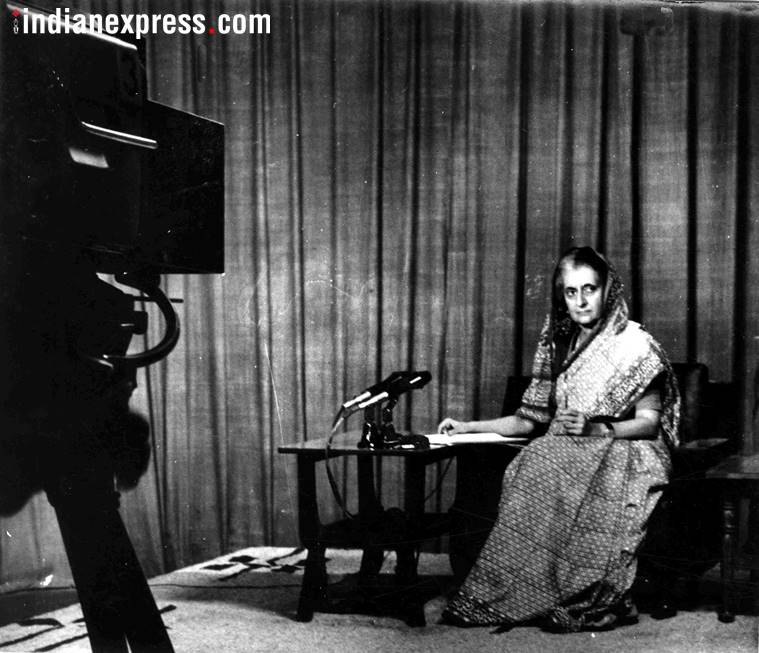

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi addressing the nation from the Doordarshan studio during Emergency Express Archive. Express archive photo August, 1975″

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi addressing the nation from the Doordarshan studio during Emergency Express Archive. Express archive photo August, 1975″

I fear Professor Gyan Prakash of Princeton University has defeated his own purpose by labelling his outstanding work, Emergency Chronicles. The chronicles themselves are fluently and persuasively recounted as a narrative history of the awful excesses inflicted on individuals and communities by and during the Emergency. But his larger historiographical objective gets obscured by his subtitle that describes Indira Gandhi’s actions in the 21 months, from June 1975 to January 1977, as “Democracy’s Turning Point”. As he himself ultimately concludes, “a limited view of the Emergency” as the act of one wicked woman “prevents an understanding of its place in India’s historical experience of democracy”. Prakash, thus, takes it upon himself to place the period in the larger context of the kind of Constitution we gave ourselves, and, the continuing rationale for the draconian laws we imported wholesale from our colonial past. Prakash situates the Emergency firmly in the context of the framing of the Constitution and what he calls the “afterlife” of the Emergency. For while we need, as a nation, to never forget, and, from time to time to re-remember, the horrors of that period, the fact is, as Prakash pithily sums it up, the Emergency and its excesses were “almost lawful but not quite” (p.170).

The Emergency was not “a momentary distortion”, nor can those grim days be “sequestered as a thing in itself” (p.375). Oppressive colonial laws used for the suppression of the freedom movement, such as those relating to preventive detention and sedition, were bodily incorporated into the governance of post-Independence India and sanctified by the Constitution, particularly through its provisions for the declaration of a state of Emergency.

Prakash traces this to Dr Ambedkar’s deep concern over the “grammar of anarchy”, the “post-War turmoil” and the “violence of Partition” that made the founding fathers, from Ambedkar to Nehru, “craft a powerful state that would secure national unity” (p.378). Nehru and all his Congress Working Committee colleagues including Sardar Patel but excluding the two prominent Muslim members, Maulana Azad and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, overcame Mahatma Gandhi’s principled objection to Partition by stressing that India would disintegrate if, in WB Yeats’ famous words, the centre cannot hold. The Cabinet Mission’s last offer, accepted by Jinnah and endorsed by the Maulana, of a weak centre in exchange for postponing for a decade a referendum on Pakistan, was unacceptable to an overwhelming majority of the CWC. Because the imperatives of integrating nearly 600 princely states into the Union and resisting the Muslim League’s relentless machinations to promote the Balkanization of India, could only be achieved by a strong central government armed with all the powers necessary to secure and maintain the unity of the nation.

