Limba Ram is the chief coach at the Jagatpura archery range in Jaipur. (Rohit Jain Paras)

Limba Ram is the chief coach at the Jagatpura archery range in Jaipur. (Rohit Jain Paras)

Limba Ram wears a genuine smile as he walks up a flight of stairs at the entrance of the archery range at Jagatpura on the outskirts of Jaipur. For most of the past week, Limba, the superstar-archer who captured the imagination of the nation in his heyday as he journeyed from a tribal village to a near-tryst with an Olympic medal, has been bed-ridden. His right-side — from face to feet — were limp and paralysed and he couldn’t talk. If he tried to stand up, he would deflate like a balloon which had lost air.

Limba is in high spirits. He is tentative as he walks down the steps. There is no sign of the neuro-degenerative disease, which has afflicted him. Till he sits down in his office room and starts talking. The speech is slurred at times and he can be incoherent. Yet like a radio frequency that suddenly springs back to life he becomes audible again, even a little too loud when he insists that ‘this is a good day’ for him.

“If you had come a few days earlier, you perhaps would have not got a word out of me,” Limba says. He mock-strangulates himself for a second or two to demonstrate how difficult it can be for him to utter two words when his voice box is jammed. “Today I am able to sit and will talk to you for hours. Hopefully, I won’t bore you,” he says laughing. For a man diagnosed with an illness, which cannot be cured but only controlled at best, Limba retains a sense of humour.

The alarm bells went off in March during a routine training session. The voice of the state academy’s chief coach suddenly turned garbled and he lost his balance. Limba brushed it aside. His wife Merian Jenny would have none of it. The 46-year-old was admitted to the city’s Sawai Man Singh Hospital and after a series of tests, the diagnosis pointed towards multiple system atrophy. He was discharged a month later and put on medication. Limba has ‘good days’ and ‘bad days’ as he puts it.

“What is most frustrating is that I have lost strength in my right shoulder. So I cannot pull the bow string. Basically, I cannot use the bow and my grip is weak. I can’t propel an arrow towards the target. My hand-eye coordination is poor. When an archer cannot use his bow and arrow, he becomes half the person he was,” Limba says with a touch of resignation.

Nowadays Limba does not venture out of the academy premises as a precaution except when accompanied by someone when he visits a doctor or a physiotherapist. “He has fallen when trying to walk up the steps to the archery range. He can suddenly lose his bearings,” his wife Jenny says. The couple have been allotted make-shift quarters within the archery range.

This evening he is itching to watch the trainees practice and takes the effort to climb a flight of stairs. “I don’t like anyone holding me. If I fall, I fall. Limba Ram is not so weak that a fall will affect him,” he says adamant.

On seeing Limba, the budding archers make a beeline towards him. One by one they hurry to touch the feet of the revered coach, even as he directs them to quickly get back to their routine. There is genuine warmth and excitement among the trainees on seeing the legendary archer because these days he is not as regular as he used to be at the range. “These kids used to run away on seeing me,” Limba says jokingly, adding “that is how hard I used to make them train. Nowadays they get off lightly.”

He spends half an hour going around the range, watching the trainees practice and correcting their technique before deciding to call it a day.

Limba says he has been ill before. Six years ago when he was India’s chief coach at the London Olympics he was sick. After a bout of vomiting which lasted two days, he was bed-ridden he says even as the Games were in progress. In 1996 too, Limba recalls that his body was sapped of all energy but back then nobody could put a finger on what caused the extreme fatigue. This year is the first time he consulted a team of doctors. That’s when he was diagnosed with the neuro degenerative disease.

