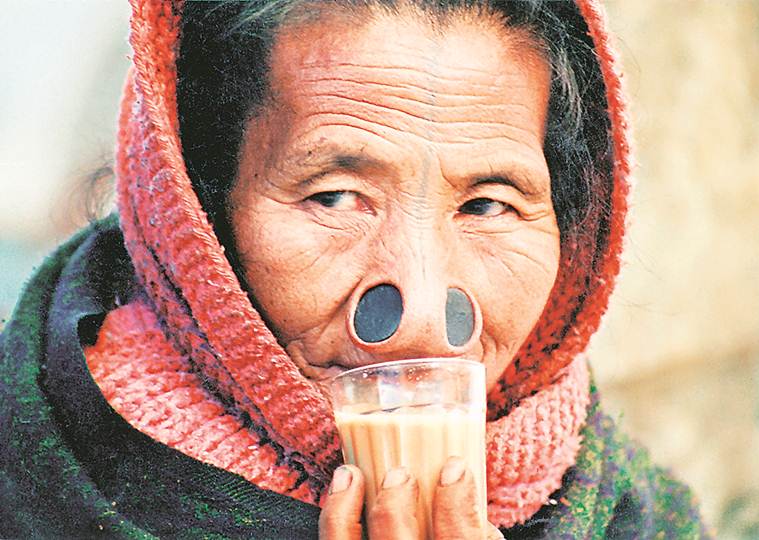

An Apa Tani woman from Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. (Photographs by Anu Mahotra)

An Apa Tani woman from Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. (Photographs by Anu Mahotra)

A four-hour road journey from Itanagar leads you to the Ziro valley, which is home to the Apa Tani tribe. They claim common ancestry with Abo Tani, who, they say, was the first human being on earth. It is with them that filmmaker and photographer Anu Malhotra began her quest to document tribal culture. Her 2000 film The Apa Tani of Arunachal Pradesh recorded the life and customs of the tribe. “I realised how strong community bonds are important to keep us rooted and secure, and how a sense of belonging can enhance our well-being,” she says, recalling the experience.

She shares the memories of that journey in her new book Soul Survivors, which also has photographs of the Konyaks of Nagaland and the nomads of Tibet. “We were blindly aping the West and a lot of our living heritage and culture was vanishing. We were losing our traditional wisdom, wise ways of life; I wanted to document and encapsulate these,” she adds.

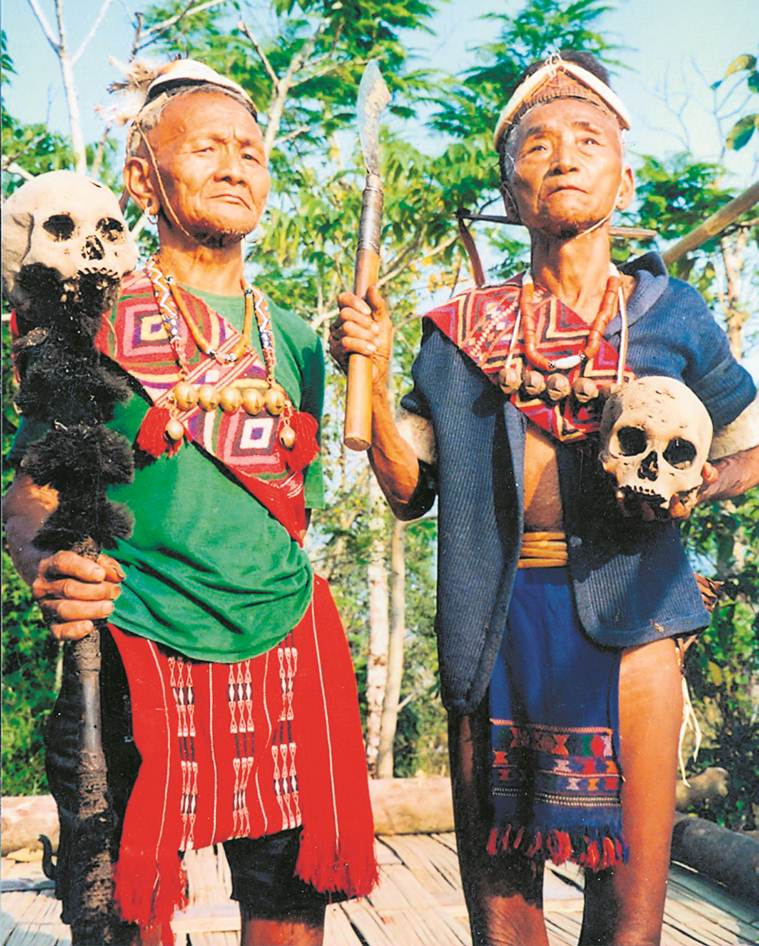

Erstwhile Konyak headhunters in Nagaland. (Photographs by Anu Mahotra)

Erstwhile Konyak headhunters in Nagaland. (Photographs by Anu Mahotra)

While documenting the “customary way of life” of the Apa Tani tribe made Malhotra realise the “importance of leading a physically active and outdoorsy life”, a year later, she was back in the Northeast to photograph the Konyak tribe in Nagaland. Described as “fierce headhunters” by Christoph von Furer-Haimendorf in his book Naked Nagas, Malhotra photographs the women in long skirts, wearing heavy brass and bead jewellery, and the men being trained in the morungs (dormitory) in Wanching village — getting acquainted with their ancestry and rituals, learning warfare, cultivation, wood carving, basketry and music.

“Traditionally, the Konyaks believed that the soul of a person lives in the nape of the neck while the spiritual being, a source of fertile potency, was in the skull, and that it could be transmitted to others. The means of acquiring such power was to behead one’s enemies,” writes Malhotra in the book. While the Tribal Council still resolves disputes and the decision of the Angh (the chief) is final, Malhotra adds that the Nagas are believed to be part of the great Mongoloid race that expanded through South East Asia, from North China, possibly about 10,000 years ago.

In the third segment of the book, the photographer has the nomads of Tibet, whom she encountered while travelling 1,200 kilometers across the south-western Tibetan plateau, towards Lake Mansarovar and Mount Kailash in 2002. “I feel privileged and nostalgic about having visited Tibet at a time when I could still experience some centuries-old traditions, breathe a freer air and enjoy the vast expanses as the nomads did,” writes Malhotra, reflecting how much of what she saw in Lhasa does not exist anymore. The Apa Tani society, too, is marked by an increase in migration and unemployment, and in Nagaland, it has become necessary to “reexamine the Naga customary laws and find out how the modern legal system and the village councils might work together”.