Museum: A ‘way of seeing’ that evolved through the ages

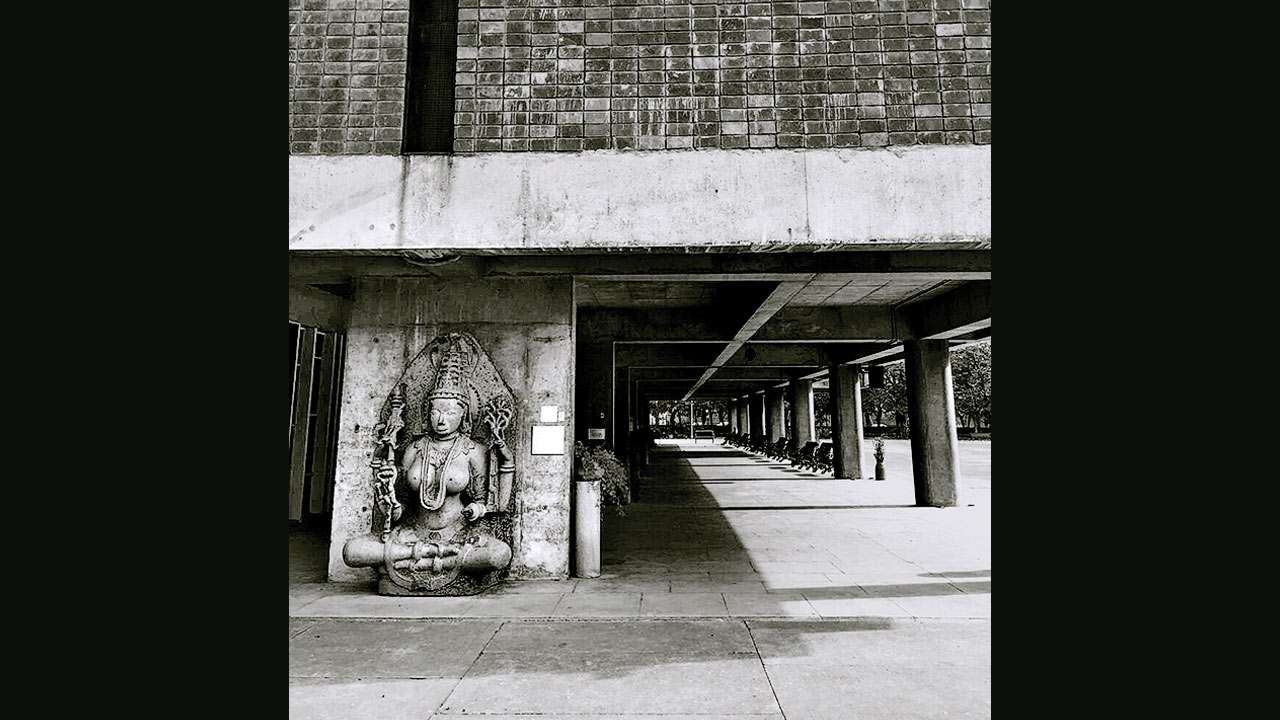

Chandigarh Museum and Art Gallery Chandigarh Museum and Art Gallery - Sakoon Singh

“For many Europeans, India was a vast museum, its countryside filled with ruins, its people representing past ages... a source of collectibles and curiosities, to fill European museums, botanical gardens and zoos and country houses.” — Bernard S Cohn, Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge.

Taking off from where John Berger left, a museum is, at the end of the day, a way of seeing. While Berger inhabited relatively innocent times, it would be useful to conflate the museum space with post-colonial sensibility.

Essentially an arrangement of materiality, it additionally directs the gaze in a peculiar way. When they were first set up, museums reinforced the encyclopaedic obsession of 19th century, that involved enumeration, classification, cataloguing — of objects, flora, fauna, samples of all kinds (including human) and in the process, charging the objects with a kind of hyper signification. In crossing over from “cabinets of curiosity” of the Renaissance times to museum, marked a change in the enterprise: From collecting to ordering to examining in exultation. It was not enough to collect “booty” anymore, it was also important to order it in a certain way.

Bernard Cohn thinks of a museum as a peculiar “form of knowing” that proliferated with colonialism. He terms is as the museumological modality. Marked with an imperial gaze, it connotes a triumph of exploitation, exultation of possession, characterised by superlative ordering and refined empiricism, devised such as to be gazed at with awe and wonderment. The ritual of a museum visit entails a solemnity and sobriety, a certain seriousness in the purpose of “witnessing”. Berger highlights how the experience of witnessing the “internal silence” of a painting is exaggerated with the museum’s strategically controlled lighting. Extraneous elements are thereby added to the largely visual experience of seeing a painting.

Human exhibits in times of slavery, where prospective buyers could “check out” racial peculiarities was another form of museum-ificaton. Sometimes, part of a circus entourage, these drew huge crowds. At other times these were exhibited in imperial nations as samples of subdued humanity, especially when nationalism was thunderously ascending as a sentiment. The Great Crystal Exhibition (1851), designed by Joseph Paxton, was a culmination of many such amateur and professional efforts. An amalgam of high design, diligence and curated objects, it stood in the heart of London as a flamboyant plate glass and cast iron symbol of Empire. James Fergusson, who came to India as an indigo planter and extensively travelled the country from 1837-42, curated the Indian component of the Crystal exhibition. Kew Gardens, likewise, a staggering ensemble of plant specimens from around the world represented not just English might in Botany but also its naval and strategic prowess. These spectacles, like Queen’s jubilee celebrations were part of the national pageantry, mediated attempts towards glorification of power.

The mood about conquest was sanguine, “to follow knowledge like a sinking star” and “it’s never too late to seek a newer world”, and in this Tennysonian optimism, knowledge and land/wealth appeared as one: “Yet all experience is an arch wherethro’/ Gleams that untravell’d world whose margins fades/ Forever and forever when I move.”

From the perspective of Indians, seeing their own materiality in the enclosed context of a museum space was curious. The very first museum in India set up in 1814 in Bengal was under the aegis of Asiatic Society. The Madras museum curator Thurston noted in his journal about the hoards that descended in the precincts on a government holiday were essentially family revellers picnicking and in their merriment, breaking all the rules of the sombre ritual of a museum visit. He, on his part was a phrenologist and is said to have been always ready with his calipers to study head structures of ‘natives’. Could it be a case of Indians reviling the museum as mock grand: Kim and street urchins playfully hanging upside down the Zam Zamahs installed in an imperial stance outside the Lahore Ajaib Ghar is case in point.

The idea of a museum is evolving, there are installations, museums of memory, museums of material memorabilia. There are the Biennales and Festivals, that fuse performance and exhibits and installations. Human exhibits are here again (Marina Abramovic and Ulay, “The Artist is Present” at MOMA, 2010), but nothing like what they were back in the day. A conventional museum space still presupposes a level of seriousness and familiarity with a tacit code of conduct. Sometimes it affords a quiet corner in the unkind metropolis for Indian lovers, claiming public places in the face of stark lack of private space. Many a lover is seen absorbed in an alternate performance right in front of a sombre medieval tapestry or a Pahari miniature.

Author teaches English literature