Abdul Majeed Kakroo at the Polo Ground in Srinagar on Monday. This ground wouldn’t be there if not for his threat to self-immolate back in 2007. (Photo: Mihir Vasavda)

Abdul Majeed Kakroo at the Polo Ground in Srinagar on Monday. This ground wouldn’t be there if not for his threat to self-immolate back in 2007. (Photo: Mihir Vasavda)

Abdul Majeed Kakroo remembers walking home at a furious pace, slamming open the door, picking up a couple of medals and walking straight out, without mentioning a word to his startled wife. It was a pleasant spring day in 2007. And Kakroo was enraged.

Word had gotten out that the then chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Ghulam Nabi Azad, wanted to convert the TRC Ground into a tulip garden. Kakroo didn’t mind the tulips, but was sure the move would’ve brought an end to football in Srinagar. “A few decades ago, there were around 25-26 grounds in Srinagar. But one by one, all those grounds were encroached upon and now they’ve constructed buildings on them. TRC was one of the few grounds left, there was no way I could’ve seen a tulip garden developed there,” he says.

So Kakroo, the first player from Kashmir to captain India, took it upon himself to protect the stadium. “I had two South Asian Games gold medals, and I said I will burn myself outside the secretariat,” he says, sounding agitated even as he recalls the episode. A few other notable sporting names from Kashmir joined him in the protest, and Azad eventually had to relent.

On Tuesday, the first-ever I-League match in the Valley, between Real Kashmir and Churchill Brothers, will be played on that very ground. Kakroo might have stopped playing more than 25 years ago. But he continues to stamp his authority on the state’s footballing landscape even today.

“Majeed bhai hai toh Kashmir mein football hai,” says Mohammad Yousuf, the coach of a local team. Around here, Kakroo is more than just a footballer. Everyone has a Majeed bhai story. But Majeed bhai is quite a storyteller himself.

***

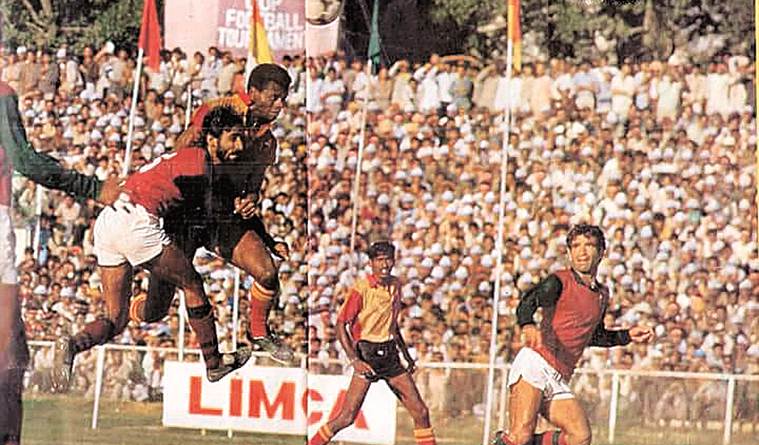

A newspaper cutting, provided by Kakroo, shows him jostling for the ball in the Calcutta derby against East Bengal.

A newspaper cutting, provided by Kakroo, shows him jostling for the ball in the Calcutta derby against East Bengal.

Kakroo played football in more than a dozen Indian cities, in front of thousands of fans. But it’s the games he played post midnight at Lal Chowk, the Srinagar city centre, which he remembers most vividly. This is back in the 1970s, when around 25 men used to converge on a tiny square between the Palladium Cinema and the Clock Tower. “That was the only spot in the entire city which had streetlights. So after the 12 o’clock show ended, our show used to begin,” he says.

The skills he honed as a street footballer took him to places he could never imagine. In the second half of the ’70s — 1977 to be exact — the Road Transport Corporation (RTC) team offered Kakroo his first professional contract — with a salary of Rs 180 per month. RTC was one of several government units big on football. And for a son of a vegetable vendor who’d started playing the sport using crumpled paper as a ball, this was a princely sum. But it was just the beginning.

Teams from Kashmir, in the late 70s, were known for the individual brilliance of a few players. But collectively, they rarely posed a threat. “At the Durand Cup, we were known as the savere-waali-gaadi-se-chale-jaane-waali team (a team that’ll take the morning train back) since we’d travel all the way to Delhi, lose the first match and return,” he laughs.

That reputation would change in 1980. Kakroo’s team RTC, playing its first Durand Cup, reached the quarterfinals, where they lost to JCT. “Pehli dafa tehelka macha dia (We created a stir in our first appearance). I ended up scoring 18 goals in that edition,” he says.