***

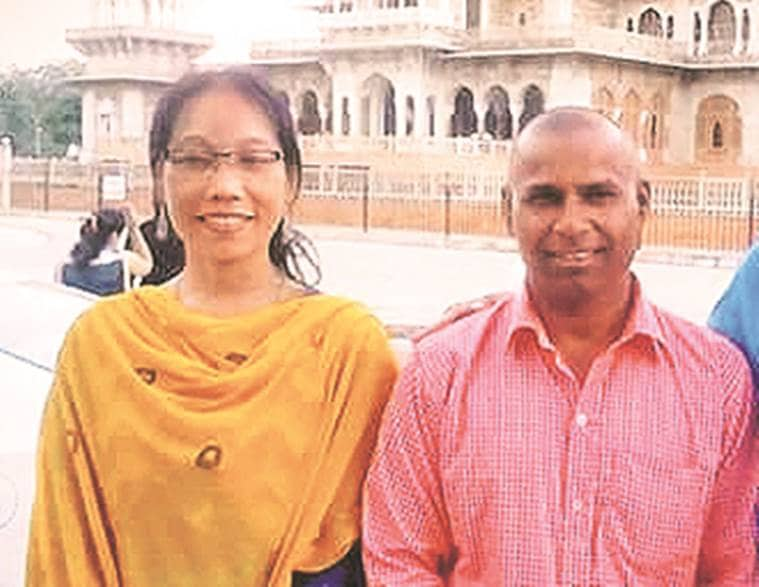

Limba ram with wife Merian Jenny.

Limba ram with wife Merian Jenny.

Limba was named Arjun Ram at birth and was one of five children. He was renamed Limba after the local deity, when he recovered from chronic fatigue when he was still a toddler.

According to the last census data (2011), Saradeet village, Limba’s birthplace, has a population of 1,386, a majority of them who fall under the schedule tribe category. The village, with 267 households, is in Jhadol tehsil in Udaipur district and has a literacy rate of below 50 percent. The village was electrified and a pakka road was laid at the height of Limba’s fame when he missed a bronze at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics by a single point.

Though the doctors concluded he had a neuro-degenerative disease in April this year, the archer insists he has been living with symptoms since 2015.

In June that year, Limba and Jenny, who is from Assam, got married. They had first met at a tribal sports mahotsav in Pratapgarh. Jenny was a programme co-ordinator for a child health project. When they first met, Jenny had no clue who Limba was. They hit it off, over subsequent meetings and phone conversations.

Cultural differences or age – Jenny is 10 years younger than Limba – mattered little back then because they found a strong bond in their common faith. In the early 2000s Limba turned to Christianity after he met a pastor whose prayers ‘healed him’.

Being from two ends of India and living together can present its own set of challenges, Jenny says. “We are very different people. Even adjusting to each other’s food choices can be difficult. Limba sir likes rotis and if I eat rotis I get indigestion. So I cook both rice and roti. And the sabzis, let us not even get into that,” she adds.

The couple have made peace with their diverse dietary preferences but prickly issues crop up whenever they travel to Saradeet. And they are graver.

“All the women are in a ghoonghat in Limba sir’s village. I am not used to covering my head and face. To avoid displeasing people I followed the tradition. I am from a different part of India and I stand out when I go to the village. I try not to offend anyone. Yet on a few occasions I didn’t wear the ghoonghat and it was frowned upon. It can be a little difficult when there is a cultural difference,” Jenny admits.

Limba’s current predicament tugs at her heart strings. “He is a simple man and is good at heart. At the end of the day, I have to accept that this is a difficult period and he will come out of it. The story of how he rose from a village to become one of the best archers in the world is inspirational. Hopefully, this is another battle he will win.”

***

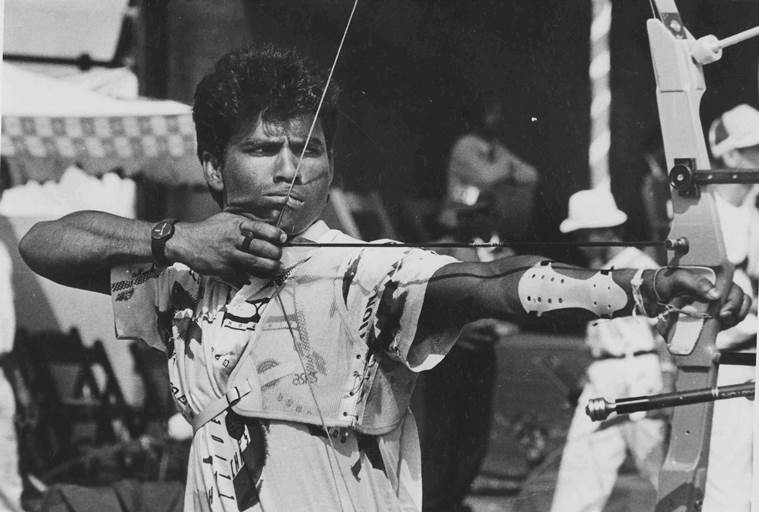

A young Limba Ram in his heyday. (Express Archives)

