The present church is ultra-modern compared to the old Portuguese one.

The present church is ultra-modern compared to the old Portuguese one.

Dadar, Mumbai’s first planned suburb, is in popular imagination a place where culture and politics meet. When the Salvacao Portuguese Church, also called Our Lady of Salvation Church, was renovated in 1977, it was the first-of-its-kind makeover the city had seen. Gone were the steeples, the choir loft, the ascending roof and ornate facade, to be replaced by conical domes connecting the sanctuary (altar), the nave (central aisle), the baptistery (baptismal font), and the oratory (shrine). Charles Correa, by then, was already a Padma Vibhushan awardee, and had held the position of chief architect for Navi Mumbai.

The church was originally built by Portuguese Franciscans in the late 1500s and went through three renovations as it expanded. Correa was commissioned the revamp in 1974. In an essay in his book A Place in the Shade, Correa writes of how architecture unites us, despite differences in religious beliefs. How the axis mundi (the column of the universe connecting the earth to the sky) is fundamental to the architectonic symbolism in universal places of worship. This “open to sky” motif appears in almost every Correa project. In this church, he attempts that with the conical flues, while the interconnected walkways and central courtyard become as much a congregational space as the interiors.

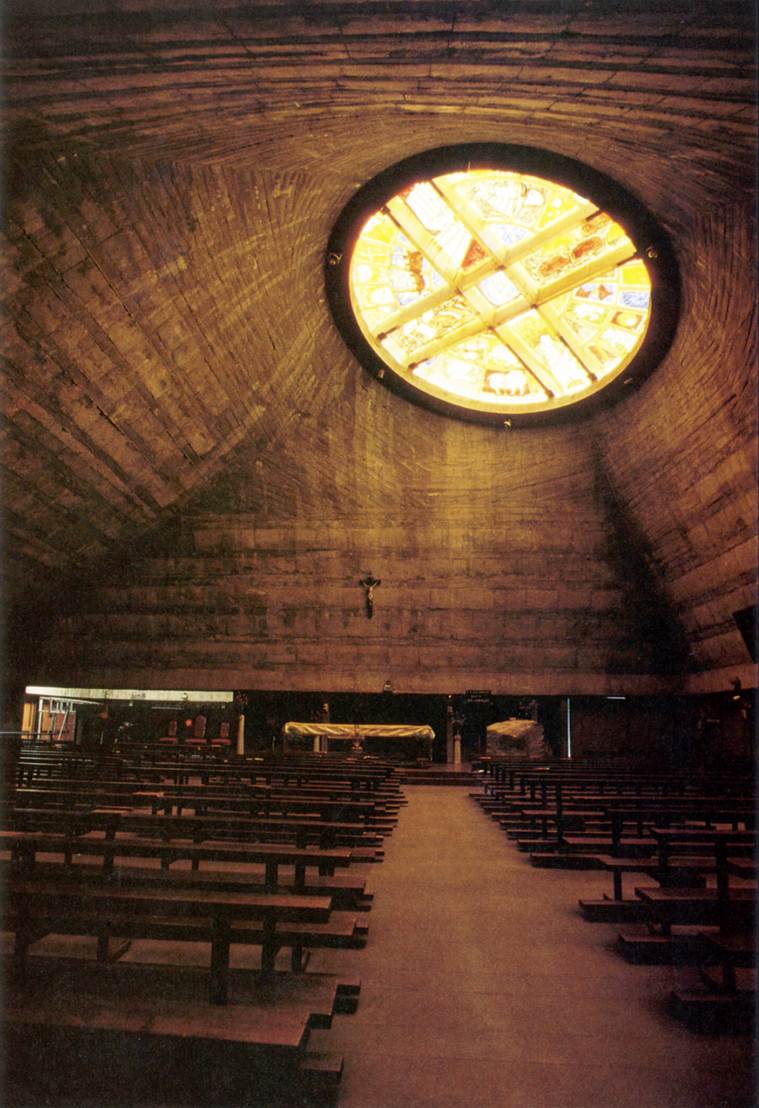

Correa’s other tradition-defying act was to invite MF Husain to do a fresco on glass for the central dome. It was his idea of externalising the “social aspect of religion”. Husain divided the glass into several segments for a stained-glass effect and painted the story of the five loaves and two fish, and the death and resurrection of Christ. On sunny days, it’s ethereal to see the light stream through the painting.

God’s grace: The fresco on glass painted by MF Husain.

God’s grace: The fresco on glass painted by MF Husain.

“I experienced what a space is for the first time with this building,” says Smita Dalvi, a professor at the Pillai College of Architecture, Navi Mumbai, as she recalls her days as a student architect. “A church is traditionally about the architecture of the interior spaces, and here Correa moves from the inward space to the outward form.”

By turning walls into generous doors all around, not only does Correa manage light and ventilation but also ensures participation of the people in the liturgical rites on busy days such as Christmas and Good Friday. There’s no escaping the heat, though, say parishioners.

“The present church is ultra-modern compared to the old Portuguese one with its baroque architecture. It is unlike any other church in Mumbai, with its inverted cones and without steeples. Since there are no high roofs, we face acoustic issues. There are places within the church where you sometimes can’t understand the priest or the choir. We try and work our way around it,” says 85-year-old Sydney Mendoza, who was the choir conductor of the church from 1965 to 2000.

While many are undecided if they like or dislike of the building, it’s to be said that Correa’s ambition in this project gave many students of the time hope in the many possibilities that architecture contained.