Several women have come forward to name their predators and recount in detail the nature of harassment they have had to suffer. (Illustration: C R Sasikumar)

Several women have come forward to name their predators and recount in detail the nature of harassment they have had to suffer. (Illustration: C R Sasikumar)

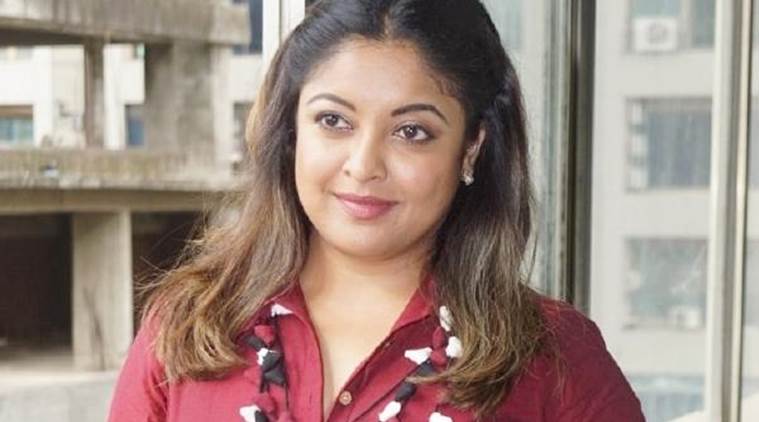

For the first few days after Tanushree Dutta spoke up about the abuse she faced at the hands of actor Nana Patekar, she feared a repeat of the stifling silence of 2008, when she first accused the actor of harassment.

“Soon after I had spoken, there was denial from my harassers, a smear campaign against me had started, I was slapped with two legal notices and the media seemed to treat the story of my sexual harassment as a sensational piece of news. I then thought that just as in 2008, the commotion I had created would die down and this fight would end in a lonely battle that will once again drive me back into my hole,” says Dutta.

Looking back at the events that have unfolded over the last three weeks, the 34-year-old is glad she stood her ground. What began with Dutta’s allegations of sexual harassment against Patekar on the sets of the film, Horn OK Pleassss, has stirred up a storm in the film industry. Several women have since come forward to name their predators and recount in detail the nature of harassment they have had to suffer. It has led to what is being called India’s #MeToo movement, snaring several big names in its wake.

These include Alok Nath, who has been accused by TV producer Vinta Nanda of rape, harassment and intimidation. There have been accusations against filmmaker Vikas Bahl. Around the same time, Phantom Films, the indie film production house Bahl owned with Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane and Madhu Mantena has been closed. With several women accusing filmmaker Sajid Khan of harassment, he has had to step down from helming the fourth installment of the comic franchise, Housefull. Aamir Khan and wife Kiran Rao have chosen to distance themselves from Jolly LLB maker Subhash Kapoor, who was to direct a film under their banner.

Dutta is relieved that the conversation is no more being helmed by her alone. “In 2008, when I openly accused Nana Patekar, I stood out like a sore thumb because there was a culture of silence prevalent in the industry. But this time, it has started a dialogue and the numbers have made it a movement. As a result, the shame and stigma attached to being a survivor is also diminishing, thereby empowering other women to speak up,” she points out.

In fresh FIR, Tanushree Dutta claims her 2008 complaint was not registered properly

In fresh FIR, Tanushree Dutta claims her 2008 complaint was not registered properly

An industry of silence

Has much changed in the industry over the last decade, then?

Dutta believes it helps that the new crop of women actors are more vocal and aware of social issues and speak up in support of each other. “At least things like equal pay and casting couch are a part of public discourse today. Back then, speaking up amounted to slander.”

Former film journalist Shobhaa De agrees. Looking back at the years when she was active, De recounts that unlike today, “there was zero sisterhood — at least publicly”. “The level of insecurity was high and the opportunities to crack the big roles comparatively low. The male actors called the shots as they do even today. Women stars were in no position to stand up to the system. Or defend themselves.”

De’s 1991 novel Starry Nights more than hints at the patriarchal, sexist and predatory nature of the industry. “Very few women were spared… and that has not changed. The only women who escaped were those belonging to powerful Bollywood families. Or those who came with rich patrons and godfathers to ‘protect’ them. This meant just one thing — without that protection, you were up for grabs… fair game. Some of our top actresses started life under pretty sordid circumstances and worked their way up,” adds De.

Most young girls entering the film industry were therefore aware that their dreams could come at a high cost. A young indie filmmaker, who started out as a child actor, recounts an incident where she was groped by the house help of the producer she was working with.

“I was all of 13 and travelling with my mother in the producer’s car to a shooting location. I was asleep when they stopped to freshen up. My mom had stepped out for a few minutes when I woke up to this man groping me. I was horrified. My mother later told the producer, who not only dismissed the incident but also told us that we should expect such behaviour if we want to be a part of the film industry,” she says on condition of anonymity.

