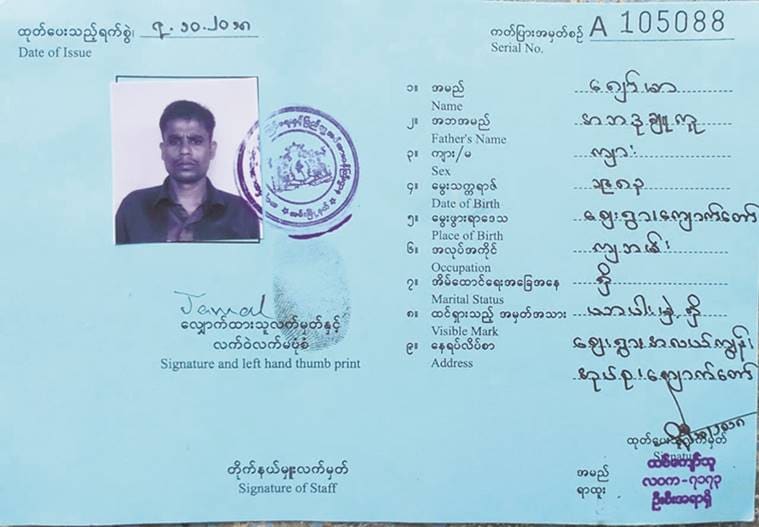

National Verification Card, issued Oct 7, to one of the returnees.

National Verification Card, issued Oct 7, to one of the returnees.

The seven Rohingya men repatriated by India to Myanmar on October 4 are back at their homes in North Rakhine’s Kyauktaw area. They were escorted through a four-day journey from Moreh to Kyauktaw by Myanmar immigration officials, and were handcuffed for part of the way.

“We were brought here in a car. Four of us are from Bazar Fara, and are now with our families. Three were from Foidafara, and they were taken there,” said Mohammed Jamal, one of the seven men, in halting Urdu. The Indian Express was able to trace the men through the Rohingya refugee network in Bangladesh. UNHCR sources also confirmed that the men had reached their homes in Rakhine.

The four back home in Bazar Fara, near Kyauktaw town, are Mohammed Shabir Ahmed, Mohammed Yunus, Mohammed Salam and Mohammed Jamal. Kyauktaw is in Mrauk-U district of north Rakhine. Mohammed Maqbool Khan, Mohammed Rohimuddin, and another person called Mohammed Jamal have reached their homes in Foidafara, in Pauktaw village tract. Jamal said they went by road from Moreh to Mandalay, and further onwards to Rakhine province, located in the north-west of Myanmar. He said they were treated “bahut achcha (very good)” by the immigration officials. “They bought us food along the way, there was no problem. We came in a government car,” he said.

He also said they were handcuffed for one day during the travel, between Mandalay and Magwe, on way to Rakhine state. Another returnee, Mohammed Yunus, said they were handcuffed as soon as they reached Mandalay, where they were taken to an immigration office, “kept in a closed room, and made to sign some papers”.

The maulvi of the Bazar Fara Masjid, Mohammed Nasir, said the men arrived accompanied by immigration officials at 8 am on October 8. “They arrived safely and all have been reunited with their families,” he said. Since their arrival, police officials in plainclothes have been to visit their homes.

Jamal said all the men have been given National Verification Cards (NVCs). The date of issue on the NVCs is October 7, 2018. The NVC is not a citizenship card, but is said to be a step toward enabling the holder to apply for citizenship under the 1982 Citizenship Act. Myanmar does not accept Rohingya as its citizens. Rohingya refugees camping in Bangladesh have, in fact, refused to accept the NVC, on the ground that it is another ploy by the Myanmar government to delay giving citizenship.

The men said they had left Kyauktaw in April 2012, months before the two rounds of communal clashes later that year between Rohingya Muslim and Rakhine Buddhists claimed many lives and led to thousands leaving their homes. “We went with a man called Robert. Woh Mizoram ka dalaal hai (He is an agent from Mizoram in India). He was supposed to get us jobs in the Middle East,” Jamal said.

He also claimed that they had no idea they had crossed over into India when they were caught. The journey involved a bus trip and a lot of walking through forests. “Robert also got caught, but he was given bail and we don’t know where he is now,” Jamal said. “Robert was supposed to find us jobs, but we did not work a single day,” he added, while denying paying any money to Robert.

Jamal said they wanted to leave as there are no jobs for Rohingya in Myanmar, and they could not leave their neighbourhoods for cities in Rakhine or elsewhere to look for opportunities. “I cannot leave my basti even to go to Kyauktaw town,” said Jamal. Maulvi Nasir said that before 2012, Rohingya had some freedom of movement, and could travel to even Yangon with permission to pursue paperwork and documentation at government offices. “But since 2012, there are strict rules that we cannot leave our villages. To describe our situation briefly, we are nazarband (confined) in our bastis. Isey ek open jail samajhiye (Think of it as an open jail). Even to go from one Muslim basti to another, we are permitted only to use the river route, we are not allowed to go by road as Buddhist villages are en route,” Nasir said.

With few jobs available among Muslim bastis, Nasir added, “Everyone wants to leave. There is nothing here. Most Muslims who have fled Kyauktaw preferred to go to Malaysia by illegal routes. Dalaals take them. If it’s a dalaal, money must be changing hands. They don’t do anything for free. Some have also gone to Bangladesh.”