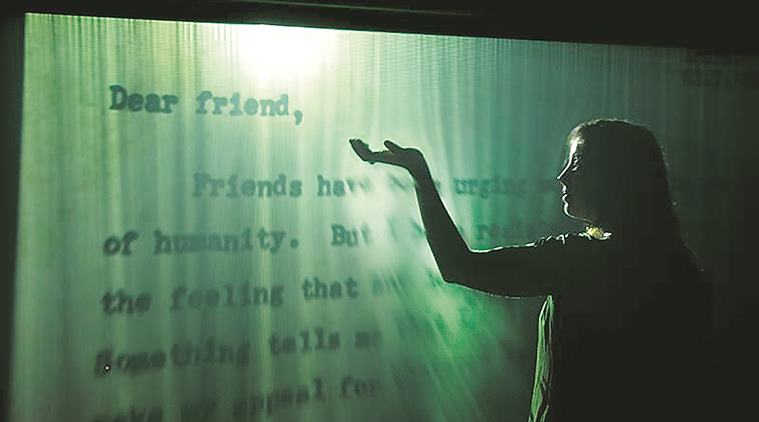

Jitish Kallat’s Covering Letter

Jitish Kallat’s Covering Letter

Jitish Kallat,

artist

I’m deeply inspired by the manner in which Mahatma Gandhi conducted his life in the mode of the open experiment. When one reflects on his life, it appears as both a laboratory and a stage… an expanded arena where experiments with life-energies were undertaken and staged openly even in the most trying conditions. One Gandhian aspect that I feel a deep affinity to is observing the relationship between what one ingests (food, thought and information) and the manner in which it directs one’s moral and creative intuitions.

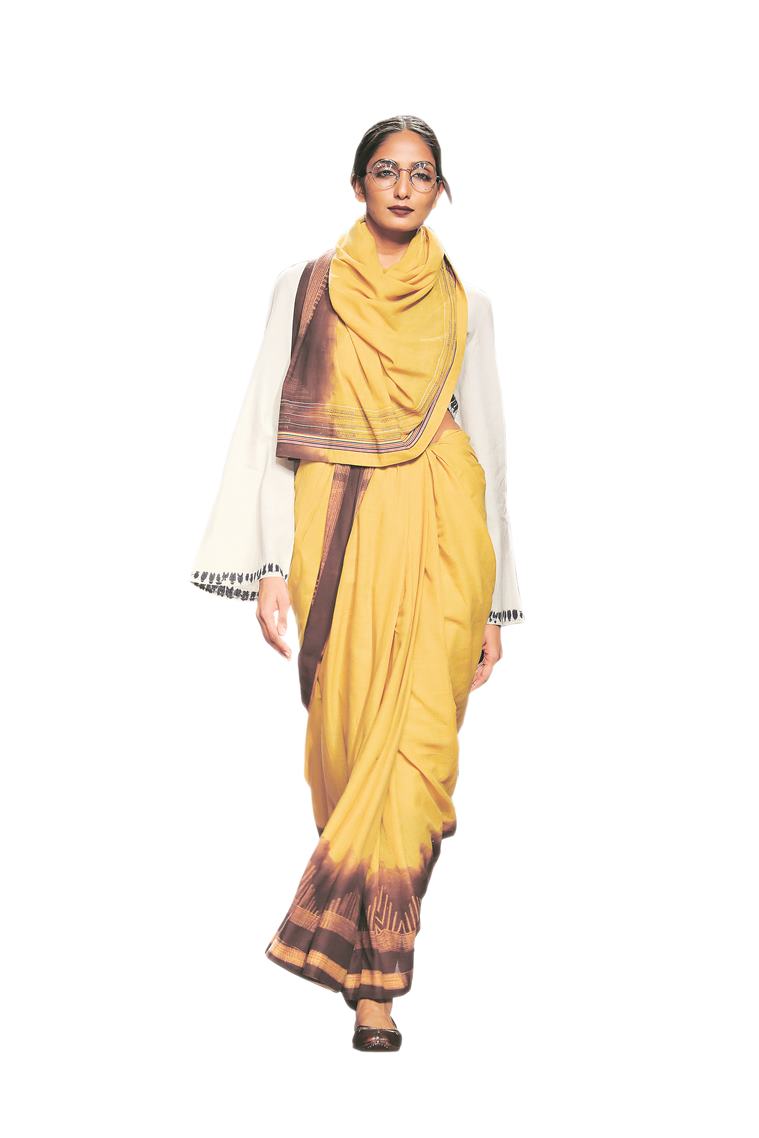

A design by Anju Modi from the “Swadeshi” collection;

A design by Anju Modi from the “Swadeshi” collection;

