim, had the talent but the family didn’t have the means to support him.

“Father was the only one earning and my elder brother was a talented player. But the family couldn’t afford it. You had to buy bat, or shoes, or have money to travel for competitions and soon, time ran out for him. It was then that they decided that I would play cricket for India.”

Kalim became Jaffer’s coach, teaching him the basics and taking him to Mumbai’s maidaans.

The family started to do odd jobs to make more money; they also started a pickle business. “We would make 6-7 types of pickles, one brother would take it in his rickshaw to sell it and whatever they earned would go into the family pot. My mother started other odd jobs as well — like making clothes, anything and everything that could get us some extra money.” As a young boy, Jaffer too would give a helping hand in the pickle-making process.

His childhood was a blur of cricketing dreams and fears. A 10-year-old boy who was told he should play for India. A 12-year-old who realised he had to be successful in cricket if he wanted to pull his family out of financial distress. A 15-year-old who dreaded coming home if he hadn’t scored runs, not because he was scared of his family, but because his batting was the barometer of the family’s mood. “They would get sad, if I hadn’t scored runs. When I did, all of them would be happy.”

He would take the 6.15 am train to his school in town, Anjuman Islam near Victoria Terminus (VT). Play cricket from 7 to 9 am before attending school and back to the game from 2 to 6 pm. “It was the beginning of my serious cricket pursuit. At Anjuman, all I thought and did was to play cricket.” Especially after his seventh grade, where he was third-ranked across all the six sections. “I was pretty good in studies but my family felt that I should put all my energies in cricket. And it was something I loved doing. I had to struggle for everything in life. Nothing came easy but I stuck on.”

He would not initially get selected for the Mumbai Under-16 team, a setback that made Jaffer cry. “My family told me that I need to score lot more runs. Otherwise I won’t make it.” One step forward, one step back. By the sheer weight of runs, at 18, he was playing the Ranji Trophy.

Such was the pressure, such was the talent in Mumbai then that the teenager thought if he didn’t score in his second game after he had failed in the first, his career would end.

“There were so many talented kids around.” In his second first-class game, he responded by scoring an unbeaten triple ton — and that eased his Ranji worries. Soon came the India call-up.

***

The happiest memory attached to his India debut in 2000 was the fact that he could afford to send his parents on the Haj pilgrimage. “They weren’t there to see my debut but, more importantly, they were at Haj. It was such a happy occasion. My father, a mild-mannered, simple, and extremely hard-working man, had just one dream and I had got there. My mother was a woman with a strong character who didn’t worry too much about my cricket, but to have made both of them proud and happy by playing for India – it’s something that I’m most proud of to this day.”

His mother passed away in 2003, but his father watched his final stint with the Test team, from March 2006 to April 2008. “He obviously wished that I had done more, but I knew he was happy that I had done what I could.”

His international cricket journey is well known — the double century in the West Indies, the special hundred in Cape Town, South Africa, and the runs in England, every time there was a worry about his inconsistency, he would bounce back with a torrent of runs in domestic cricket. But it was the 2008 series in Australia that, he reckons, eventually ended his India career.

“I had problems with Brett Lee’s bowling I would admit, I didn’t know how to cope, but the primary feeling, as I recall now, was that I would be very disturbed around then. Disturbed because I was not doing well in that series and I had put so much pressure on myself — that I have to do well.”

With him in those sombre Australian evenings was his wife, and the two got over the disappointment soon.

“It was not as if I was broken or something. I never showed much, never vented out or did anything like that,” he says. His wife nods in agreement.

“Looking back, I feel that I wasn’t in the best mental space then. But my natural temperament doesn’t allow me to be down for long. I work hard for things but don’t let it affect me if it doesn’t go the way I want it. As I said before, it’s God’s wish. You deserve what you get. You can’t be bitter,” Jaffer adds.

