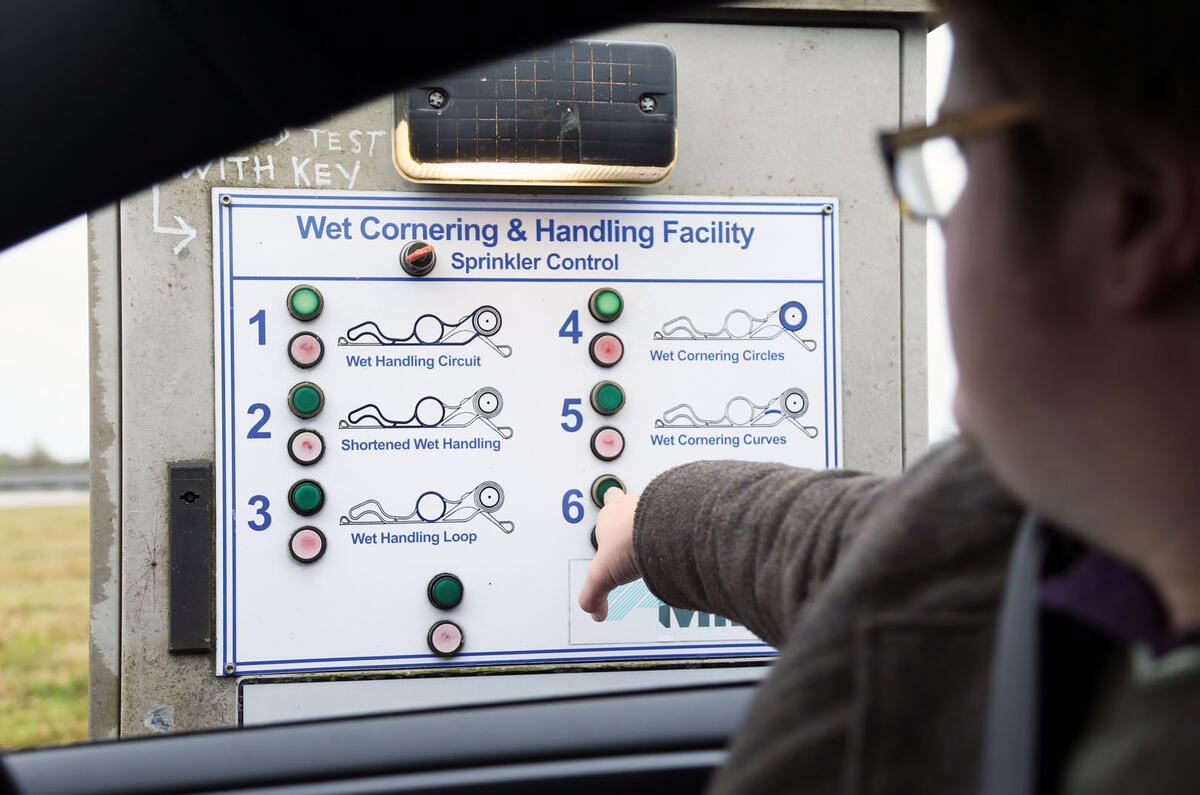

It has done so out of necessity, of course, as the cars this magazine has intended to assess have changed – and our expectations of them have changed likewise. The road tester’s toolkit has also changed quite a bit, in ways we’ll get on to – and which, in the process of researching this article, have made me very grateful indeed (a nod to the editor for that).

If we had presented this week’s road test on the McLaren Senna in the same format as the first of two tests in our 13 April 1928 issue, on the Austin Seven Gordon England Sunshine Saloon and the Wolseley 12-32hp, here’s what you’d have got. Among 14 paragraphs published in total on the Austin, only four concerned driving impressions: the rest were mostly descriptions of the car’s layout, body, roof and interior, and of the practicalities pertinent to the refilling of engine oil and adjustment of the handbrake. Exciting, eh?

