(Left to right) Saramma, Paru K, Sarada K, Janaki K V, and Yasoda Krishnan going for Aksharasagaram classes at Ayitti coastal village in Kasargod

(Left to right) Saramma, Paru K, Sarada K, Janaki K V, and Yasoda Krishnan going for Aksharasagaram classes at Ayitti coastal village in Kasargod

After scoring 98/100 and bagging a laptop from the Kerala government for her efforts, Karthyayani Amma, 96, is in a hurry. “I want to learn more… I want to learn English next,” says Karthyayani, now the poster girl of Kerala’s literacy programme.

Last week, when the Kerala State Literacy Mission announced the results of Aksharalaksham, its adult literacy programme, Karthyayani had emerged the top scorer among 43,700 candidates who sat for the exam in August.

Karthyayani Amma writing the Aksharalaksham literacy exam at Cheppad in Alappuzha in August. (Express Photo)

Karthyayani Amma writing the Aksharalaksham literacy exam at Cheppad in Alappuzha in August. (Express Photo)

Karthyayani is among 60,000 people in the state who have been initiated into the world of letters through over half-a-dozen literacy schemes run by the Mission. An overwhelming number of them are, like Karthyayani, elderly women who have never gone to school. Having struggled through a major part of their lives and now in their sunset years, these women, huddled together in community centres and anganwadis, are discovering a whole new world — the magical loopiness of the Malayalam alphabet.

“Why didn’t I go to school? Because I was too busy bringing up my children,” says Karthyayani. For several decades, the mother of six worked as a casual cleaning worker at half a dozen temples in Cheppad in Alappuzha district.

The state’s literacy drive of the 1990s didn’t spot her either. “The literacy preraks (grassroot-level volunteers who motivate people to attend literacy classes) probably missed me since I would be working all day and would be back only by 8 pm. Where is the time to study after that?’’ asks Karthyayani, who lives with her granddaughter in Muttam village in Alappuzha.

But in January 2017, when the Literacy Mission started a new survey to identify the unlettered, Karthyayani readily signed up. Her husband Krishna Pillai had died in 1961, her children were busy with their own lives and she was ready to lead her own.

Padmini Veliyan participates in the tribal literacy programme in Thondarnadu panchayat in Wayanad district. (Photographs: K Shijith)

Padmini Veliyan participates in the tribal literacy programme in Thondarnadu panchayat in Wayanad district. (Photographs: K Shijith)

“When I told her about Aksharalaksham, Karthyayani Amma enthusiastically enrolled for it. Considering her age, we used to go to her house to teach her lessons, essentially basic Malayalam,’’ says literacy prerak Sathi.

The Kerala State Literacy Mission has 2,000 education centres with a literacy prerak each. They are paid Rs 500 for a day’s work. Besides, the 1,750 literacy instructors are paid a monthly honorarium of Rs 2,000.

Of Karthyayani’s six children, a daughter, Ponnamma, 60, has never been to school. “She is not even ready to join the literacy programme. She does not listen to me,’’ says Karthyayani, breaking into a wide, toothless smile.

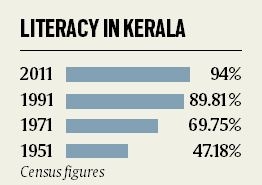

For a state that is among India’s most literate — 93.94 per cent, as per the 2011 Census — the literacy schemes are a way to ensure that no one remains unlettered.

According to UNESCO norms, 90 per cent of the population should be able to read, write for the state to be declared as fully literate. Kerala had met that target way back in 1990, yet, there remain pockets where the literacy numbers dip worryingly — in coastal areas, among migrants and tribals, and among the elderly.

According to P S Sreekala, Director of the Kerala State Literacy Mission, the focus of the Mission’s renewed thrust on literacy is the coastal and tribal areas of the state, where the literacy rates are much below 90 per cent. “Here too, we are focusing on senior citizens, considering the fact that Kerala has among the highest life expectancy rates in the country. More than learning to write and read, the initiative helps the elderly fight loneliness,” she says.

While the 2011 Census had identified 18 lakh illiterate people in the state, the Literacy Mission is conducting a fresh survey to identify the task at hand. A pilot survey held in 2,000 wards of select civic bodies had identified 56,000 unlettered people. The survey will now be extended to 19,000 more wards.