A young Limba Ram in his heyday. (Express Archives)

In the winter of 1987, 15-year-old Limba arrived in Delhi, after being selected under a Special Area Games Programme of the Sports Authority of India. His only belongings were a blanket, a khaki shirt and a pair of khaki pants. “Back then khaki- coloured clothes was the fashion,” he recalls.

The family plunged into poverty when the cows they owned, died mysteriously. Limba, to make ends meet, worked as a house help and also ploughed the field. “There were thorns in my feet because I used to be barefoot. But I could not afford a pair of slippers.”

When he found time and energy he used to participate in the only ‘sport’ in Saradeet village – taking aim at birds using the desi bow and arrow. He was good at it.

An uncle informed him of the archery selection trials at Makradeo, a nearby village. Limba was picked and went to Chittor for another round of trials and within days he was on a train to the capital in peak winter. One of the dingy rooms in the concrete labyrinth of the JLN Stadium became his home.

“It was freezing cold and we had to get up early to practice. In my village when it got cold we would light a fire and sit around it. At the stadium it was not possible. There was no hot water. The food was different. I had not trained with the equipment I was using in Delhi. This was a new experience. Back home I used to shoot birds for fun but this was serious stuff. We were being trained to win medals. We were asked to do yoga. I was like a fish out of water. But as the days passed I got used to it. We were provided sweatshirts a month later and it provided relief from the cold. That is when I thought ‘ok I can stay in Delhi’,” he says.

Limba progressed up the ranks quickly and a buzz grew about the prodigious tribal boy. Within months of moving to Delhi, at his first major competition –in the junior nationals in Bangalore – he won gold.

“From Bangalore, we had to travel to Kolkata for a national camp. We had unreserved train tickets. I remember standing near the bathroom of the train compartment all the way from Bangalore to Kolkata. I had to lug my equipment on my shoulder. That is how we traveled back in those days. But I never complained.”

In a couple of years Limba became a double-medallist at the Asia Cup archery. In 1991, he was bestowed with an Arjuna Award winner. One of the perks was a second-AC train pass.

“Overnight I became a VIP. From standing on foot boards and next to smelly toilets suddenly I was travelling like a king.”

The Barcelona Olympic Games a year later was to be his crowning glory , and Limba believed so and the anticipation was frenzied. The sport had been at the pinnacle of its popularity during that edition after the sensational opening ceremony at Barcelona with its archery centrepiece, and despite his failure, the moment would stick in most memories – including that of India’s first individual gold medallist Abhinav Bindra.

History beckoned as Limba’s scores before the Games were better than the Koreans, Chinese and the Spanish – countries which were tipped to win. He was also in the zone — a zen-like state athletes strive for — on reaching the Games village.

However, over-enthusiastic officials ruined his chances. They wanted to celebrate the potential medal a day earlier.

“I was in a deep state of meditation before the event. Archery is such a mental sport and it is vital to find inner calm. If the mind wanders even slightly, you won’t fire the arrow well. I was summoned to meet the officials even as I was meditating. They told me ‘we will carry you on our shoulders and take you to India with the medal around your neck’. I was angry and irritated that I was disturbed. I came back to my room but could not focus again.”

Next day, the three-time Olympian, shot in anger and missed a medal by a whisker.

The first lesson Limba drills into his trainees is not to lose their cool whatever the circumstances. He keeps a close eye on the talent pool at the archery academy in Jagatpura constantly scanning them for the next prodigy.

“I want to find an archer from Saradeet who can emulate me or exceed what I achieved. There is so much talent in the villages but more can be done to identify them. Once my health improves I will travel the length and breadth of the state. If I can train an archer from my village or nearby villages and he or she becomes a star it will be very satisfying. Else my villagers will ask ‘Limba Ram hamare liye kya kiya?”