If there’s one proof of the Narendra Modi government’s trade policy undergoing a distinct shift over the last nearly two years in response to agrarian unrest – from pro-consumer to pro-farmer — it is the numbers relating to farm imports.

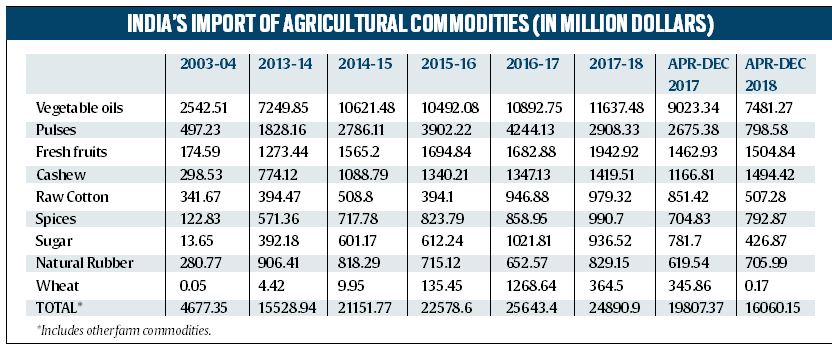

Between 2013-14 (the last year of the previous Congress-led UPA dispensation) and 2016-17, the value of India’s agricultural commodity imports soared from $15.53 billion to $25.64 billion. But in 2017-18, this fell to $24.89 billion, while registering an even sharper 18.9% year-on-year decline during the first three quarters of the current fiscal (see table).

The best indicator of the Modi government’s trade policy shift is pulses.

In 2013-14, the country imported 36.55 lakh tonnes (LT) of pulses that was worth $1.83 billion. By 2016-17, these had shot up to 66.09 LT and $4.24 billion, respectively. However, in 2017-18, imports dipped in both quantity (56.08 lt) and value ($2.91 billion) terms. During April-December 2018, just over 10 LT of pulses valued at $798.58 million got imported. This came even as the Modi government, in August 2017, moved imports of tur/arhar (pigeon-pea), urad (black gram) and moong (green gram) from the “free” to the “restricted” list. The same quantitative restrictions – not allowing imports beyond a certain annual (fiscal year) limit — were extended to yellow/white peas in April 2018. Also, a steep 60% import duty was clamped on chana (chickpea) with effect from March 2018.

In edible oils, too, imports surged from $7.25 billion in 2013-14 to $10.89 billion in 2016-17 and $11.64 billion in 2017-18. However, following increases in customs duties — which came into effect first on March 1, 2018 for crude and refined palm oils (from 30% to 44% and from 40% to 54%, respectively) and, then, on June 14, 2018 for crude soyabean oil (from 30% to 35%) and crude sunflower and rapeseed oil (from 25% to 35%) — edible oil imports have also recorded a 17.1% drop during April-December 2018 over April-December 2017.

Likewise, import of sugar and wheat saw a spike between 2013-14 and 2016-17. This, along with the country importing a record quantity of pulses amid a bumper domestic crop in 2016-17, was a reflection of the Modi government’s general hawkishness with regard to food inflation during this period. That stance has somewhat eased since, especially with growing farmer anger over collapse in produce prices post the November 2016 demonetisation. Not only have farm imports slowed down after 2017-18, the Modi government has also abandoned the conservative policy vis-à-vis minimum support price (MSP) hikes that marked the first three years of its rule.

The first three years of the Modi government notably witnessed both a jump in agricultural imports as well as a slide in exports — making it a double whammy for farmers. The latter plunged from $ 43.25 billion in 2013-14 to $ 33.70 billion in 2016-17, reversing the boom in shipments that took place during the preceding ten years under the UPA rule. Exports recovered a tad to $ 38.90 billion in 2017-18, only to marginally fall in this fiscal. Either way, they are yet to go back to their peak achieved in the last year of the UPA regime.

Much of the troubles faced by farmers during the Modi government’s period can be attributed to the crash in global prices of agri-commodities, which have, on the one hand, made it difficult to export and, on the other, also increased the vulnerability to imports. This has been further compounded by the adoption of aggressive inflation-targeting (the implications of it obvious, when food items have a 45.86% weight in the consumer price index) and a strong rupee (its real effective exchange rate, against a basket of 36 currencies and adjusted for inflation differentials, appreciated by 15.9% between 2013-14 and 2017-18). Only in the last one year or more has there been some amount of exchange rate correction along with conscious efforts at boosting farm prices, whether through higher MSPs, raising import tariffs or removing restrictions on exports.

An idea of what the boom (and subsequent bust) in exports entailed can be had from individual commodities.

Take cotton, the exports of which shot up from a mere $205.08 million in 2003-04 to $ 4.33 billion in 2011-12. The huge overseas demand for the fibre enabled farmers in Saurashtra to get over Rs 1,300 for every 20 kg of kapas (raw un-ginned cotton) and Modi, who was then Gujarat chief minister, to demand a rate of Rs 1,500. But with exports averaging hardly $ 1.9 billion in the last four years – because of the global benchmark Cotlook ‘A’ cotton price plummeting from 244 cents a pound in March 2001 to current 82 cents levels – farmers today manage to get just Rs 1,070-1,080 per 20 kg.

Even better an example is guar-gum, whose shipments skyrocketed from $ 110.53 million to $ 3.92 billion. The impetus here came from the US shale oil boom: The said gum – extracted from the seeds of guar, a hardy legume crop grown mostly in Rajasthan – is used as a thickening agent in the fracking fluid (primarily water and suspended sands) that gets injected at high pressure into shale rocks to create cracks and allow the oil/gas to flow through them. As hydrocarbon drilling services firms such as Halliburton, Baker Hughes and Schlumberger began stockpiling guar-gum, Indian exporters and farmers, too, made a killing. On March 21, 2012, spot prices of guar-seed in Jodhpur hit an all-time-high of Rs 30,432 per quintal. That rate now is around Rs 4,200 – which is explained purely by annual exports barely at $ 650 billion.

Another instructive case is of maize. In 2000-01, India shipped out 32,500 tonnes of this feed grain valued at $5.97 million. By 2012-13, these had reached 4.79 million tonnes (MT) and $1.31 billion, respectively, as big multinational traders started sourcing maize from Bihar’s Kosi-Seemanchal belt and even Nabarangpur in Odisha for dispatching to southeast Asian markets via Kakinada and Visakhapatnam ports.

There are many other such commodities from soyabean and basmati to buffalo meat and skimmed milk powder, where high prices for farmers were clearly driven by exports. As that boom ended, so did the fortunes of Indian farmers suffer. And, of course, aggravated by policies more pro-consumer than pro-producer.