Anju Modi,

fashion designer

Even when I started working as a designer in 1990, I used to travel to villages in-and-around Andhra Pradesh — including Vijaywada and Venkatgiri — which have many khadi weaving clusters. I think that’s where the fascination with the fabric started. I have subconsciously imbibed the simplicity of khadi in most of my collections — as a way of cultural patriotism, just as Gandhi had envisioned. We are finally realising the potential of this multifaceted fabric. For me, using khadi in my designs is the practical realisation of the Gandhian value system. It’s a homegrown fabric. It’s also about creating economic self-sustainability for our weavers and artisans. I source khadi from across India. Nowadays, I am looking at West Bengal and areas around Hyderabad, where khadi is soft and supple. In my “Draupadi” collection I had used khadi as the core fabric. Couture is all about deep focus and attention to detail, which I think is in abundance where khadi is concerned. The simple act of creating the thread on a spinning wheel and then weaving it on a handloom is very meditative. In 2017, I dedicated an entire pret collection, “Swadeshi’, to the fabric. I even used the round Gandhi spectacles and simple white jhola. I think khadi made a comeback some ten years ago, and it’s here to stay. Gandhian values are also being revisited.

Anubhav Sinha,

film director

Currently, I’m reading My Experiments with Truth for the first time. The most important aspect of his life, for me, is that he always did the right thing. What I love about him is that he was an idealist, but also smart. He could negotiate with people and situations. He always spoke the truth — whether it is about going to a brothel, eating non-vegetarian food, his complexes while living in London, or not being able to do well as a lawyer. He made mistakes but he was a work-in-progress man all the time. He had all the shortcomings of a common man but he overcame them. That’s what made him a Mahatma. He had a good business sense. More often than not, he was successful in his negotiations with the British. He was leading a revolution but was trying to do the right thing in the most

non-violent manner.

Riyas Komu’s Dhamma Swaraj

Riyas Komu’s Dhamma Swaraj

Riyas Komu,

artist, co-founder of Kochi-Muziris Biennale

In the present times of unbridled surveillance, I am really interested in understanding the idea of equality. It becomes even more relevant when we hear arguments around freedom of expression, identity, multiculturalism, coexistence, diversity, and constitutional values. We need to redefine the concept of equality in the present socio-political context. In my recent work On International Workers’ Day, Gandhi from Kochi, I juxtaposed Swaraj with the idea of control. Today, Gandhi would have fought against surveillance of the state to suppress the idea of equality. Gandhi with his transformative principles would have addressed how to fight fear in the social space, resist violence and victimisation… I don’t claim to abide by any particular Gandhian principles because Gandhi himself would warn against such clauses. He urges people to experiment with the truth. It is time to talk about ‘Dhamma Swaraj’ (equality). We need to look at Dr BR Ambedkar as a countersignature to the Gandhi’s political imagination. The two need to co-exist to fight for equality, since Ambedkar’s fundamental concept bears ‘equality’ as a signature of his thought praxis, and especially today, in the conflicting times there is a need to work on this concept. In fact, Lion Capital, the national emblem, articulates ‘Dhamma Swaraj’ — it’s a symbol taken from the Buddhist imagination of the senses of life looking in four different directions, propagating dhamma, idea of co-existence. At the bottom, we have a Gandhian signature, Satyamev Jayate, taken from the Upanishads. Finally, we need to work on Ambedkar’s axiomatic concept of equality, without which any experiment with the truth may not find its way to its beginning point. The new experiments with truth cannot begin without the idea and thought of equality.

Parvez Akhtar,

theatre director

Mahatma Gandhi’s sense of commitment is what deeply attracts me. Whoever wants to change society for the better or struggle against an evil must become a leader with commitment. Gandhiji thought that cowardice was the greatest evil in humanity. If you believe in something, you should say it truthfully, without fearing a backlash. I have tried to show these traits in my play, Bapu, which has been staged across India in the last 18 months.

A canvas from Haku Shah’s “Nitya Gandhi” series

A canvas from Haku Shah’s “Nitya Gandhi” series

Vidya Shah,

vocalist

Vaishanav jan toh taine kahiye, peed parayi jaane hai (Call those people vaishnavas, who feel the pain of others). This 15th-century bhajan by poet Narsinh Mehta remains memorable for me. Not only because one has heard it since childhood and we all hum the MS Subbulakshmi version — in raag Desh — but also because I sang it at Sabarmati Ashram in the relatively unpopular style, the way it was sung for Gandhiji, as a prayer. It was in October 2014, as part of a concert at the opening of my father-in-law, Hakku Shah’s painting exhibition titled “Nitya Gandhi”. The evocative title draws your attention to the idea that Gandhi’s philosophy can be the way to live — in today’s times we are trying to hang onto values like simple living, honesty, truth and self-sufficiency. In the bhajan itself, there are so many ideas that are significant. It says, Para duhkhe upakara kare to ye, mana abhimana ana ne re (Help those who are in misery, but never let self-conceit enter their mind). Now, that’s a very tall order in today’s times. Then there is the nirgun (without form) aspect. It’s not a nirgun bhajan but the nirgun aspect of it is significant. These are all ideas central to Hindu philosophy and Gandhiji was probably drawn to this bhajan because it is one of the few pieces that has managed to encapsulate most of his beliefs and principles.