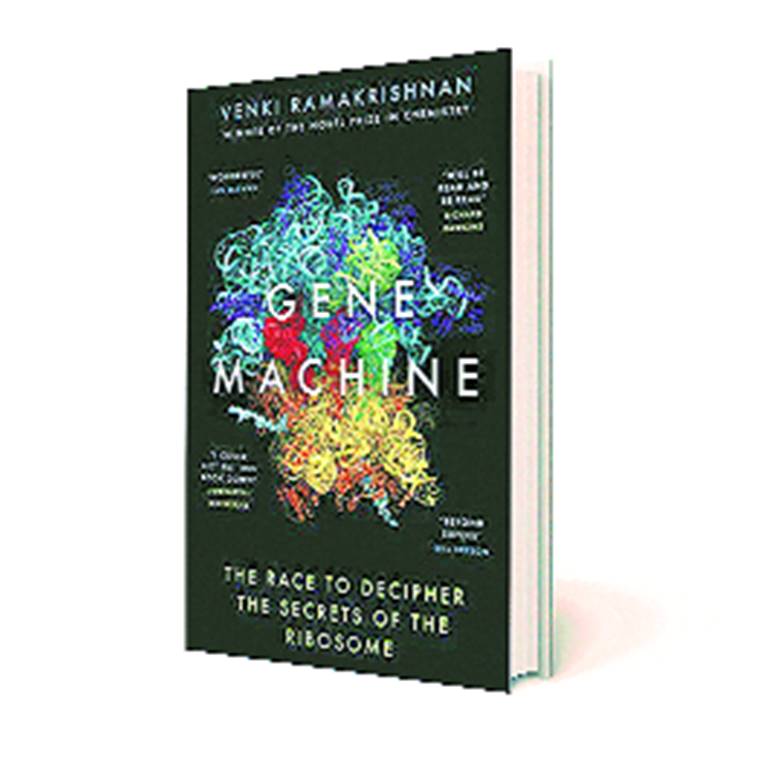

What led you to write this book (Gene Machine, HarperCollins) about the race to unlock the structure of the ribosome?

It had a peculiar drama to it, because of the characters involved and how the race (to decode the ribosome structure) unfolded. Even while it was happening, I thought this would make a good story someday. There was also the business of trying to explain what this ancient molecule was, why it was important, and why all these people spent their lives studying it. I also thought that my story as an outsider, who didn’t go to the best universities for most of his education, and somehow managed to find himself in the middle of this big quest was interesting.

Did you ever fancy yourself a writer?

As a child in Baroda, Gujarat, I did fantasise being a writer. But, growing up in India, nobody really encourages you to become one. In a sense, I became a scientist by default. If the book does well, then I would like to write other popular science books. Maybe, that would be my career after I retire.

You write elsewhere about how your mother did a PhD in psychology in the US, on your father’s insistence. That must have been a fairly radical thing then.

It would be remarkable even today for a man to say, ‘I’ll take care of this three-year-old, you go off to the US and get a PhD’. But in the 1950s, for an Indian male, or a male anywhere in the world, it would have been radical. That says something about how my father valued my mother as an intelligent person. But he was very autocratic in his own way. Although, he became less and less so later on. He did all the cooking and nursed my mother when she was in poor health before she died.

Were you a good student?

I was good but not exactly a model student. At times, I goofed off, cut classes. In the middle years, perhaps because of puberty, I lost interest in performing during exams. I would read a lot, but not necessarily textbooks. And so, I slipped from the top of the class to the bottom third. One year, I barely passed. As I approached the final years of school, I realised that unless I changed, things were not going to work out. And I did change.

Was science something you always wanted to do?

I had a very motivating science and math teacher, who made me feel, ‘Oh, this stuff is actually interesting’. But I wasn’t clear about what I wanted to do. I had written the IIT (Indian Institute of Technology) entrance examination. If I had gotten into an IIT of my choice, I would have gone and become an engineer. I didn’t have this big driving vision of becoming a scientist. Because of my mother’s encouragement, I took the National Level Science Talent Search Examination, which was a big deal in those days. Some of the best students would reject IITs to become a national science scholar — unlike me who did it because I didn’t have a choice. When I got it, it was almost like a sign — I didn’t get into engineering, but it looks like I might be good at pure science.

What were the disadvantages of being an outsider in Western science — first in the US, and now in Cambridge, UK, where you live? What did it enable?

I have been an outsider since the age of three. I was a Tamilian in Baroda, where my father worked. The first memory of school I had is of watching kids play and not understanding a word. The disadvantage of being an outsider is that you feel that you don’t fit in. I am not talking of the obvious like racism or prejudice, which are just facts of life. As an outsider, you often feel that maybe you are not as good. But the advantage is that you often have a fresh view of a field, you are not as affected by current thinking or dogma. You are willing to say, ‘Why can’t we do it this way?’

There has been a spurt in pseudoscience in India, with outlandish statements being made at important forums. Does this worry Indian scientists?

I don’t think it affects those who are in science directly, but it does affect them indirectly by changing the public perception of science. It is one thing for a few crackpots to spout off nonsense — that happens everywhere — and it is another for people in authority to do that, and at a big forum like the Indian Science Congress. Then it needs to be forcefully rebutted — by saying why and how it is wrong. That it is not science, because science demands testable evidence. When it is reported in The New York Times or the BBC, that an Indian vice-chancellor said Indians knew stem cell biology because of Gandhari or something written in Mahabharata, it makes India look bad. Just for that reason, people in authority should put a stop to it.

How could the Indian Science Congress be done differently?

It is a very large event, and, therefore, unmanageable. They need to make it smaller, have expert committees that select the talks; each talk should be vetted by someone who knows the field. Even, in spite of that, if a crackpot gets through, as soon as he starts spouting off, it is the job of the chair to shut down the talk and eject him. I also disagree with the business of inviting VIP scientists and shepherding them away, only getting a talk from them, not allowing them to mingle/engage with the attendees. (Fixing the congress) is not an insoluble problem, but they have to want to change it. I don’t know if they want to.

This is the age of strident nationalism. How does it affect science?

Science is always dependent on the free flow of ideas that generate in one place and migrate to another. India invented positional notation for numbers, which migrated through the Middle East to Europe, and changed mathematics. Quantum mechanics was invented in Europe but developed in the US. Science is global, and being narrowly nationalistic is harmful not just for science but for the country.

What have been the advances in ribosome research since you got the Nobel in 2009?

We know a lot more about the mechanism of action of the ribosome, how antibiotics bind to it. We know about ribosomes from a lot of organisms, including humans, mitochondria, parasites. They all look fairly different from each other. We are trying to understand how ribosomes are regulated by the cell, how they are hijacked by viruses, and so on. A lot of fundamental questions remain: How does the ribosome even originate? What does the primordial ribosome look like? How are they turned on and off?

How will modern science deal with the ethical challenge of gene editing?

The science community is very active on this. The Royal Society, the Academy of Sciences in the US, the Chinese Academy of Sciences got together and agreed that there should be a common set of principles. We are also going to involve many of the other academies. It is an international problem. How to decide how to go forward, what sort of things are okay to do and what sort of things might never be. We have to get countries to enact a common set of regulations so that you don’t have people going off to the science equivalent of tax havens to do what they wish.

What is the worst thing about the Nobel?

It can be distracting. People assume you are a genius who knows everything. You have to guard against that and not pontificate about everything. Some retired Nobel laureates spend all their life flying around, (getting) wined and dined. That is the post-Nobelitis syndrome.