The upper echelons of pre-World War I Calcutta adored the Victorian culture. India’s capital had been shifted to Delhi, but the Raj remained close to its old flame as well. The Calcutta South Club was a byproduct of that affair. The Raj wanted something Wimbledon-like on the east of Suez. They found it on a few bighas of green along the Woodburn Road in 1920.

As snow covered the lawns in England, tennis migrated to warmer climes. Calcutta, the gateway to the East then, had several mercantile firms, filled with British employees and employers. They loved playing tennis, and South Club was the missing piece in the puzzle. To be fair, South Club was where the Occidental embraced the Oriental smile. Three Bengali gentlemen — founder members Akshoy Dey, Anandi Mookerjee and GC Dey — took care of the administration, building the club brick by brick, while SJ Matthews concentrated on unearthing talent through his coaching programme.

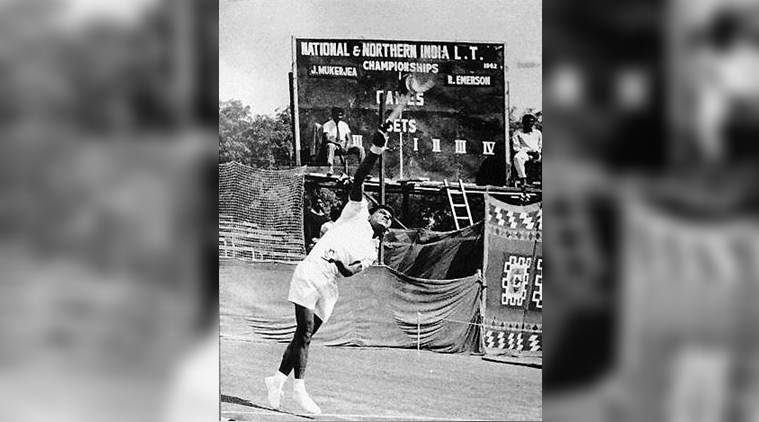

Inevitably, the great English pastime rubbed off on locals. The likes of Dilip Bose and Sumant Misra took up the sport and soon shone bright. Thus when the first Grass Court National Championship was held in India in 1946, South Club became its host by default. From Bose and Misra to Syed Fazaluddin via Naresh Kumar, Akhtar Ali, Jaidip Mukerjea, Premjit Lall, Zeeshan Ali and Leander Paes, this club has produced 12 Davis Cuppers and as many national champions. The venue also became a prime destination for the Davis Cup, hosting 11 ties. So this week, when the event returned to the home of Indian tennis after a gap of 16 years with the India-Italy tie, the old-timers made a nostalgic recollection, while the dilettantes felt the gravity of the occasion.

***

“Dimaag kharab ho gaya kya tumhara (Are you out of your mind)?,” the Indian Davis Cup Team non-playing captain Shamsher Singh snapped at team coach Akhtar Ali. There was that small matter of qualifying for the ‘Challenge Round’ (the title round in those days when Davis Cup winners didn’t have to line up for the early rounds the following year) and with the (also-defunct) Inter-Zonal final against Brazil tied at 1-1 after the first day, Ali had proposed a change in the doubles pairing, replacing Premjit Lall with Jaidip Mukerjea.

Ramanathan Krishnan had comfortably won the first singles but Mukerjea lost. Worse, Mukerjea played below par. Tension was palpable on that December 1966 evening at the Club. The Brazilians boasted of a younger, fitter two-man squad in Thomas Koch and Jose-Edison Mandarino who had pulled off an upset against heavyweights US in the previous round. The hosts were confident of a Krishnan double in the reverse singles. It was the second day’s doubles rubber that was the bone of contention.

“Jaidip had the big match temperament. And I preempted that the Brazilians would use the lob against us. Jaidip also had a very good overhead. The problem was that he had to play on the right court, forcing Krishnan to change his natural position,” Ali recounts, talking to The Indian Express. “I spoke to Krishnan and told him he was too good a player to make the adjustment. He agreed, but Shamsher Singh wasn’t convinced. Then Krishnan intervened and we had a new doubles pairing.”

It turned out to be an inspired decision as the scratch pair won the rubber, but the five-setter took a lot out of Mukerjea, who lost in another five sets to Mandarino in the first reverse singles. With the tie at 2-2, Krishnan took court against Koch. The latter had been leading 2-1 and 5-3 in the fourth set against Krishnan, when bad light provided reprieve.

“Next day on 15-30, Krishnan came up with a glorious backhand. The tie changed on its head from there. Koch choked,” the 79-year-old Ali reminisces.

The ever-so-professional All India Radio announcer tried to hold back her emotions as she announced: “India has entered the Davis Cup Challenge Round for the first time.” The hosts left the club having scripted history, and as Krishnan reached the team hotel, a panwallah bumped into him, bowed down and touched the player’s feet.

