Research by scholars from University of Chicago, UC Berkeley and London School of Economics backs Niti Aayog suggestions for civil services.

In a recent report, the NITI Aayog recommended reducing the upper age limit for civil services to 27 years. Indeed, recent research by scholars from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, UC Berkeley Haas School of Business and the London School of Economics suggests that bringing down the upper age limit at the entry level in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) is likely to boost bureaucrats’ performance by extending the service span of officers and improving their career incentives.

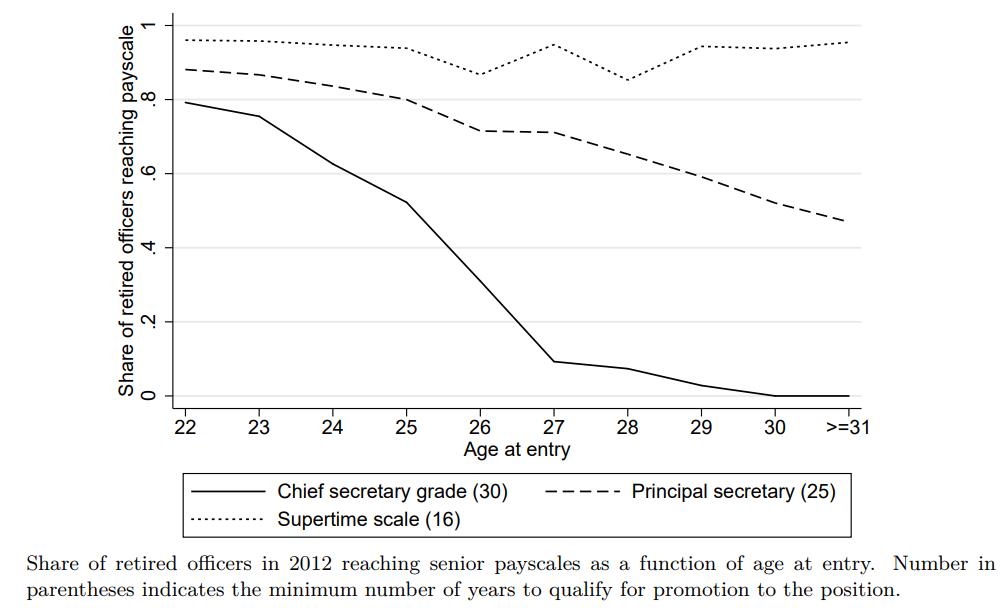

The argument is simple: since career progression in most civil services – and the IAS is no exception – is primarily time-based, those who enter at an older age will have fewer opportunities to reach the top pay scale. For example, to qualify for the chief secretary level positions, officers have to typically serve at least 30 years. With a retirement age of 60 years, this implies that an officer who enters the service at the age of 30 will have virtually no chance of ever making it to the top of the civil service.

This will affect the performance of civil servants in several ways. First of all, those who enter older are more likely to be discouraged – given the seniority-based promotion constraints, they will not make it to the top even if they work hard enough. Knowing from the time of application that one’s performance has little bearing on making it to the top will also affect the quality of civil servants who decide to join in the first place.

Reducing the upper age entry limit will thus help expand the career span of civil servants and ensure that hard work pays off by allowing more entrants to compete for the “glittering prize” – the apex-level positions in the civil service.

This is not just a conjecture. We tested this idea by crunching big datasets. Drawing on personnel records of IAS officers, we confirm that those who enter older are indeed less likely to reach the top pay scale. In Figure 1, we computed the share of retired IAS officers who reached the top pay scale as a function of their entry age. While nearly all IAS officers reach the supertime scale (requiring a minimum of 16 years of service), older entrants are less likely to reach the principal secretary (minimum 25 years), and chief secretary scale (minimum 30 years). While 80 per cent of those who join IAS at 22 are able to retire at the chief secretary scale, the chances are close to nil for those who enter the service at 29-30.