In 2012, after the Kerala State Planning Board found that the coastal areas had among the lowest literacy rates in the state, the Literacy Mission launched Aksharasagaram in six coastal districts in a phased manner.

It also launched Aksharalaksham for those above 16, a literacy project in the tribal belts of Attappadi (Palakkad district) and Wayanad, and a programme for migrant workers, among others.

***

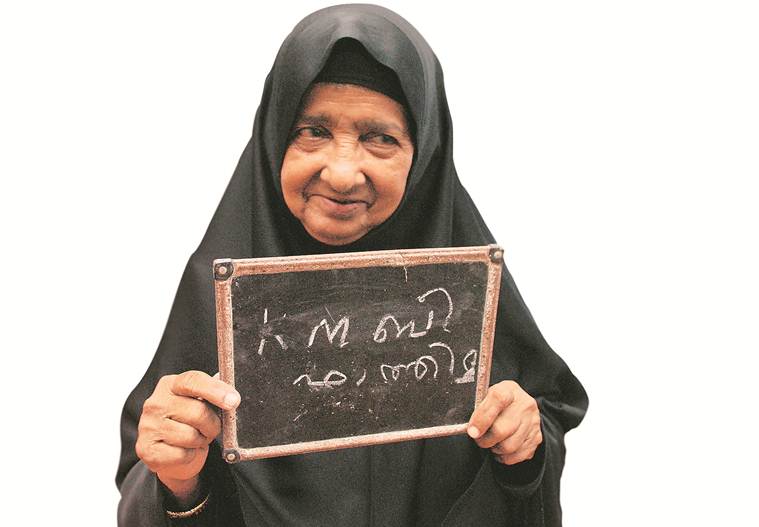

An Aksharasagaram participant, Bifathima K M, 66, of Kizhur in Kasargod. (Photographs: K Shijith)

An Aksharasagaram participant, Bifathima K M, 66, of Kizhur in Kasargod. (Photographs: K Shijith)

Her husband’s death in 2005 filled V Suhara with a deep sense of loneliness. And changed her life. “I decided then that I can’t sit idle at home. My three sons were grown up and married and I had time on my hands,’’ says the 62-year-old.

She is now one of the 330 students of Aksharasagaram, the coastal area literacy programme, at Chemmanad panchayat in Kasargod. At an anganwadi centre in the panchayat, Suhara sits with five other women, all of them bent over the writing slates on their laps as they attempt to write their names.

The first phase of Aksharasagaram, implemented in 13 coastal panchayats of Kasargod, Malappuram and Thiruvananthapuram districts, began in early 2018 with 1,605 candidates. Now in its second phase, the project has identified 5,876 unlettered people in the coastal panchayats of Ernakulam, Kollam and Kozhikode districts. As many as 2,932 of them are now attending literacy classes in the three districts. An overwhelming number of them are women — of 820 people attending classes across Ernakulam district, 727 are women.

In Trikkaripur panchayat of Kasargod, of the 189 who have enrolled for Aksharasagaram, 162 are women. “Most of them are elderly women, many of them widows, who go for NREGA work. Somehow, they are more or less convinced that in future, they would need some kind of basic education to earn benefits from government schemes,” says A Chitra, a literacy prerak at the panchayat.

V Pushpalatha, a literacy instructor in the Chemmanad panchayat, says, “We have several widows attending the literacy programme. For them, these classes are a way to engage with society and a chance to fight loneliness.’’

Explaining the near absence of men at these classes, Kasargod Literacy Mission committee member and Chemmanad panchayat coordinator Rajan K Poinachi says, “The fishermen set off for the seas in the evenings and return only the following morning. So most of them are reluctant to attend classes,’’ he says.

Classes are often held in anganwadis, panchayat buildings and other public spaces, even beaches, but if a person can’t make it to the centre, literacy instructors visit her at home. While basic Malayalam is taught in all these classes, the syllabus is often tailored to meet the requirements of those who enroll. For instance, besides basic literacy, where people are taught to write their names and do their signatures, the migrant programme has modules on spoken Malayalam and the programme for tribals has frequent references to the forest, nature and the tribal way of life.