Mukerjea takes the story forward. India met Australia in the final in their backyard, rank underdogs against the might of Fred Stolle, Roy Emerson, John Newcombe and Tony Roche. Ahead of the doubles, Harry Hopman, the legendary non-playing captain of Australia advised Newcombe and Roche to use the lob to good effect.

“The pair hadn’t lost a match that season. But we, me and Krishnan, read their lobs well and defeated them. Back then, we used to have a 10-minute break after the third set,” says Mukerjea. “As we were heading to the locker room, Newcombe stopped and asked Hopman, ‘are we playing in Melbourne or the South Club in Calcutta?’ Many Indian fans had turned up for that tie, and they magnified the noise level.”

***

The 1930-31 British cricket tour of India had been cancelled citing ‘civil disturbances’ (the civil disobedience movement, more precisely), but Calcutta South Club still sent out a hopeful invitation to the International Lawn Tennis Club. The group, formed in 1923 to build camaraderie among nations through friendlies, was given the go-ahead to tour India. Future tennis correspondent Arthur Wallis Myers captained the visitors and later wrote: “Our faith in the symbolism of the International Club flag was justified.”

Henri Cochet’s France were the first foreign team to touch base at Calcutta South Club’s behest in 1929, and were greeted by pristine courts and a full house. Soon thereafter, South Club was playing host to players such as Yugoslavians J Pallada and F Puncec, Italy’s G de Steffani, Bunny Austin from Britain. Riding the momentum, Independent India organised its first international tournament in 1949 — the Asian Championship — and Dilip Bose won the title in Calcutta which made him a seed at the 1950 Wimbledon singles, an Indian first.

A flamboyant personality responsible for making South Club a favourite haunt among 1930s tennis’ backpackers was ‘Big Bill’ TIlden. The American, who won 10 Grand Slams and four professional majors during his 18-year amateur period of 1912–29, was a big draw at the venue. And Tilden reciprocated the love.

“The centre court at the South Club in Calcutta is one of the best grass courts, of my experience,” wrote Tilden in his 1938 memoir Aces, Places and Faults. Maalis (groundsmen) gave the South Club grasscourts a Wimbledon-like feel. During its earlier years, Kanu maali tended the lawns, ensuring not a single blade of grass was out of place. According to former Davis Cup captain Naresh Kumar, the diligence made Kanu, and fellow groundsmen, popular figures in the Indian tennis circles.

In 2006, the Cricket Club of India hired a South Club maali for a Davis Cup tie against Pakistan in Mumbai. “But they weren’t giving them anything. So I intervened and told them if they didn’t give him something around `20,000-25,000, I would make it a big issue. The payment was made next day,” Kumar breaks into a smile.

Of course, when the doyen of Indian tennis speaks, you listen. Kumar, who first played at the Wimbledon in 1949 and represented the country in 17 Davis Cup ties, believes that along with the grass courts, the sappy Calcutta weather also played a part in breaking down Europeans.

“I remember the match against then world No. 5 Sven Davidson at the 1956 Asian Championships. He was a tall, fit player but the scorching sun sapped the strength out of him,” Kumar told The Indian Express. “He lost in four sets.”

***

Younger brother Vijay’s breakout year of 1973 meant Anand Amritraj was now country’s second-best player. And when captain Ramanathan Krishnan handed debutant Jasjit Singh the second singles duty for the 1974 Eastern final against defending champions Australia, Anand was famously left feeling like a third wheel.

Defeats to Australia in 1972 and 1973 were one-sided, but they were also in Madras and Bangalore. Those assembled at the South Club, and on the neighbouring rooftops, believed. Jasjit too vindicated his captain’s faith with a marathon 11-9, 9-11, 12-10, 8-6 win over Bob Giltinan.

Enrico Piperno, former India Davis Cup coach, was a 14-year-old ballboy for the tie. “I remember Jasjit came to the locker room after the third set during that 10-minute break. Vijay Amritraj asked him, ‘Jasjit, how you feeling’? ‘I’m running on empty’, was his reply. He still had to play a set. Jasjit Singh refused to budge,” Piperno remembers.

Vijay’s loss in the second singles meant the onus was on him and Anand to give India the doubles advantage. The brothers got stuck in against John Alexander and Colin Dibley, and prevailed 17-15, 6-8, 6-3, 16-18, 6-4. Jasjit lost the reverse singles before Vijay saw off Giltinan to complete a famous win. The 327 games played under the hot May sun make it the longest Davis Cup tie ever.

Vijay and Anand put India in the final with a win over Soviet Union, but the Indian government boycotted the title clash against South Africa due to the South African government’s policy of apartheid.

***

The third Maharani consort of Jaipur, Gayatri Devi, fell for three sporting institutions in Calcutta – Mohun Bagan, Eden Gardens and South Club; her Bengali roots perhaps playing a part. In the mid-1950s, she turned up to play mixed doubles at South Club. “She sponsored me for three years. Without her help I would have struggled to make a career in tennis,” Akhtar Ali acknowledges.