The Azad/Khan objections were essentially focused on the tragic vivisection of the subcontinent’s massive Muslim population and, therefore, to be forestalled at any cost. Jinnah and a distressingly large majority of India’s Muslims failed to see this and fell for the siren song of Partition, whatever its adverse consequences for the Muslim community they claimed to champion. As for Nehru, Patel and eventually even Gandhi, these deleterious consequences had to be put in the balance of living with the first government of free India, losing the instruments of holding out against the formidable centrifugal forces lining up against it. That, too, backed by many elements of the fading imperial power led by Winston Churchill. We had to have a strong central government even if that meant conceding Pakistan.

Additionally, as stressed by Prakash, Dr Ambedkar, “convinced that Indian society lacked democratic values” (and who could dispute that?) placed his “belief in the reconstitution of society by politics. Accordingly, he wrote a Constitution that equipped the state with extraordinary powers” in the expectation that “the state would accomplish from above what the society could not from below” (p.377-78). Ambedkar and Nehru, fully backed by Sardar Patel, then joined hands to rebut “critics in the Constituent Assembly [who] repeatedly raised [their] voices against emergency powers and the elimination of due process”. They “successfully argued that the fledgling state’s executive needed extraordinary powers without judicial interference to deal with exceptional circumstances” (p.188).

That, rather than Indira Gandhi’s alleged subversion of judicial institutions, is what explains the repeated judicial exculpation of the declaration of the Emergency and the horrors that followed. As chronicled by Prakash, these exculpations came not only when Indira Gandhi ruled but also after the Janata government took office. Thus, Justice VR Krishna Iyer on 24 June 1975, a day before the declaration of the Emergency, “granted a stay of the Allahabad High Court judgement” that nullified the Prime Minister’s election and banned her from even contesting electoral office for six years (pp.158-59); there could be no challenge to the proclamation of the Emergency because “the Constitution itself had left the judgement of the necessity for the Emergency by proclamation outside the law” (p.163); moreover, as “Constitutional laws were not declared dead but suspended” these “suspended laws let loose shadow powers and shadow laws” (p.167). Yet, the courts were left impotent to alter “sovereign” decisions on “what constitutes a state of exception” because the Constitution vested that decision uniquely in the Prime Minister’s “power as the sovereign authority” (p.342). The Emergency, and what consequentially followed was, in the words of the telling title of one of Prakash’s chapters, a “Lawful Suspension of the Law”! (p.162) And thus it was that the Supreme Court under Chief Justice AN Ray ruled as “valid” the 38th and 39th amendments that respectively barred “judicial review of the emergency proclamations and ordinances suspending fundamental rights” and placed Indira Gandhi’s election “beyond the judiciary’s purview” while “eliminat[ing] challenges to the election of the Prime Minister and the Speaker” (p.188-189). And in the notorious Habeas Corpus case, the Supreme Court “upheld by a vote of 4-1…the government’s position”. The “infamous” 42nd Amendment remains to a large extent on the statute books. The fact is, that since “the justices were reticent on the legality of the Emergency, MISA and the constitutional amendments”, this “foreclosed… a heroic judicial challenge to the executive” (pp.192-195). In short, the Emergency and its dreadful consequences might be described as “illegitimate”; they could not be called “illegal”. Their legality was written into the Constitution and the law.

Note that there have been nine non-Congress governments in the 42 years since the Emergency ended, and yet, as Prakash dolefully bemoans, “the Emergency enjoys an afterlife” (p.380). Sedition, preventive detention, AFSPA and even Emergency provisions still prevail; so, any strong government in India can still impose “a state of exception” through the “sovereign” exercise of its “extraordinary constitutional powers” (p.382). Prakash’s concluding words are that the deification of the “leader”, such as we see now in the BJP, constitutes, as foreseen by John Stuart Mill, “a sure road to degradation and eventual dictatorship” (p.383).

The nation stands warned. It can still save itself in 2019.