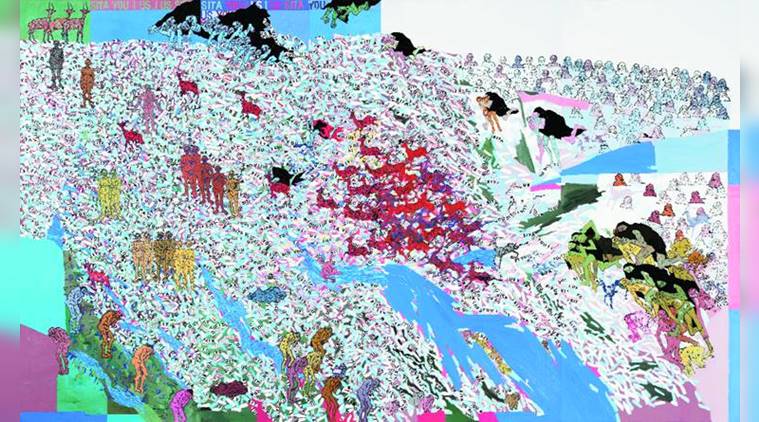

The turnaround: In this 2014 oil on canvas, Searching Sita, Through the Papers, Delhi-based artist Arpita Singh reflects on the trauma of being dislocated from one’s comfort zone. “The very fact that Sita was forcibly removed from her own location is a great crime,” says Singh, who admires Sita for her strength.

The turnaround: In this 2014 oil on canvas, Searching Sita, Through the Papers, Delhi-based artist Arpita Singh reflects on the trauma of being dislocated from one’s comfort zone. “The very fact that Sita was forcibly removed from her own location is a great crime,” says Singh, who admires Sita for her strength.

My mother’s name is Sati. Since I learnt that name before “Sita”, for a large part of my childhood I suspected that people were mispronouncing my mother’s name when they mentioned Ram’s wife and not my father’s. By the time I discovered Sita — on Doordarshan, like many of my generation — I had learnt about anagrams. Anagrams, to a child as obsessed with words as I was, had created a relation between the two names by then — just as there was a god in dog and vice versa, there was a Sati in Sita and Sita in Sati. Both were difficult to see — the dog inside god, and Sita in Sati. Every Sunday morning, therefore, between the broadcast of Ramanand Sagar’s television serial and a lunch of mangsho-bhaat, I inspected my mother and all her actions with a sideward glance.

I was yet to become aware of my number-obsessed nature, and, relationally, a naïve and native structuralist tendency, but as she moved around, I tried to decode everything she touched and did into anagrams. Dal I saw as “lad”, sag as “gas”. When she put the mutton into a pressure cooker, I was sure that it was a goat we would be eating and not a dog: “no mutt”. Among the many things adulthood took away from me, it was this silly obsession with anagrams, this desire to see something else in a thing or people that was partially hidden, a bit like Sita, inside the earth, the forest, her complete self invisible to her husband.

On pavements and railway platforms, and oftentimes even in shops selling stationery in India, there were charts illustrating — and advertising — an “Ideal Boy” or a “Good Girl”. It is a readymade code of goodness, one whose axis is obedience — listening to one’s parents, the nation, god. The boy or the girl in these posters did not have a name. And yet, because of our socio-religious conditioning, we knew who they were — the go(o)d boy is Ram, the good girl Sita.

There’s an invisible pressure on us to be them. The first step in this direction is, of course, through naming. (It’s the same reason parents — or grandparents — name their children Happy, so that they become Happy.) How — or why — is it, then, that we know more men with the name Ram than we do women with the name Sita? Is it that becoming Sita is more difficult — and less desirable and less painful — than becoming Ram? Or, is it tautology that women are already Sita, and that naming — the word — doesn’t have to abet it? As a teenager more interested in words than in people, I remember noticing the name of the politician Sitaram Kesri, and thinking how unequal the rules of naming were that a man could claim the names of both Sita and Ram but a woman couldn’t (Sita is called Janaki, after Janak, her father, and also Rama, after her husband; the men do not take her name, of course). What did that mean to my anagrammed world? I still cringe in embarrassment at the memory of the anagram I created out of the name Sitaram: I am Star. There’s a moral about the male ego there, I can see now.

With time, my interest in the anagrammatic trails of Sita’s name — and their possible interpretations — began to weaken. But I should add that I did find a man inside Sita as I had found a woman in Sitaram — one anagram of Sita is Asit, a man’s name, also used for Krishna. It means the dark one. Once again, I found a story in that discovery.

I heard the sound of her name in the most unexpected places. When a son was born to a cousin, the nanny would always say “ta” to my cousin’s “Si Si Si”, a sound used to invoke or trigger a child’s urination. I thought it a tic until my cousin explained it to me — the woman was completing the sound of the name — Si-Ta, Si-Ta. There’s a story — and, of course, a moral — in there, too.

What I’ve been trying to say, through the recollection of these anagrams and found sounds about her name, is the fact of her hiddenness, and a consequent ascription of incompleteness in our imagination. She, by virtue of her birth, born of the earth as it were, was meant to be half-hidden, like the plough is visible only through the marks it leaves. It must have been that feeling — of her invisibility, of her dependence on the world for meaning, that made me name Sita as Kobita in Missing, my first novel, where I was aiming to explore the Ramayana as a “diminished epic” by placing the characters in a small town in sub-Himalayan Bengal, and where India’s Northeast had become the new Lanka. Unlike “Sitaram”, for instance, where the man lays claim to the male and female conceptual categories, Ram and Sita, Kobita meaning “poetry” has the word kobi, poet (a male poet; a female poet, sometimes called a “poetess”, is a relatively new phenomenon, perhaps only as old as the Industrial Revolution), inside it. For Sita is a poetic trope — of fertility, of blessings of the soil, of agriculture, as her birth in a ploughed field tells us.

Living in a time of warfare as we do today, an unceasing warfare against Sita and Kobita, the stories of the epic acquire new and powerful connotations. The loss of the poetic (Kobita) has been simultaneous with the loss of the earth (Sita). In a world where the environment has begun to protest against our atrocities on it at last, turning from ally to enemy, the torture of Sita, she of the earth, her exile, her kidnapping, her banishment, her test by fire, all of these read like alarming prognostications now — the earth’s revenge. The Age of Ramayana has treated the earth like Sita for far too long — with indifference, unconcern and disregard, while also glorifying this treatment. As we hear the voices of Sitas emerge from below the earth around us at last, it might be a moment of shift in history — the Age of Sitayana might have just begun.