In turn, Akhtar, brother Anwar, and fellow Clubmates helped shape India’s biggest tennis star. Eight-year-old Leander Paes used to come to the South Club on a bicycle with his domestic help. At La Martiniere for Boys, young Leander’s first love was football. Father and former hockey Olympian Dr Vece Paes decided a switch to tennis, after Leander suffered convulsion at the age of nine.

“The Ali brothers were his first coaches at South Club,” says Dr Paes. “One day, Premjit Lall called me and said, ‘this boy has got talent. Every Thursday bring him at 3.30pm and I will play with him for an hour’. Leander was very excited to have access to such renowned Davis Cup players.”

While brimming with athleticism, Paes’ style was unorthodox. The purists wrote him off, but Jaidip Mukerjea’s father Adip intervened.

“(Adip) used to be there, watching the youngsters play. ‘Don’t change his (Leander’s) style. His inconsistency is his strength’, that was the advice from Mukerjea Sr. And that has stayed with Leander right through his career. You don’t know what he is going to do,” Paes Sr says.

Leander sought entry to the Britannia Amritraj Tennis (BAT) Academy in Chennai. In the late 1980s, India were playing a Davis Cup tie against Sweden at South Club. “I approached Akhtar Ali. Akhtar in turn spoke to the Amritraj brothers. Ramesh Krishnan joined the conversation and said, ‘watch out, this guy is going to outwit you. After that Leander got a call up to join the BAT programme,” Dr Paes adds.

After being a ballboy at the 1985 win over Italy in Calcutta (when a prickly Claudio Panetta asked the line judge if the tennis was a little too fast for him), Leander commemorated his first outing as a Davis Cupper at the South Club with a straight-set win over a top-10 player Jakob Hlasek in the 1993 tie against Switzerland. He went on to become the tournament’s most successful doubles player with a record of 43-13, and amassed eight doubles and ten mixed doubles Grand Slams.

The 45-year-old however couldn’t make it to Davis Cup’s return to his backyard this week. “Sure, Calcutta, grass… not too bad on grass, am I? It’d be fun to play if I’m called,” Leander had said during the ATP World Tour event in Pune last year. “I think it’s important that the best team is chosen and I wish the team good luck. The results show for themselves and at the end of the day, there’s no secret about what’s going on in Davis Cup.”

***

Mahesh Bhupathi was born three weeks after that 1974 win against Australia, and played his first Davis Cup tie at the South Club against Hong Kong in 1995. The 44-year-old was back at the venue as India’s non-playing captain against Italy.

“We are just happy to be playing a big match at home and obviously Calcutta for me is a special place, where I made my debut,” Bhupathi told reporters earlier this week. “There is so much amazing tradition of tennis here.”

It may have the legacy, but the South Club of 2019 is not the institution it once was. The 12 grass courts have been halved to six to make room for hard and clay courts. Bill Tilden-certified centre court has long been demolished to house a hardcourt and a swimming pool. The transformation is a result of Davis Cup’s (and tennis’, in general) evolution. The seeds were sown during the 1993 tie against Switzerland, when Marc Rosset bellowed: “Is it grass or is it something for the cow to graze?”

The rain on the match eve had flooded the court. “All the ballboys and the maalis worked whole night to make the court playable. We didn’t have a super-sopper then,” South Club secretary Giri Chaturvedi recalls. “Towels came to our rescue and a big bathtub. Next day, the court became very slow and low, and Rosset was a tall man.”

Moreover, serve and volley gave way for baseline slugfests. Courts were slowed down to please both broadcasters and players. And when the Big W itself had to change, South Club never stood a chance.

But the club’s fall in Indian tennis’ pecking order has also coincided with Kolkata gradually losing its ‘blue chip’ status. The likes of Roy Emerson and Ilie Nastase were regulars at the club in the days when all major airlines — Pan Am, British Airways, Cathay Pacific — touched down in Calcutta. International flights from Kolkata to Europe are now few and far between.

Nostalgic pangs for grass and presumption about visitors’ weakness brought Indians back to South Club. The Italians though humbled the hosts 3-1 in two days of World Group Qualifiers action. It seems the players, much like the venue, weren’t ready for the challenge. “We don’t have those seating arrangements – at least a 4,000-seater stadium is required to host a Davis Cup tie. So the AITA requested the ITF to permit a lesser number of people to sit in the stadium,” says Chaturvedi. “The ITF agreed. The makeshift stand accommodated 3,000 spectators.”

But South Club and regulars are content that the venue and the honour roll members are having their deserved moment in the sun.

“Forget the Davis Cup part,” says Piperno. “No club in this city, in this state or in India can claim the sort of success that we, and South Club, have had in producing players who represented the country.”