TV and theatre actor Susmita Mukerjee, best remembered for her role as Kitty in the show Karamchand, points out that such instances were in no way uncommon. “The producer of a South Indian film once propositioned me. I cried all day and eventually quit the project. Another senior director told me very casually that I should be open to ‘compromises’ if I want to be an actor,” she says.

Mukherjee believes it helped that she wasn’t looking to be a star. “I was happy with television and theatre, choosing to do bit roles in films, so it was easier for me to escape exploitation,” adds the actor who played Alok Nath’s wife in Tara.

Women would thus have to devise their own ways to stay away from unwelcome advances.

Dutta, who has accused director Vivek Agnihotri of inappropriate behaviour on the sets of the 2005 film, Chocolate: Deep Dark Secrets, says that incident prompted her to hire a massive entourage. “I realised that I cannot battle them alone. So I hired a staff who would go with me everywhere. I became unapproachable. Anyone who needed to reach me would have to go through a series of interactions with my staff first. In fact, it took the makers of Horn OK Pleassss three months to get a meeting with me,” she recounts.

This, De says, was the reason many women actors brought along their mothers or even grandmothers to shoots. Actresses also hired male secretaries who doubled as bodyguards. Despite these measures, midnight knocks, many say, were routine.

In the early 2000s, the industry began to undergo a change. The television industry witnessed a boom and studios entered the fray, streamlining the functioning of the chaotic, unorganised film industry. The content too underwent a change and the focus shifted to more urban stories in both cinema and television.

Looking back, Vinta Nanda remembers that as a time when the industry opened up to women, offering them roles beyond that on the screen.

However, while the number of women working in the industry increased, so did instances of harassment. “We adapted to the West in terms of functioning but we didn’t borrow their ideas. So, say, casting directors became a norm but they also became the facilitators of the casting couch. And while there were more women helming projects, working as assistant directors or editing, the male point of view had not evolved to view them as equals. In their heads, women’s roles were limited to secretaries. So often, women technicians would be treated that way,” Nanda points out.

This resistance to change has long reflected in Bollywood’s content. For a long time, mainstream stories remained centred on the hero while the women leads were seen as mere showpieces or glamorous accessories. It wasn’t until a decade ago that women began sharing the centre stage with men. Ironically, several filmmakers who are credited with having championed this change with their ‘woke’ ideas and cinema, have found themselves at the centre of the #MeToo controversy, most prominently Queen director Vikas Bahl.

Thirty-two-year-old Shiuli Das, who has worked as an assistant director on several films, including Ek Thi Daayan produced by Vishal Bhardwaj and Umesh Shukla’s All Izz Well, points out that the industry set-up remains gender insensitive.

“Women technicians have to use unhygienic washrooms on film sets and the sanitation system is not conducive for women during their period. It’s difficult to explain to male colleagues that one needs to take a break between a shot to change a sanitary napkin because it is viewed as an excuse,” she says.

Das adds that often the behaviour of male colleagues can be both patriarchal and patronising. “They throw technical questions at you in order to throw you off, especially if you are senior to them. It doesn’t matter if the woman they are dealing with is from a film school or not,” she says.

This attempt to establish the power equation is often coupled with predatory behaviour at wrap-up parties or during post-shoot get-togethers. “I was once sharing a room with an art assistant on an outdoor shoot. On the evening of a party, I returned to my room early while she sat back with the crew for a couple of drinks. But when she returned half an hour later, she was in a noticeably bad state. Upon insisting, she revealed that the director sitting next to her had slipped his hand under her dress,” recounts Das.

“Because he was known to be a respectable man, this girl first went through self-doubt, wondering if she was mistaken. But then was sure when in the evening following that party, she would receive text messages from him, inviting her to his room for a drink,” Das adds.

Such blatant harassment is often a product of the sexist work environment. Make-up artiste Serina Tixeira points out that she is often asked by male colleagues to “hire good-looking hairdressers”. There have been instances where executive producers on reality shows have called for photographs of those applying for internships so they can “choose carefully”.

A hint of change

Over the last few years, production houses have, however, begun to take measures to counter such instances. Farhan Akhtar’s Excel Entertainment, Yash Raj Films, Anushka Sharma’s Clean Slate Films and Ekta Kapoor’s Balaji have special cells to address sexual harassment cases.

Excel’s legal head Pooja Sharma says their Internal Committee is in line with provisions of The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and redressal) Act, 2013 and covers freelancers working for the production house. “After-parties also count as workplaces hence incidents taking place at such events are also taken cognizance of. We also provide complete confidentiality to the complainant, as per the provisions of the Act,” says Sharma.

