In an international career of five years, Mike Brearley played 39 Tests and 25 One Day Internationals, averaging 23 in the longer format and a little less in the instant variety. These unremarkable figures notwithstanding, Brearley has a permanent place in the game’s history. Arguably among the front-rowers in the pantheon of cricket captains, Brearley captained England in all but eight of the Test matches he played, winning 17 and losing only four, and led them to a second place in the World Cup.

Of course, Brearley was helped by having Bob Willis, Ian Botham and Alan Knott at their prime, but it could also be said that he nurtured their skills along with others such as the young David Gower and Graham Gooch. The former Australian quickie Rodney Hogg once commented that Brearley had a “degree in people”.

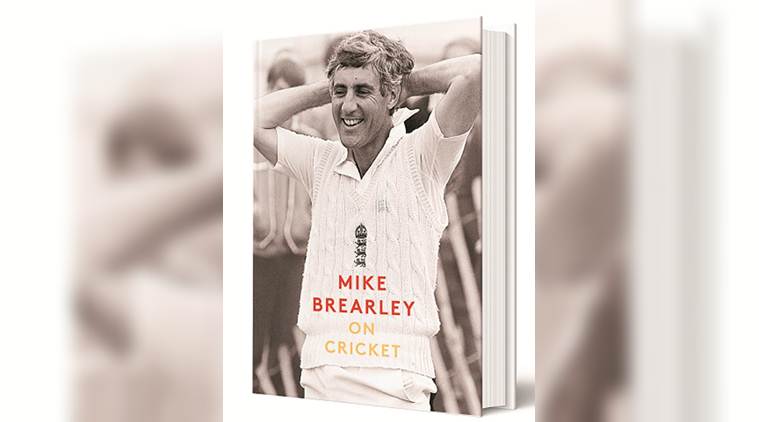

Brearley has a degree in philosophy from Cambridge University and had lectured on the subject at the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne before becoming an international cricketer. After retiring from the game, he became a professional psychoanalyst and was president of the British Psychoanalytic Society. Truly one of the game’s top minds, his written word is taken seriously. His last book, On Form, was the Times book of the year in 2017.

His latest book, On Cricket, traverses 50 years of the sport with palpable intellectual curiosity. It’s the work of a person who delighted in the aesthetics of the sport even when he was competing. Brearley writes that he couldn’t help but derive pleasure from Greg Chappel’s batting even while he was setting fields to stop the rampaging Australian. At another point, he writes that, “I once stood at extra cover at Cambridge to the great Gary Sobers. Apart from my alarm at the likelihood that he would middle one of his powerful off-drives straight at me, I have a vivid image of that afternoon 50 years ago of the style, power, classicism and the freedom of his arms and hands, and recall it better than I remember most of the pictures I have seen in art galleries”.

In less than 400 pages, Brearley opens up on some of the issues that the game had to confront during his playing days — the ban on South Africa, Kerry Packer, some of the greats with whom he shared the field — Viv Richards, Bishan Singh Bedi, Michael Holding, the rights and wrongs of modern day cricketers — Virat Kohli, for example, and, the general direction in which the game seems to have headed.

The essays are enriched by Brearley’s training as a philosopher and psychoanalyst. His understanding that people are drawn to the game by its aesthetics, or by the mastery of their heroes, is compelling. His words — “We become mini-Federers when we watch Roger play a cross-court forehand, or mini-Warnes when Shane bowls a perfect leg break or mini-Chappels, when we see Greg playing a back-foot stroke of his hips with sumptuous elegance. It’s not that we are under illusion. We know that we are not Federer. But we enter the mind-set. We know they are beyond us, but for a moment we have a sense of its possibility” — would strike a chord with anyone who has played sport, even though that might have been at the most modest level.

However, in times when the slam-bang version of cricket rules the roost and commerce is a dominant motif, it’s somewhat difficult to appreciate that the urge to replicate a Sunil Gavaskar — or a Virat Kohli for that matter — cover drive, is what draws youngsters to the game. Brearley makes his preference for the longer variety evident. For instance, in an essay that draws from his conversation with Michael Holding — it’s aptly titled ‘Whispering Death’ — Brearley talks about the West Indian great’s reluctance to be associated with T-20 cricket. “But when he was told that the aims would be to find Test players as much as short-game players… he had agreed to play a part. Who knows, maybe this will be the beginning of a revival and we’ll see a new batch of Holding Roberts and Marshalls gracing Test cricket once again”.

Is the instant variety of the game bereft of aesthetics, then? The only semblance of an answer is in the essay on Kohli. Brearley makes his admiration for the Indian captain obvious — “Kohli has a stroke to be seen in his test innings as well in the shorter forms of the game. This is the top spin drive… Instead of letting the ball come to him, he reaches forward in front of his left leg making contact with the ball well ahead of himself and sooner after it has pitched, with his wrists he almost plays what is almost a hockey shot… It requires speed of vision and dexterity of wrists and hands”.

Brearley, in fact, concludes On Cricket with one of the rare sentences of pessimism in this collection of essays.

“I enjoy T20 cricket and the innovations it has given rise, while at the same time being alarmed of its proliferation and the threat it poses to international [sic] — particularly Test — cricket”. It’s difficult to not empathise with that feeling, more so after reading On Cricket.