Figure 1. Reaching the top pay scales and entry age

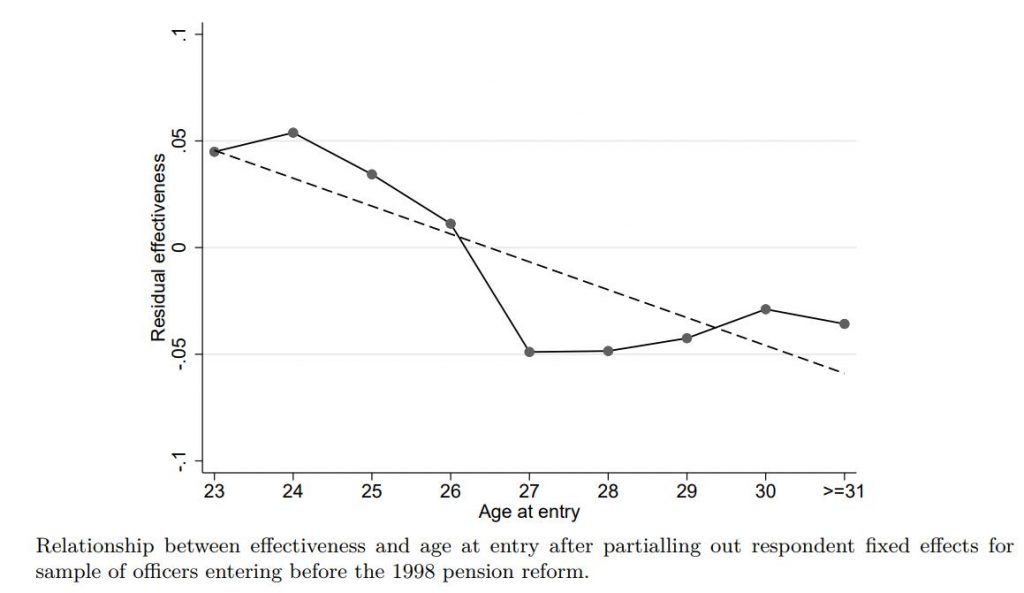

Consistent with our hypothesis, we find evidence that older entrants tend to have lower performance levels. To assess performance, we collected a large-scale survey on the perceived performance of civil servants. In Figure 2, we show the average effectiveness score of these civil servants as a function of their entry age – larger scores mean above average performance and lower scores indicate below average performance. Indeed, older entrants are perceived as less effective. Interestingly, the pattern looks strikingly similar to the decline in the promotion odds for reaching the top pay scale – it is exactly when the “glittering prize” is out of reach when the performance drops.

Figure 2. Perceived effectiveness and entry age

These results thus resonate with the recent recommendation on reducing the entry age limit: taking our data at face value and given the current promotion system, a cap on the entry age at 27 would ensure that all entrants have a decent chance to compete for the top positions.

Of course, limiting the entry age at 27 – by barring many motivated and bright older entrants to serve the nation – is likely to be an unpopular policy. Indeed, the entry age of the “Steel frame of India” has moved from what was limited to 21-24 before Independence in the Indian Civil Service to a 26 years for general entrants in the 1970s, 28 in the 1980s and 1990s to 30 in the 2000s. The current age cap is 32 years. The pressure for inclusion is a likely reason why earlier calls for reducing the entry age (such as in the Baswan Report) were not followed through.

Luckily, there are a set of alternative policies that could equally help to boost career incentives. For example, allowing older entrants to retire later is likely to have similar positive effects. In 1998, for example, the retirement age for IAS officers was extended from 58 to 60. Again, we looked at the data and found that older entrants – especially those previously capped out from reaching the top – are suddenly showing a substantial growth in their performance after the pension reform, consistent with greater incentives. Other policies such as fast-tracking career progression, fixed tenures as opposed to fixed retirement age, and allowing lateral entry are all likely to be effective in boosting performance – many of these are being discussed by the NITI Aayog. Time will tell whether the entry age limit for IAS, as well as the wider civil services, would continue to go up (as has been the norm) or would it finally be narrowed down.

The author is Assistant Professor at the Berkeley Haas School of Business, and has a PhD in Economics from LSE.

ThePrint’s YouTube channel is now active and buzzing. Please subscribe here.

- 14Shares