In the tiny, charming fishing villages along the coast of the Arabian Sea in southern Kerala, the story goes that it’s famed mineral-rich black sand piqued the interest of the Germans when they noticed the unusual thickness of the ropes shipped from the southern Indian coast. Those days, the women, who worked in coir factories in these coastal villages, had the habit of mixing black sand, without knowing it’s worth, with coir to lend it strength. When the sand was disseminated, geologists chanced upon the presence of rare earth minerals like monazite, ilmenite, rutile and zircon which find application in the production of atomic fuel.

Thus began extensive beach sand mining operations in this stretch of the Kollam-Alappuzha coast, a fragile ecological territory, mainly by two public-sector firms, the Indian Rare Earths Limited (IREL) under the Centre and the Kerala Minerals and Metals Limited (KMML) of the state government. Despite the concerns of local communities about coastal erosion and bypassing critical norms of the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ), the mining activity continued. In a state with a rich history of potent environment movements, this beach sand mining, surprisingly, found little resistance. Until now.

An indefinite hunger strike that began on November 1 last year by a motley group of villagers in Alappad, a fishing settlement wedged between the Arabian Sea and the Kollam-Kottapuram Waterway against the beach sand mining, has rattled the state government, perhaps for the first time. A video posted on the popular mobile platform TikTok by a Class 12 student from the village, in which she relayed her community’s fears of their homes being wiped off by effects of large-scale mining, went viral in the state prompting it’s leading film stars to come out in support of the campaign.

Earlier this week, shaken by the strong public support the protest has garnered, the government held talks with the agitators and agreed to temporarily suspend beach-washing, an act of separating minerals from the sand right at the coast. The administration also said it would constitute an expert committee to submit a report on the mining activity in the area. But nothing less than a complete stop to mining is acceptable, the protesters reiterated.

‘Island has shrunk, fish have gone’

On a pleasant morning last week, small groups of mostly youngsters could be seen milling around a modest thatched hut that serves as the venue of the ‘Save Alappad’ protest in the village. A little blackboard slung outside recorded the duration of the protest. The hut sits right in front of a temple dedicated to a goddess and has it’s back to the beautiful, azure landscape of the Arabian Sea. On the sandy coast, under the shade of coconut trees, men sat in huddles smoking beedis and playing cards for money.

Outside the protest venue, 72-year-old K Chandradas, a former fisherman who’s assumed role as the chairman of the ‘Save Alappad’ protest committee, sat on a plastic chair, his face steely. If he has briefed dozens of reporters on the demands of the committee and the fears of the people about mining, it clearly didn’t show on his face. Measuring every word carefully, Chandradas, whom everyone calls ‘achan’ (father) out of respect, spelled out why it’s a do-or-die situation for his village and others on the coast.

“The current generation of people wouldn’t believe that verdant green paddy fields existed in Mookumpuzha, Parakkada and Kuzhithura areas of Alappad panchayat. But they did, at one time. Today, they are lost to mining,” he said.

He recounted more losses.

“We have lost our beaches due to repeated incursions by the sea. Lithographic maps from the 50s, compared to today, will show you how the village’s size has shrunk from 89.5 sqkm to 7.6 sqkm. We were number 1 in availability of fish, today we are at number 7. In olden times, we used to practice a unique ‘kambavala’ mode of fishing which involves using the coast to spread the net. Today, we are forced to spend thousands of rupees on fuel and large boats for deep-sea fishing. These are all the outcomes of mining,” he said.

The authenticity of the lithographic maps and the impact of mining on change in modes of livelihood are certainly subject to debate. But if there’s one definitive fact that can be taken away after a visit here, it is that the coast is rapidly shrinking and how. Past studies by experts and satellite maps are evidence to prove how large tracts of land in these villages on the coast have been lost out to the sea over the years due to a variety of reasons. Irresponsible mining and beach washing can only exacerbate the problem, they show.

A study by scientists of National Centre for Earth Science Studies (NCESS) on ecological hotspots along the southwest coast of India notes erosion at the “downdrift side of harbour breakwaters and groins” as well as the seawall end, mining sites, fishing gaps and downdrift side of mud bank. In fact, the report mentions Vellanathuruth, located in the northern end of Alappad panchayat where IREL has finished excavations, as one of the erosion sites.

