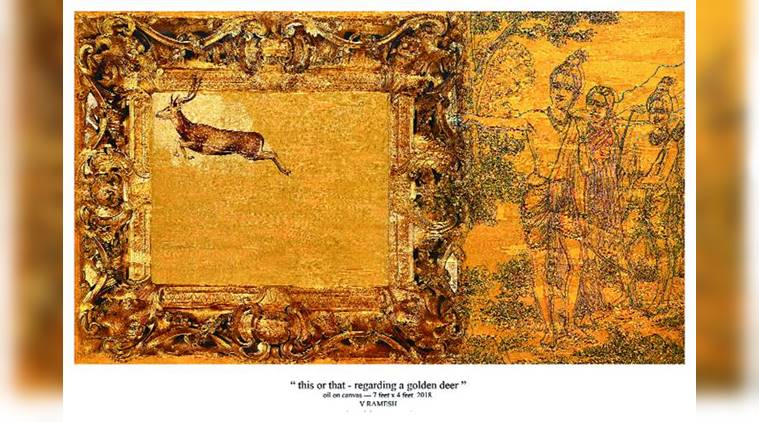

The golden glow: Visakhapatnam-based artist V Ramesh’s oil-on-canvas, This or That: Regarding a Golden Deer (2018). (Courtesy: Anant Art Gallery, Delhi)

The golden glow: Visakhapatnam-based artist V Ramesh’s oil-on-canvas, This or That: Regarding a Golden Deer (2018). (Courtesy: Anant Art Gallery, Delhi)

Diwali approaches with its clear skies, a crisp coolness in the air. The sounds and smells of festivity surround us, comforting as a favourite, familiar shawl. Temple bells. Lines of light set outside doors and along rooftops, be they flickering diyas or multicoloured electric bulbs. Fragrant incense. New clothes. Fun-filled gatherings of family and friends. The acrid, beloved — and now controversial — smell of fireworks.

Diwali approaches, the season of divine beings. It is the time when we pray to goddesses — Lakshmi or Kali — to destroy evil inside and outside us and grant us prosperity. We celebrate gods — Ram or Krishna — and rejoice in their victory over the forces of darkness.

But as Diwali approaches this year, one being rises above the others in my mind, human and divine at the same time. Sita.

This in itself isn’t surprising. Diwali, in many states, celebrates the triumphant return of Ram and Sita to Ayodhya after their long exile to reign as king and queen. I have often imagined Sita being welcomed back by the women of the city, their arms around her, their cries joyful . What a tender reunion that would have been!

But that’s not the reason I’m thinking of her today.

Sita has haunted me ever since I was a girl and first heard the fascinating, multifaceted story of the Ramayana from my grandfather.

As a young woman, I wasn’t particularly fond of Sita. Perhaps, this was because I was instructed so often by my elders to be like her. I was told she was devoted and long-suffering, that she put up with all the troubles heaped upon her by life. She didn’t rebel, didn’t fight back. She got along, meekly, with everyone around her, and willingly sacrificed her happiness for their sake.

I pressed my lips together in silent rebellion. I had no desire to be a woman like that. May you have a husband like Ram, the elders said in parting.

I didn’t answer. I knew from experience that speaking my mind on such issues only got me into trouble. But inside me a rebellious voice cried: Why? Didn’t Ram cause Sita the greatest grief of her life?

In spite of my teenage dismissal of her, I couldn’t forget Sita. There was something mysterious and slippery about her which I couldn’t quite grasp but which fascinated me. What was it exactly?

As a college student, I read and re-read the Bengali Ramayana by Krittibas that occupied a place of pride on the bookshelf in my parents’ house, hoping to find an answer. And, as I turned the pages, I thought I heard her whisper, Tell my story again. Tell it in a different way. Tell it your way. For the great and timeless stories of a culture must be re-created over and over so that they may remain relevant to the times.

For years, I resisted. Even after I completed a novel in the voice of Draupadi, The Palace of Illusions (2008), and it seemed to find favour among readers, I was still reluctant.

The subject of Sita was too great, too grand, too important. Draupadi was a woman, after all. But wasn’t Sita divine? Did I even know how to write about such a being?

The voice inside my head wouldn’t go away, though. Year after year, it insisted, “Tell my story. I may be divine, but I’m a woman, too. I have much in common with the women of India. Indeed, with the women of the world. Try to discover what it is.”

It said, “Here is a hint. Tell of my courage. Because it took courage for me to stand up against everyone, to insist that I must accompany my beloved Ram to the forest. It took courage to remain strong and not give in to Ravan during all those dark months I spent as a captive in his kingdom. After I was rescued by Ram and then rejected by him, it took courage to call for a fire, and to walk into its blaze rather than put up with my husband’s stinging, undeserved insults. It took courage to forgive him and return to Ayodhya as his queen. It took courage when he sent me away into the forest, pregnant with his babies, to give birth and raise them the best I could on my own. And it took the greatest courage to say no when Ram asked me to return as his beloved queen — but only if I underwent an unjust trial, once again, by fire”.

“But I’m afraid,” I would say. “Do you think I wasn’t?” she would reply. “Over and over, I was afraid. It’s natural to be afraid. Courage is often preceded by fear. But we can’t stop there. We have to work through it. We have to keep the heart strong. We can’t give in.”

This Diwali, I’m thinking of Sita more than ever before, because I’ve finally completed the task she set me.

Dear Sita, I have now written your story. I don’t know if I’ve done you justice. I hope I have. In writing it, I have realised that it is at once a timeless story and a story for our time. Your life and courage, pain and strength, your loving heart, your stubbornness as you pushed your way through darkness into light, speak clearly to the women of today. The ones who are finally coming forward and saying, enough of compromise. The ones who are saying, even as they are terrified of the fallout, #MeToo, I will not remain silent in the face of the wrongs that have been done to me. And the ones who are standing staunchly beside them in sisterhood.

I hope your life will inspire them. I hope when they bless their daughters, they will say, “Be like Sita”, and realise what it truly means.