Also on the rise are awareness programmes on sexual harassment. For instance, Netflix India’s training programmes on what may constitute sexual harassment covers everyone from the lead actors to the spot boys. Their docket on the subject points out that catcalls, sexual jokes, narrating sexual fantasies, apart from unwelcome physical conduct, count as sexual harassment.

While the grievance redressal mechanism exists in the industry, women are not always sure whether this will bring them justice.

“Whether justice will be done often depends on who the predator is,” explains a woman executive producer who does not wish to be named. “Imagine a scenario where an assistant director lodges a harassment complaint against an actor during an outdoor shoot, where every minute counts because the expenses keep mounting with every delay. Since the onus is on the producers to address such complaints, they choose to hush up or dismiss the complainant instead of incurring financial losses,” says Das.

Going back to the incident she narrated earlier, she says, “The girl couldn’t muster the courage to tell her art director, fearing that she will be viewed as a nuisance who needs chaperoning. She also gave up the opportunity of taking on a bigger role in the film because that would have needed her to interact with the director.”

The examples in the public domain are not encouraging either. “Aishwarya Rai was the one who lost work after speaking up against an abusive Salman Khan, not the other way round. Or, let’s go back to the fact that Tanushree Dutta’s FIR and complaint in 2008 to Cine & TV Artists’ Association (CINTAA) went unheeded. Eventually, she was the one who quit the industry and left India,” says Das.

However, the emergence of the #MeToo movement and the resultant support from the industry has left women optimistic. “Accepting that sexual harassment exists is the first step, and this is the first time the industry has officially acknowledged it,” points out Nanda. She hopes that the special committees that CINTAA, Producers Guild of India and Federation of Western India Cine Employees (FWICE) intend to form, will stay unbiased in nature when power centres are challenged.

Dutta, however, is aware that the fight is far from over. And while she recognises that she has been the catalyst for the movement, the former beauty queen chooses to wear this crown lightly. “I am merely an instrument. Any real change needs tangible impact. While I am optimistic, it is important that every single case that has emerged be closely inspected. And unless we don’t boycott these predators, making them suffer for their actions, it will not act as a real deterrent, reducing the industry’s support to mere lip service.”

***

(From right to left) Vikas Bahl, Alok Nath and Kailash Kher are some of the men accused of sexual harassment.

(From right to left) Vikas Bahl, Alok Nath and Kailash Kher are some of the men accused of sexual harassment.

Nana Patekar: Tanushree Dutta first levelled allegations against Patekar in 2008, after she walked out of the shoot for a song for the film Horn OK Pleassss after the actor made her uncomfortable. An FIR and a complaint with a film association were filed but both were eventually dismissed. She reiterated the experience in an interview last month, which led to India’s #MeToo movement. Film associations have since kicked into action. Dutta, too, has filed a fresh FIR in the case. Patekar has in return sent her a legal notice. Patekar has also stepped away from Housefull 4, which he was a part of.

Vikas Bahl: An investigation by a web platform revealed that an employee of Phantom Film, co-owned by Bahl, underwent sexual assault, followed by harassment over an extended period of time. Bahl’s partners Anurag Kashyap and Vikramidtya Motwane ignored her complaint. The production house has since been dissolved.

Alok Nath: TV writer-producer Vinta Nanda has accused the actor of rape and assault on multiple occasions and eventual sabotaging of her career. She has filed a complaint with a film body, which has sent Nath a show cause notice. Nath has also registered a defamation case against Nanda.

Sajid Khan: Recently, actor Saloni Chopra published an account of harassment against Khan, recounting the time she worked as his assistant in 2011. Journalist Karishma Upadhyay has also shared her account of Khan allegedly indulging in dirty talks and exposing himself when she had gone to his sister’s house to interview him. Khan has since stepped down from his role as a director on Housefull 4.

Kailash Kher: Several allegations against the singer have emerged, including one by his colleague Sona Mohapatra. Kher issued a statement apologising “if he has been misconstrued”.

Rajat Kapoor: Several women, including a journalist, came forward alleging sexual misconduct on part of Kapoor. The actor apologised via social media.

Subhash Ghai: An anonymous person has accused Ghai of drugging and raping her while she was employed with him. The filmmaker issued a statement saying he is “deeply pained” to have been “gripped in this movement”.

Varun Grover: An anonymous account by a girl, who claims to be Grover’s batchmate in college, has claimed he misbehaved with her on pretext of narrating a scene for a play. Grover has issued a statement denying the claim and sought an investigation.

Subhash Kapoor: Actor Geetika Tyagi was allegedly assaulted by the Jolly LLB director in 2012. She even published a video where Kapoor can be heard confessing to the act. While an FIR was filed by Tyagi in 2014, the director was only recently dropped from the Gulshan Kumar biopic Mogul. Ekta Kapoor also dropped him from a web series he was directing for her production house.