KV Thomas, one of the two authors of the study now retired from NCESS, told indianexpress.com, “The beach is an asset of the community. That it’s lost today is the pivotal issue. The community realised it’s value only after it was lost. It was not lost in a day, but over years.” He added that sediment budget studies are necessary to evaluate the amount of sand that can be mined from the coast. “If mining continues at this scale, the problems will only increase.”

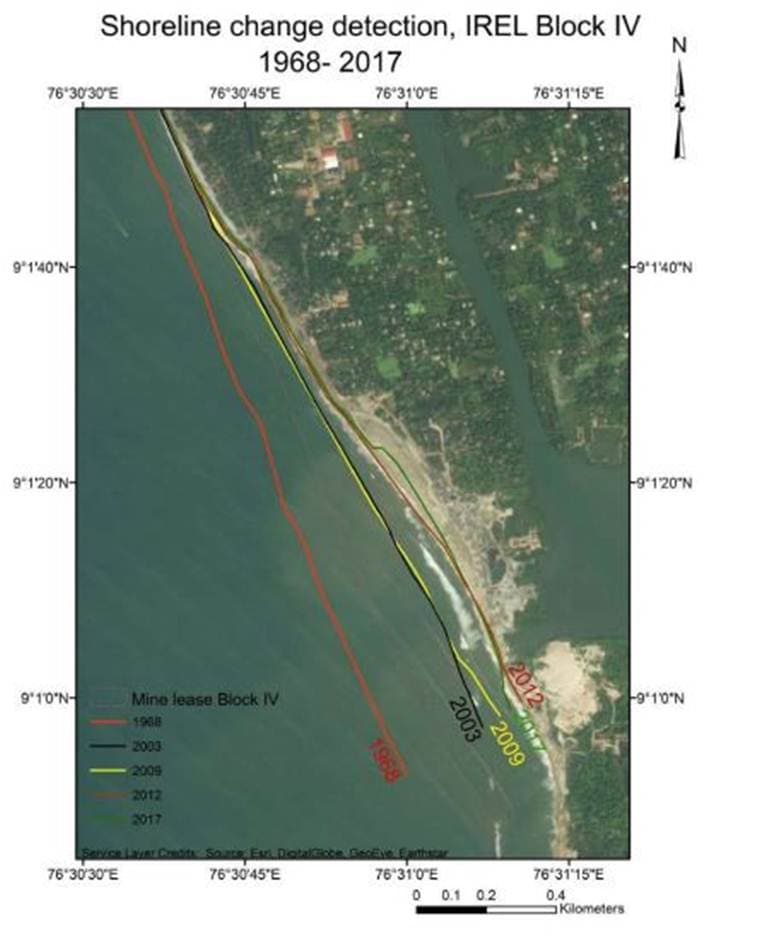

Similarly, a satellite map used in a draft report by the National Institute for Interdisciplinary Science & Technology (NIIST-CSIR) submitted to the IREL, shows the changes in the shoreline from 1968-2017 in an area leased out to the company for mining. The photograph clearly points to how significant tracts of the coast have been subsumed by the sea over the years.

Muralee Thummarukudy, a Kerala native and chief of disaster risk reduction at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), sharing a bunch of publicly-available satellite photos of the mining area in a Facebook post, wrote, “It’s because of green vegetation and water that people settled down in areas like Alappad and Ponmana. Post mining, there must be a lot of salt water in this area. Even if sand is refilled in these areas after mining, the previous state of housing is not possible. Don’t even think of agriculture..”

“A region which lies sandwiched between the sea and the backwaters, strengthened by nature over thousands of years, has been made fragile…the question on my mind is not whether this region (Ponmana) will get swallowed by the sea. It’s how and when it will get swallowed. That’s why the concerns of the people of (neighbouring) Alappad have scientific justification,” he added.