In the ‘data for the driver’ panel of empirical test results, meanwhile (the sort that would come to define the road tester’s job), the only numbers that appeared were of maximum speed and maximum acceleration in each of the car’s three gears (47mph flat out in top), its average fuel consumption (42.4mpg) and its stopping distance from 25mph 9a full 48 feet in this case).

That was, of course, because the road test of the day had bigger fish to fry. This was a time when getting to your destination at all could be stymied by your car’s mechanical frailty, its inability to climb or even to start in the first place, or the meekness of its brakes. And so we learned that the little Austin “would hold 21mph in second on a gradient of 1 in 10”, and that “in first gear, it held plenty in hand on a gradient of 1 in 4, even on a slippery and rutty surface”.

I reckon a McLaren Senna would “hold rather more in hand” on a steep hill. For the record, it’d probably climb a 1 in 4 gradient like an Exocet missile leaving a silo. Still, I can’t be sure, ’cos that’s no longer a part of the test.

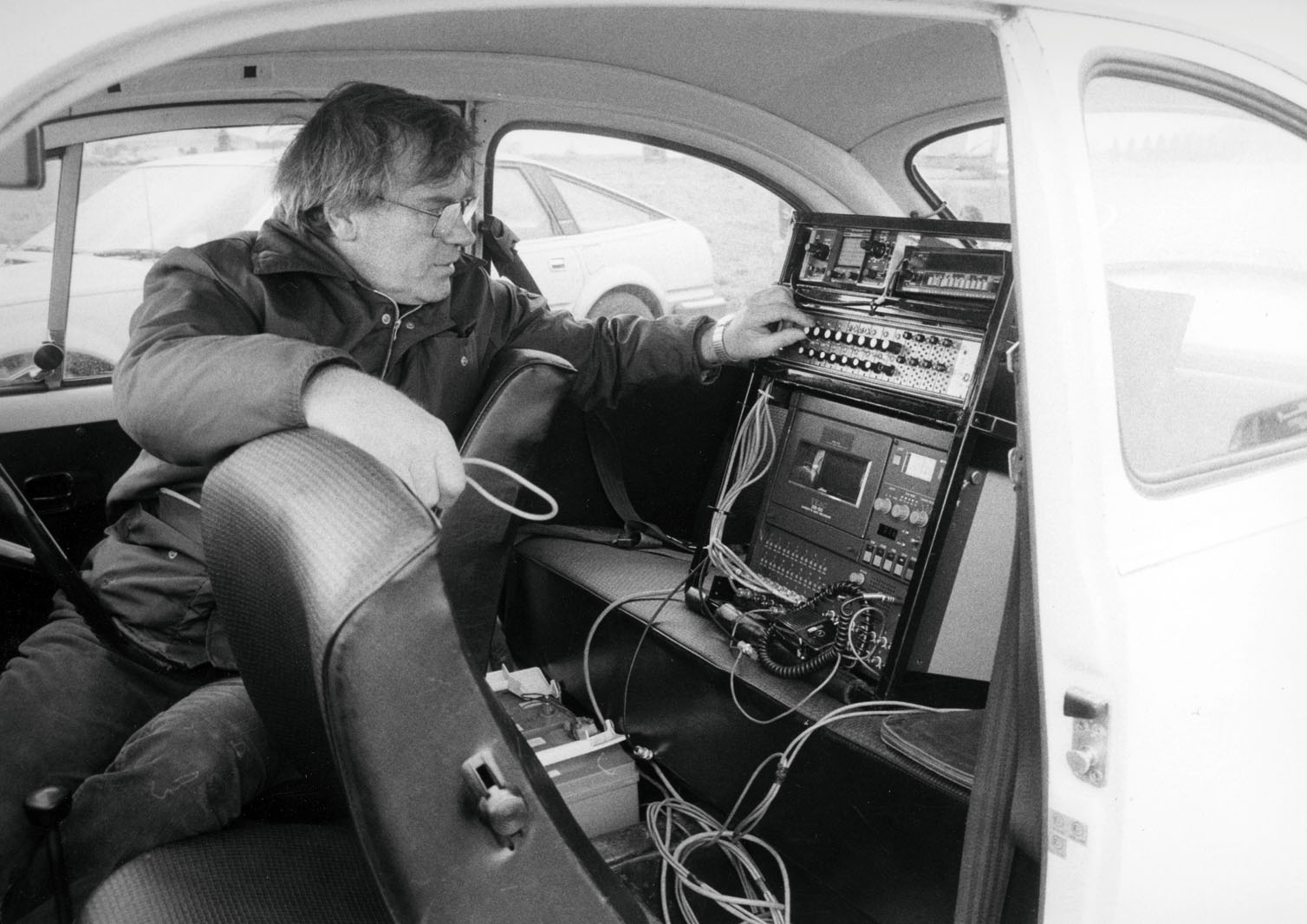

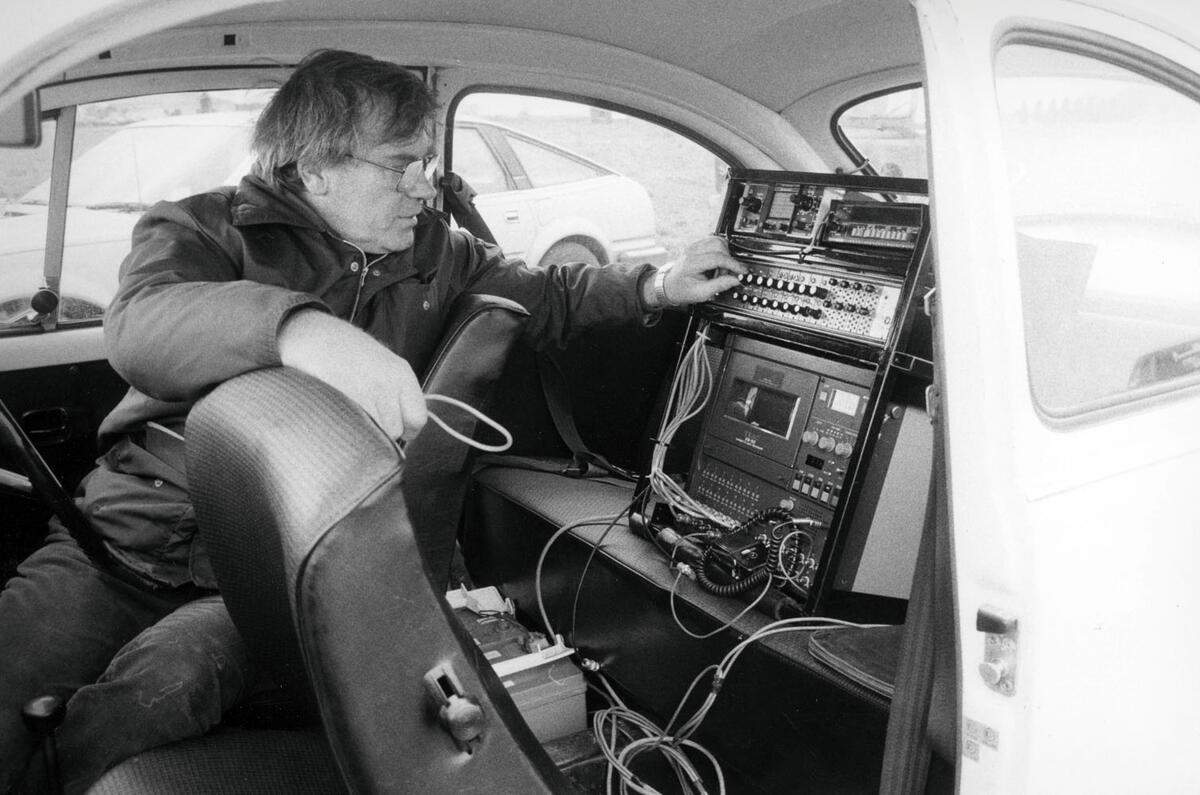

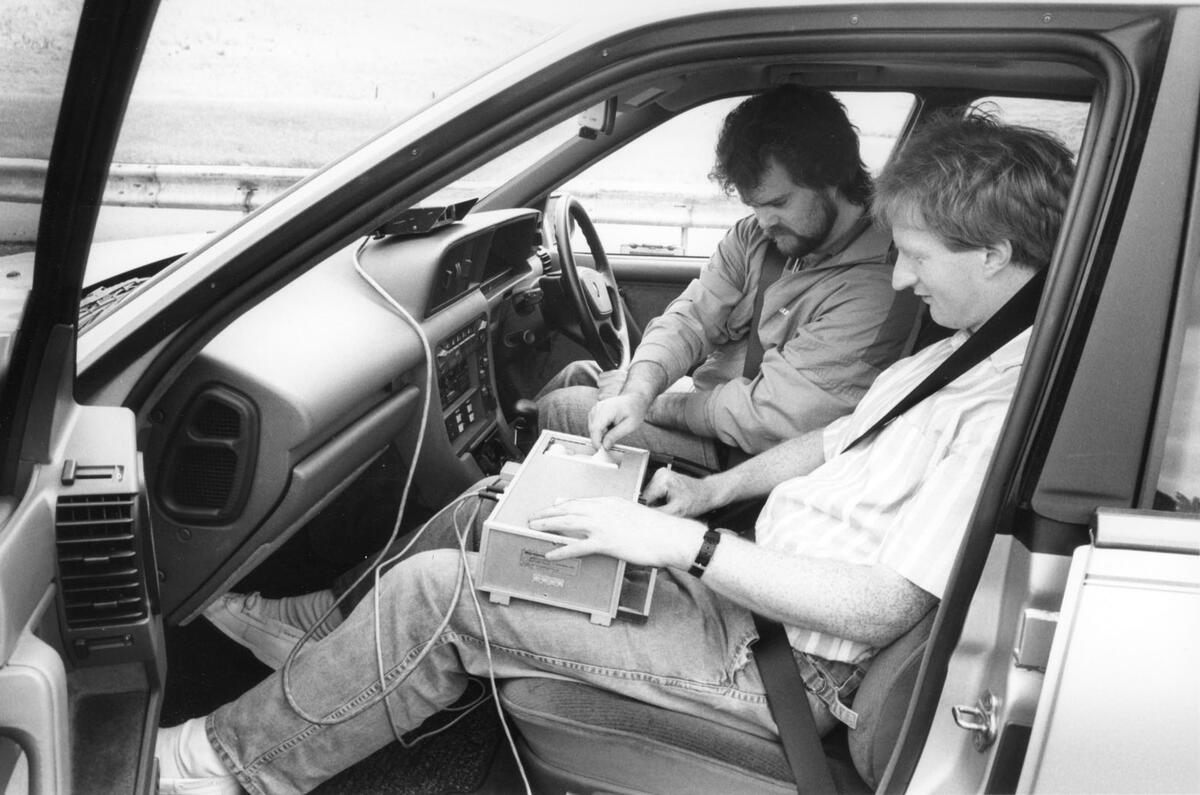

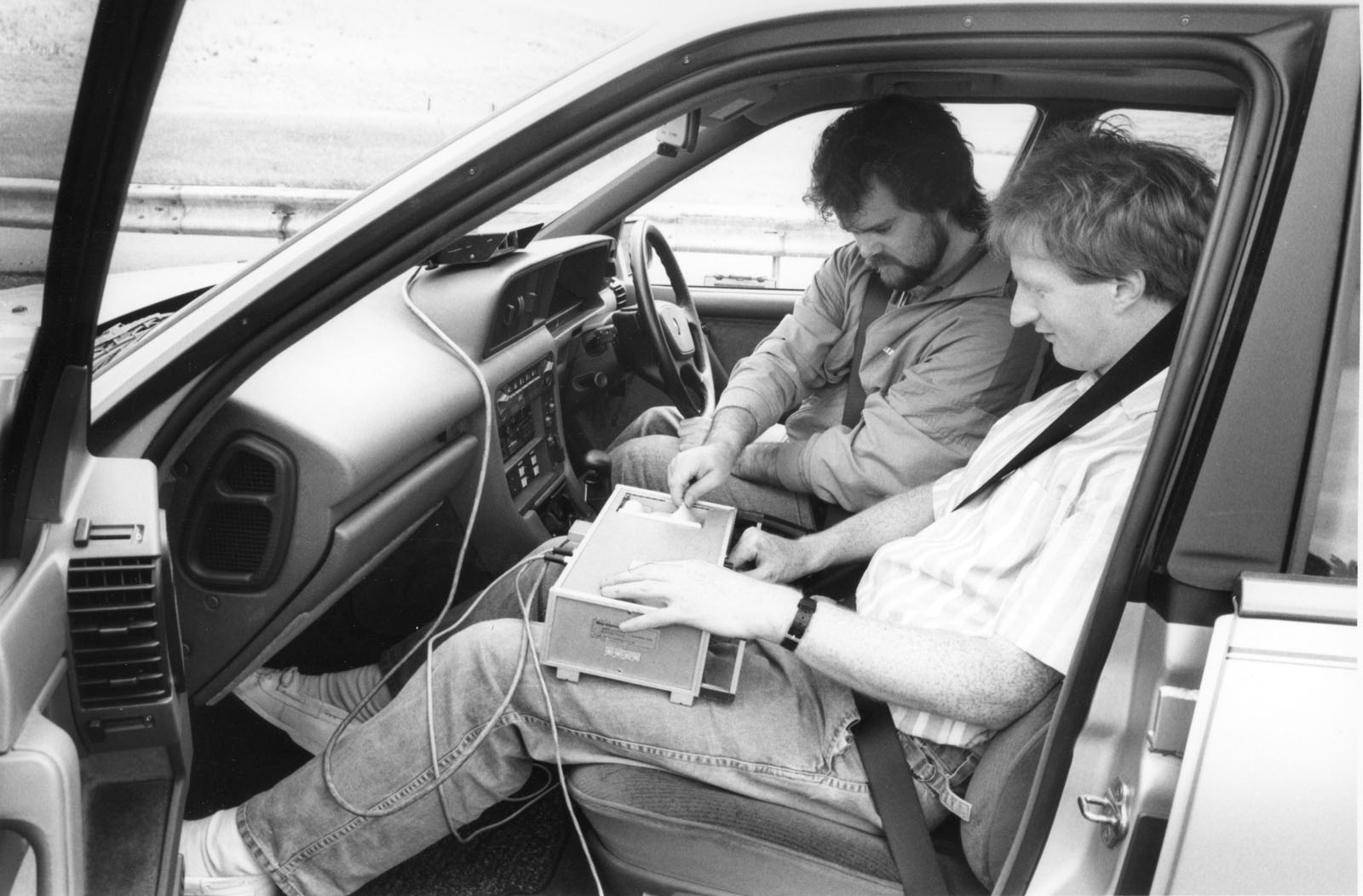

And what of equipment? Autocar’s road test pioneers needed nothing more than a stopwatch, a measuring wheel (for recording turning circle and stopping distance) and a pencil to log the data they needed for their work. They also worked in pairs out of necessity, rather than for reasons of consistency as we do today.

In-gear speed maxima were timed over a measured distance and the car’s instruments duly calibrated. And although the number of stopwatches a co-driver might simultaneously operate rapidly grew in order that several accelerative increments could be timed at once (a set of four watches wouldn’t have been unknown in pre-war testing), it was decades before other testing apparatus started to have an impact on the road testing process.

Add your comment