An Aksharasagaram class being held at a fishing harbour at Varapuzha panchayat in Ernakulam district. (Photographs: K Shijith)

An Aksharasagaram class being held at a fishing harbour at Varapuzha panchayat in Ernakulam district. (Photographs: K Shijith)

Suhara was 14 when she married Abdul Rahman, a fisherman. “I never went to school. As a child, I did all the domestic chores at home and after my marriage, I did everything my husband wanted me to. But after he died, I realised I must do something for myself,’’ she says.

Suhara had other reasons to start learning. Three years ago, she signed up for the MNREGS in the panchayat. Under the job guarantee scheme, members are often asked to sign on the muster roll, forcing many such as Suhara to equip themselves with basic literacy. “At job sites, I developed an interest in learning since there were often discussions about various local and national developments,’’ she says.

Besides, Suhara is now actively involved in Kudumbasree, a poverty alleviation scheme run by the state government.

Suhara says she can now write her name and sign on papers, but “can’t read much”. Suhara’s daughter-in-law Fasila B, however, says there have been other, more visible changes.

“I am amazed at how confident my mother-in-law has become. When she is outside, she greets people, smiles and stops to talk to people. At home, she is now very particular about cleanliness and hygiene. She is signing up for all kinds of health campaign programmes,’’ says Fasila, Suhara’s eldest daughter-in-law.

Fathima K M, 66, goes to the same literacy class as Suhara. Like her, Fathima has never been to school. “When I was a child, the school was very far away from my house and my parents did not let me go. Anyway, I got married at 14 and with that ended any hopes of studying.”

Ten years ago, she lost her husband Mahin, a fisherman in Chemmanad village. Her elder son Abdul Faizal is a fisherman while the younger one, Sameer, is jobless. Fathima’s life started looking up five years ago when she got a sewing machine from Kudumbasree. Later, she enrolled for the MGNREGS. A year ago, she was made an office-bearer of the local Kudumbasree unit in her village panchayat.

“I then had to handle accounts and the savings of members, and make frequent trips to the bank. That really opened up my world. So when the Literacy Mission activists came for the survey, I told them I want to read and write,’’ says Fathima, adding that her son wasn’t happy with her decision.

Experts say government programmes such as Kudumbasree and the MNREGS have played a key role in motivating women to learn.

Kudumbasree Mission Programme manager Giji R S says the poverty alleviation programme, which has 43 lakh women in 2.7 lakh self-help groups, empowers women to make decisions for themselves. “These groups offer a lot of opportunities for women to interact and communicate. During Kudumbasree’s weekly meetings, women discuss local issues, possibly creating an appetite for learning among semi-literates and the unlettered. Besides, a member has to prepare minute-books and handle the funds of the units. Such a situation would prompt those with some initiative to try to learn to read and write,’’ she says.

B Sajith, who worked as joint development commissioner and MNREGS project officer until last month, says, “This interest for learning is one of the hidden impacts of the job guarantee scheme. It is a group activity, where literate, semi-literate and illiterate come together every day. That itself can trigger a desire for learning among those who are illiterate,’’ he says.

Of 15 lakh MNREGS workers in the state, 90 per cent are women.

At 89, Chelli was the oldest among 2,624 people in Attappadi, a tribal belt in Palakkad district, to sit for a literacy exam in August this year.

Sitting in her house at Kuruvangandi colony in Agali panchayat, she says, “When I decided to go for the literacy classes, everyone in our colony scoffed. ‘At this age?’ they all asked me. But I had to study. When I was young, my parents wanted me to attend school, 5 km away from our hamlet, but I never bothered. Now that I have got a chance once again, I decided I must at least learn some alphabets,’’ she explains.

A survey conducted by the Literacy Mission in 2017 revealed that of the 32,956 people of Attappadi, around 2,300 persons had never been to school.

The literacy classes, which began in December last year, are being held in 129 settlements across three panchayats of Agali, Puthur and Sholayur in Attappadi. The Mission has appointed 275 instructors for the programme, 218 of them from the tribal communities of Irula, Muduga and Kurumba.

Ayishumma P A, 47, trying to scribble on a slate as her grandchildren watch, at Chemmanad coastal village in Kasargod. (Photographs: K Shijith)

Ayishumma P A, 47, trying to scribble on a slate as her grandchildren watch, at Chemmanad coastal village in Kasargod. (Photographs: K Shijith)

“Since tribals in Attappadi speak distinct tribal languages, we decided to appoint instructors from their own communities,’’ says Dr Sreekala of the Literacy Mission.