***

One of the best things that happened to him when he was playing for India was meeting his wife in 2002. For this, he has Rahul Dravid to thank. Ayesha, born and brought up in England, went to the team hotel during a series in England to catch her favourite player, Dravid, and met Jaffer in the process. “I have told Rahul that it was because of him we met up!” Jaffer says.

It’s such a charming love story that also reveals the personality of the man, according to Ayesha. And hers too, for that matter.

“When he would come to play in the England league in Yorkshire, he would come to London to see me. We would spend hours sitting in parks. Hyde Park, Marble Arch… and just talk. What I liked about him was his simplicity. He had no airs. And his commitment stood out for me,” she says.

It’s a relationship that Jaffer thinks would not happen in this day and age.

“We would meet once in 6 months, that’s all. Rest was through MSN Messenger. Once a week, she would call me using a phone card. She would get a pin number from my friend, dial a number, give that pin, and connect to me. Rest were all through chats. Six months of separation — I don’t think it can happen these days.”

Very early in the relationship, Jaffer told her that he would marry her. “I went whoa!” laughs Ayesha. A gentle smile creases Jaffer’s face. Beside him sits his son, and by her side is their daughter, wearing earphones and immersed in an iPad. “We were like friends for the first two years before we got really serious,” says Ayesha.

She gushes about Jaffer’s commitment that made her wilt and decide to move out of a comfortable life in London. She left her parents and all her friends behind to come and live in Mumbai with Jaffer after their marriage in 2006. “It wasn’t easy,” says Jaffer. “But she made it all seem easy. My mother was not there by then, and I have no sisters. She had to do everything alone.”

The first two years wasn’t a problem at all, says Ayesha. The kids weren’t born yet and she would travel the world with Jaffer. “I remember the fun times we had. The wives of other cricketers — of Rahul, Tendulkar, Kumble — were all so friendly. I remember I would want to do something, Wasim won’t be sure about it but I would ask Vijeta (Dravid’s wife), ‘Can I do that? Can I go there?’ And she would say ‘yes yes do that, go there’, or whatever I had wanted to do.”

Those are some of the good days the couple cherish. Like this one time in Rome when he was playing for India and they had to take the local train. “He was sure that no one would recognise him, but I told him he would be and if they did, he would have do to whatever I say the whole day. And as soon as we got in, he was recognised.” What did he have to do that day? “Nothing. Mainey maaf kar diya!” “No, I remember I got her a perfume!” says Jaffer.

Travelling by the local train is something that Jaffer does even now in Mumbai. A visit to the Bandra cricket ground from his home in Juhu-Versova link road, or to Mira road. “People do recognise me, I smile, and go.”

At times, he can be seen emerging from certain shanty colonies in Mumbai’s suburbs. “Some of my friends live there.” His most funny recollection of fans came in a lift in a hotel during a Haj pilgrimage. “I was without chappals and was standing there when two Gujaratis got in and started to talk: ‘This looks like Jaffer.’ The other said why would he be here and like this?! I just kept quiet, and they walked away.”

The most hype around him was perhaps in 2014, when he was playing league cricket in England. They would give overseas professionals a car apart from accommodation and that year the car sponsor decided to spray paint: ‘This car is driven by Wasim Jaffer’. “Everyone knew wherever I went,” he sounds embarrassed. To think the reserved Jaffer driving through the streets with his name sprawled across is quite an image.

On second thoughts, perhaps, the marketing men in England got the stature of Jaffer better than us in India. He might be a quiet, content, peaceful man, modest to a fault about his cricketing achievements, but in the years to come, it would be something to say that we have seen India’s Mr Cricket bat. And bat. And so gracefully at that. The final word on his story goes to him then:

“I feel blessed. I haven’t heard a single bad thing about me. Even now when people meet, they don’t say, chances diya tha lekin fail ho gaya (he failed for India). Instead they appreciate my style of batting and say, they wish I had played for India more. People respect me. And you can’t buy that. What more can I ask?”