In fact, a drive along the coast helps understand the gravity of the situation. At Vellanathuruth, the southern end of the Alappad panchayat, giant earth-boring machines are at work, scooping copious amounts of sand. A small temple sits amid the giant mounds of sand. Just metres away, a part of the seawall lies fractured, indicating the site of sea washing. A plain narrow concrete road separates what’s left of the beach from the mining site on the other side. Further southwards, the Panmana panchayat begins, where KMML controls extensive mining sites. In this region, as far as the human eye can travel, only sand mounds are visible along with the heavy machinery of the miners. Where once extensive vegetation stood, as Thummarukudy pointed out, white, barren tracts of land remain.

That coastal erosion can invite the wrath of the sea in the form of tsunamis and swell waves directly on their homes is not lost on the people here. It’s not for nothing that such fears warrant serious attention. In 2004, the Indian Ocean tsunami claimed 143 lives in Alappad village alone. To this day, locals here have vivid, horrifying memories of having watched waves as high as a coconut tree. Throughout Alappad, dozens of homes out on the coast lie dilapidated, some with their roofs wrecked, others with deep fissures on the walls. Over 5000 families had to be displaced from this part of the coast after their homes were breached by the sea. Even today, the rumble of an angry sea at night is a cause for worry for many.

“Where else would we go? This is where we were born and this is where we want to die. We stand strongly with the protest,” says Indrani, sitting on sand behind her home cleaning brass lamps. Sajeesh, a policeman and a resident of the village, adds, “If there’s another tsunami, our village will disappear.”

Cibi Boney, a ward member of the Alappad village panchayat and one of the few local public representatives here to have supported the protest, told indianexpress.com, “The mining companies are deliberately violating rules by taking more sand above permissible limits. We asked them not to do sea washing. They still do it. This is a question of our survival. Why should we pledge allegiance to these companies who are hell-bent on destroying our lives?”

Boney, a member of the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP), an ally of the Congress, is part of the minority in the Left-ruled panchayat. So far, the panchayat, with clear political leanings, has resisted any move to shut mining in the village. The two times the panchayat council met, the issue did not come up on the agenda, she said.

‘Sea wash is scientific, done by locals’

Industries Minister EP Jayarajan told reporters on Thursday that the protesters’ demands of putting a stop to beach washing, repairing broken parts of the seawall and forming an expert committee to do a study have been accepted. But stopping all mining works was not, he said.

“These are Kerala’s two large public-sector units. Can anyone be okay with shutting down these companies. I asked them to think. Should such a mindset be encouraged? It’s unfortunate if the protest continues,” he said.

On behalf of the IREL, PR Deshpande, chief general manager (HRM), told indianexpress.com via email, “The allegation that extensive mining by IREL has led to severe coastal erosion is not true. IREL is a Central PSE under the administrative control of a sensitive department like the Department of Atomic Energy. Collection of sea wash is as per proper rules and regulations. In fact, the activity of sea wash collection is carried out by the locals of the area, who have been engaged for this purpose by IREL.”

“It is impossible to imagine that the locals would work against their own interest by indulging in any activity which would directly cause coastal erosion. In fact, their engagement provides the right check and balance in this regard. It is also reiterated that the sea wash collection (a replenishable source) is being carried out based on the scientific study done by NCESS (National Centre for Earth Science Studies), Thiruvananthapuram on sand accretion and budgeting. Based on the study report by NCESS, the Mining Plan for collecting beach wash mineral sand per annum has been duly approved by IBM (Indian Bureau of Mines) and AMD (Atomic Mineral Directorate).”

He also denied reports that IREL was mining more sand above prescribed limits. He wrote, “IREL is adopting scientifically proven methods for extraction of minerals. IREL is carrying out two methods for extraction of minerals i.e. winning from sea wash collection and inland dredging at Alappadu Village. Major stretch of coastline i.e. around 16 kms of Alappadu Village is totally protected by sea wall constructed by the Government of Kerala more than 50 years ago. Sea wash collection is being done at the southernmost end of Alappadu Village in a stretch of around 500-meter length where sea wall is kept open for the purpose.”

Officials of KMML did not respond to calls and a detailed email questionnaire.