Kakroo had drawn the attention of the national team scouts and GMH Basha, the then India coach, summoned him for a national camp in Bangalore. Kakroo packed a few belongings and took a bus from Srinagar to Jammu first. He then embarked on another long bus journey to Delhi, from where he boarded the train to Bangalore. It took five days for him to reach the southern city.

But the long journey proved futile. Kakroo wasn’t selected for the national team. “Left paanv banaa aur phir aa (improve your left foot and then come back to me),” the coach told me.

***

Real Kashmir footballers train at the TRC Turf Ground in Srinagar Sunday. They face Churchill Brothers Tuesday. (Photo: Mihir Vasavda)

Real Kashmir footballers train at the TRC Turf Ground in Srinagar Sunday. They face Churchill Brothers Tuesday. (Photo: Mihir Vasavda)

At first, Kakroo didn’t quite understand what Basha meant. There weren’t any qualified coaches in Kashmir who could decode those words for him, either. But he realised the flaw in his game. “So during training, I started to wear a stocking over my right football shoe and then put a sharp stone inside it. If the ball touched it, my toes would pain unbearably. That way, I forced myself to control and kick the ball using only my left foot,” Kakroo says. “I did that for several months and left paanv banaya.”

At the Rovers Cup the following year, Kakroo says he scored 26 goals. The clamour to include him in the national team grew, but the team management chose Biswajit Bhattacharya ahead of him. Kakroo is dismissive of the Kolkata striker. “Woh hero jaisa dikhta tha. So they took him, and I returned to Srinagar.”

But when he scored back-to-back hat-tricks in the Santosh Trophy in Thrissur that year, they couldn’t ignore him anymore. For the next eight years, Kakroo remained a constant in the Indian team and even captained the side. He went on to become one of the highest-paid footballers in the country after Mohun Bagan offered him Rs 60,000 per month.

ALSO READ

“My first salary was Rs 180.” he smiles. “Subrata Bhattacharya (former Bagan defender) told club officials one day, bokac***da, isko Kashmir se laaya aur 60,000 deta hai aur mujhe 45,000. He even accused me of ‘buying’ one section of the crowd to cheer me during matches! For more than one year in Kolkata, I didn’t have to pay for a cup of tea. I even saw all movies for free!”

Those were heady days for Kakroo and, in turn, for football in Kashmir. But all that would change in 1989.

***

Majeed Yousuf, who played for the state youth teams and is now a football administrator, remembers the early days of the Kashmir conflict in a different way than others. “I was returning from a tournament in Sonepat and on the way back, when we entered Srinagar, the streets were completely deserted. I could only see men in uniform,” he says.

Later that evening, he heard that Kakroo was detained by the forces. “And I thought, if they can do that to him, then it could happen to anyone,” Yousuf says.

Kakroo recalls the incident. “I was walking to the training ground and two vans zoomed in. One stopped in front, another behind me. They thought they had arrested some big terrorist. Eventually, they checked my ID card and let me go.”

Another time, they barged into his house in the middle of the day during a crackdown and, along with a few other men from the neighbourhood, herded him to a nearby ground where he was made to sit on his knees while the forces searched his house. “All they could find was some footballs, jerseys and medals. It kept on happening. It hurt. I’d played in every corner of the country and in 25 countries. It was humiliating.”

Kakroo cut short his playing career and returned to Srinagar to be with his family during those volatile times. From 1989 to 1996, football came to a complete standstill. But still, there was hope. Whenever curfew was lifted, even if it was for an hour, the youth invested that time in playing football, Yousuf says. As life limped back to a semblance of normalcy, football once again became a priority. And Kakroo was in the forefront of it. He began coaching local teams, where he spotted Mehrajuddin Wadoo — who went on to play several matches for the national team.

“Still, we lost an entire generation of players. This was one of the major reasons why sport collapsed in this region. If you played at TRC or Polo Ground, there was a risk that you could be arrested. These venues were out of bound for us,” he says.

Kakroo had seen how football had died when the TRC Ground was snatched away from them. So when Azad chose that as the location for a tulip garden, one can understand why he was enraged. “I had to protest, and I wasn’t alone. The entire football fraternity was with me,” he says.

The garden, named after Indira Gandhi, was then made on an open space near Dal Lake. It’s the biggest of its kind in Asia and was opened for visitors last year. On Tuesday, a refurbished TRC Ground will witness a landmark moment of its own. And to the relief of many here, especially Kakroo, it’ll be about football.