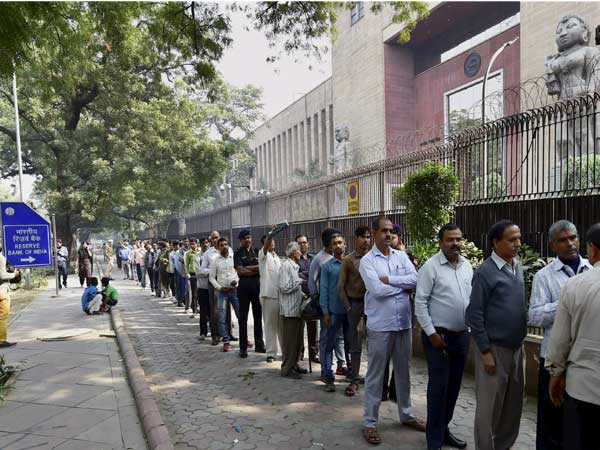

Two years ago, on November 8, 2016 prime minister Narendra Modi announced demonetisation to arrest black money in the economy. The withdrawal of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes influenced all sections in all the corners of the economy and had a significant impact on the banking sector.

While demonetisation failed in its desired objective of curbing black money and slowed economic growth, it benefited banks immensely. Banks could accept deposits without any cost of promotion and drastically increased the liquidity position of banks. Unaccounted money in the form of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 flowed into banks and the sizes of deposits increased as it induced a slosh of liquidity.

Credit growth

Credit growth revived to double digits in 2017-18 from a historic low in the previous year and lending rates for borrowers fell for some sectors. Demonetisation also increased the number of account holders in banks besides increasing digital transactions. As the demonetisation impulse is behind, many trends have reversed again. Liquidity is scarce again although for entirely different reasons. Indian markets that enjoyed a benign local liquidity period over the last three years are likely to see tighter liquidity for the foreseeable future. Default by IL&FS (AAA rated non-bank) and tighter bond market spreads are causing market jitters.

Tax evaders managed to legalise their ill-gotten gains – at least this is what the numbers tell as 99.3 per cent of demonetised notes have returned the system, according to the Annual Report of 2017-18 released by the central bank in August this year. The numbers were released after almost two years since demonetisation.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its Annual Report for 2017-18 said that the exercise of counting the demonetised notes is over. Of the Rs 15.41 lakh crore worth Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes in circulation on November 8, 2016, when the note ban was announced, notes worth Rs 15.31 lakh crore (99.3 per cent) have been returned. The “humungous task of processing and verification of specified bank notes (SBNs) was successfully achieved,” it said. This meant just Rs 10,720 crore of the junked currency did not return to the banking system.

Economic growth

GDP growth fell during the demonetisation and the Goods and Services Tax (GST) implementation period of 2016-17, undershooting potential growth of 7.1 per cent. The start of 2018 marked a period of overshooting, thanks to a low base and inventory re-stocking. According to most economists, growth is expected to remain elevated at 7.8 per cent in 1H18 and gradually return to trend by end-2018.

“Monetary transmission from the policy rate to banks’ deposit and lending rates improved during 2017-18, facilitated by the demonetisation-induced slosh of liquidity, but it remained uneven across sectors and bank groups. In particular, the pace of reduction in lending rates for fresh rupee loans was impeded by asset quality concerns and risk-averse behaviour in lending activity.”

Cash is king again

According to RBI’s report, the value of digital transactions in FY18 went up to Rs 1,373 lakh crore from Rs 1,121 lakh crore in FY17 and Rs 920 lakh-crore in FY16. While this implies that people are more frequently transacting digitally, it paints a different picture when read with the numbers on currency in circulation. The currency in circulation went up to Rs 18.29 lakh crore in FY18 from Rs 13.35 lakh-crore in FY17 and Rs 16.63 lakh-crore in FY16. As on September 14, 2018 the currency in circulation was Rs 19.5 lakh crore.

