Nadine Labaki, 45, actor-director, is used to being looked at: her beauty has that impact. What she has also achieved in the past 15 years since she became a filmmaker, is to make people look at her work, which uses a mix of personal and political to tell us stories with meaning and resonance. Her films are set in the volatile Arab world, but they could represent any region where conflict, warring religions, and the refugee crisis, is an ongoing reality.

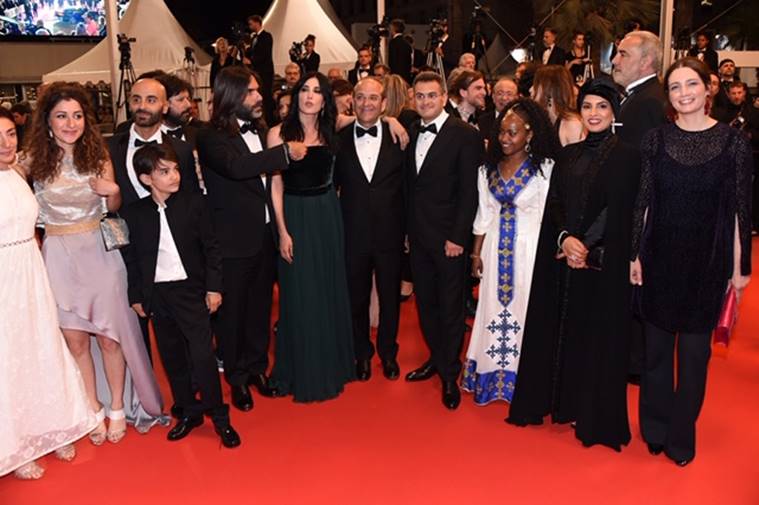

Her first and second outings, Caramel (2007) and Where Do We Go? (2011) were striking comments on how people riven by differences could learn to agree. Her third film, Capernaum, took Cannes by storm in 2018. Next month, it will compete in the Best Foreign Oscar film category. Capernaum is about a boy and how he negotiates, with an amazingly doughty spirit, the kind of crippling challenges which would stop your average adult in his tracks. There are times you feel emotionally manipulated — a little boy and a baby in difficulties will do that to you, but there is no doubt that the film leaves a strong impact.

Labaki believes cinema can change things, and her voice carries. Excerpts from an interview on the sidelines of the recent Ajyal Film Festival in Doha:

Your debut Caramel (2005) was a first-of-its-kind film from the Arab world. How did you come to your cinema?

I’ve always wanted to make films since I was a child. I grew up in the war (the civil war in Lebanon), and films were a very important part of my life, as they took me away from living behind shelters and sandbags. Through films, I started living a different reality, and I understood that in order to create different realities, you could be a filmmaker.

Of course, in Lebanon, with no film institute, no industry, I didn’t know where or how to start. It was a struggle to make a film, whether you were male or female, because the war had destroyed everything.

Between your second film Where Do We Go, and this one, Capernaum, there has been a significant gap. What was happening in between?

I was growing as a person and waiting for the idea to start growing. It starts always as a theme, and grows into something I eagerly want to talk about.

You began working on Capernaum in 2013 and it took five years to release. How did you go about it?

Zain (the young protagonist) is a Syrian refugee living in Lebanon in difficult circumstances since he was eight. Luckily now, he is much better, he is going to school. All the ‘actors’ are from real life, so to speak. This is what we spent all our time in, the research. We went to the streets, the slums, the prisons, the courts, the neighbourhoods, talking to children, parents, lawyers, judges, all the institutions, the social workers, and we started looking for the right ‘actors’ and interviewing them. I didn’t want to ‘imagine’ this story. I didn’t feel entitled to imagine a life I’ve never lived.

We wanted to be very careful and meticulous with the research, trying to understand the problems everyone faced. Yes, it was a long process but we needed the time to be fully immersed in that reality.

Is it difficult to maintain a non-judgmental tone when you are privileged by circumstance and class?

You have to stay true to yourself. Capernaum started with frustration at the terrible condition of the refugees, and it had to be a film which expresses the voice of the children. It had to be for them to say ‘this is our situation’. I had to become the platform, the vehicle, and not intervene. Sometimes I admit I was judgmental. I would go into an apartment and see the kids alone, hungry, with nobody to take care of them. When you know children are dying like this every day, falling off balconies, sticking their fingers into sockets, I would wonder how the parents could do this. I would talk to them to try and understand why. Fifteen minutes into the conversation I would be forced to stop judging. It was important for me to find that place, of not judging, just observing and being empathetic.

In the post #MeToo world, do you think this is a good time to be a woman and a filmmaker?

Absolutely. It helps to talk, to put the problem out there. It is the way to heal.