At Kuruvangandi colony, the Mission found 60 unlettered people in 64 households. Instructors have been moving from one house to another, persuading people to come to the community hall, where classes are held every evening.

Literacy prerak P V Neethu says they have also been holding classes at MNREGA sites. “After a hard day’s work, many of the tribals would refuse to come for the evening classes. So we decided to conduct classes during the two-hour lunch break at MNREGA sites. We convinced them that they should be able to write their names and sign on the muster roll to be eligible for their wages,’’ she says.

***

For the first time since S Imran arrived in Kerala around four years ago, the 27-year-old from Murshidabad in West Bengal can read the destination board on buses and bargain with local shopkeepers. “I can read a bit of Malayalam and speak the language better. Earlier, I was never sure if I was being cheated by shopkeepers and always got onto the wrong bus,” says Imran, who works in a plywood factory in Perumbavoor.

Imran was among 503 migrant workers who attended ‘Changathi (friend)’, a pilot programme organised by the Literacy Mission for migrant workers in Perumbavoor, a major migrant hub in Kerala. The literacy drive among migrants began after a survey by the Mission revealed that many of them couldn’t read or write in their own mother tongues.

The project has now expanded to 13 other districts, covering 7,013 migrants. As part of the programme, migrants are given four-month-long literacy lessons in Malayalam. The Mission has also introduced a booklet, ‘Hamari Malayalam’, targetted at helping migrants with the language.

T V Sreejan, project coordinator in Perumbavoor, says the programme had to face resistance from people who employed migrant workers. “We usually hold these classes in factories and other places where we can find migrant workers. Initially, their employers resisted the literacy efforts, probably because they feared that if the migrants learnt Malayalam and became more aware, they would start bargaining for better wages and demand better facilities,’’ he says.

Sreejan says the literacy classes also included sessions on cleanliness and health. “We talk to them about the need to keep their workplaces and quarters tidy. Besides, we also advise them to stay away from drugs. At some of these sessions, we noticed how quickly they learnt to communicate with us and answer our questions in Malayalam,’’ says Sreejan.

The only education Nahal Aslam, 18, has had is in the madrasa he studied in, in Assam for four years. The 18-year-old, who reached Perumbavoor a year ago and works in a plywood factory, says, “For the first time in my life, I am sitting for an exam and have learned to write Malayalam. It has become easier for us to find our way around in the city and bargain in markets.” But he is excited about something else. “I will now start watching Malayalam movies,’’ he smiles.

Literacy instructors Mini, Fazila B, Pushpalatha; prerak Thankamani Cherukara; and literacy programme panchayat coordinator Rajan Cherukara at an anganwadi in Kasargod

Literacy instructors Mini, Fazila B, Pushpalatha; prerak Thankamani Cherukara; and literacy programme panchayat coordinator Rajan Cherukara at an anganwadi in Kasargod

The projects run by Kerala Literacy Mission for 100% literacy

Aksharasagaram: Meant for coastal villages, where illiteracy is higher. In the first phase, the project was implemented in Malappuram, Thiruvananthapuram, Kasargod districts, and 3,568 cleared last year’s exam. Now, the project is on in Kollam, Kozhikode and Ernakulam districts, where 5,876 were found to be illiterate. 3,031 will take the exam this month.

Aksharalaksham: Across all districts. A survey found 47,241 unlettered. Exam was conducted in August this year, with Karthyayini Amma ranking first with 98 out of 100. 42,933 cleared the exam. They can now go in for a Class 4 equivalent programme.

Samanwaya: A continuing education programme for transgenders. As many as 918 showed interest, but only 145 have joined ongoing classes.

Tribal Literacy programme in Wayanad and Attappadi: A survey among 31,831 tribals in Wayanad had found that 9,751 were unlettered. In the first phase, 4,309 passed the literacy exam. For the second phase, 5,342 persons have enrolled. In Attappadi tribal block, the project is to cover 7,922 unlettered people.

Samagra: In 100 tribal colonies across Kerala. 2,179 persons will write the literacy exam on November 25.

Nava Chethana: For 100 Scheduled Caste colonies. 2,266 beneficiaries identified.

Chengathi (friend) : For training migrant workers in basic Malayalam.

Apart from these, classes for prisoners and mental patients.