Says Praveen Dhabhai, chief operating officer of Payworld, “Digital transactions have largely grown in urban areas but not in rural areas. Post demonetisation since cash was scarce, merchants agreed to pay the merchant discount rate and digital transaction rose. But in rural areas, retailers/merchants do not want to pay the merchant discount rate and so digital transactions have not picked up in rural areas.”

Deposit growth

Aggregate deposits accounted for around 93 per cent of reverse money following their sharp increase in Q3 of 2016-17 due to substitution of currency with public by deposits in the post-demonetisation phase. With the phase-out of restrictions on cash withdrawals and the gradual pick-up in currency demand, deposit growth started decelerating and reached its lowest level of 2.6 per cent on December 8, 2017. Over the rest of the year, deposit growth increased steadily, but at 5.8 per cent on March 31, 2018 it was sizably lower than 11.1 per cent a year ago. Both demand deposits and time deposits shared this moderation as the interest rate on deposits eased, with banks transmitting the cumulative reduction of 200 bps in the policy rate by the Reserve Bank almost fully to term deposit rates.

This resulted in the returns on deposits turning less attractive relative to competing financial instruments, particularly mutual funds. This disintermediation impacted deposit behaviour significantly. The combination of surplus liquidity conditions in the wake of demonetisation and lower offtake of credit consequent upon slower economic activity also worked to mute the expansion of deposits in H1 said the RBI report. In the current year so far (October 12, 2018), on YTD basis, deposits grew by 3.2 per cent or Rs 3,59,900 crore (0.6 pre cent or Rs 68,100 crore) and advances by 4.3 per cent or Rs 3,67,700 crore (0.3 per cent or Rs 22,500 crore). On a year-on-year basis, aggregate deposits grew by 8.9 per cent or Rs 9,60,200 crore (last year 9.2 per cent or Rs 9,15,000 crore) and advances grew by 14.4 per cent or Rs 11,29,100 crore (7.2 per cent or Rs 5,30,200 crore). This is the highest growth in almost four years, as 14.5 per cent growth was seen in January 2014.

Credit growth

The growth in scheduled commercial banks credit started decelerating from November 2016 and reached an all-time low of 3.7 per cent on March 3, 2017. Although credit growth recovered in the subsequent fortnights, it trailed well below its trajectory in the previous year through April-October 2017.

Besides the aftershock of demonetisation, weak demand for new bank financing and deleveraging by banks struggling with provisions for mounting loan delinquency also took their toll. Non-banks replaced bank credit as sources of funding for the commercial sector during this phase. From November 10, 2017, credit growth picked up as the quickening of economic activity spurred a hesitant recovery and levels of non-performing assets started plateauing albeit at elevated levels.

By December 22, 2017, credit growth touched double digit – 10.3 per cent for the first time since September 30, 2016. As on March 31, 2018, credit growth stood at 10.0 per cent significantly higher than 4.5 per cent last year. Schedule commercial banks credit growth stood at 12.8 per cent as on June 22, 2018 (5.6 per cent during the corresponding fortnight in the previous year). Even as the system is grappling with a liquidity shortfall, credit growth during April to September this year has jumped by Rs 3 lakh crore, the highest in 4 years, of which Rs 2 lakh crores was in September only.

Dividend payment

The demonetisation exercise had hit the central bank’s dividend payout to the government at Rs 30,659 crore for 2016-17, a fall of 53.45 per cent compared to the previous year. The RBI had paid a dividend of Rs 65,876 crore for 2015-16. For 2014-15, the RBI dividend was Rs 65,896 crore. Cost associated with printing of new notes, destruction of old notes post demonetisation and reverse repo operations to suck out surplus liquidity were the main reasons for such a deep cut in RBI’s dividend payout to the centre.

However, in August this year, it paid Rs 50,000 crore as dividend to government in line with the Union budget provisions, helping the centre stick to its fiscal roadmap. The Reserve Bank, which follows July-June financial year, has paid about 63 per cent higher dividend than the previous year (2016-17). The RBI made a dividend payout of Rs 30,659 crore for the fiscal ended June 2017. In addition, earlier in March, the RBI paid interim dividend of Rs 10,000 crore at the insistence of the government to support fiscal position.